Las Vegas woman’s donation of son’s corneas leaves her angry

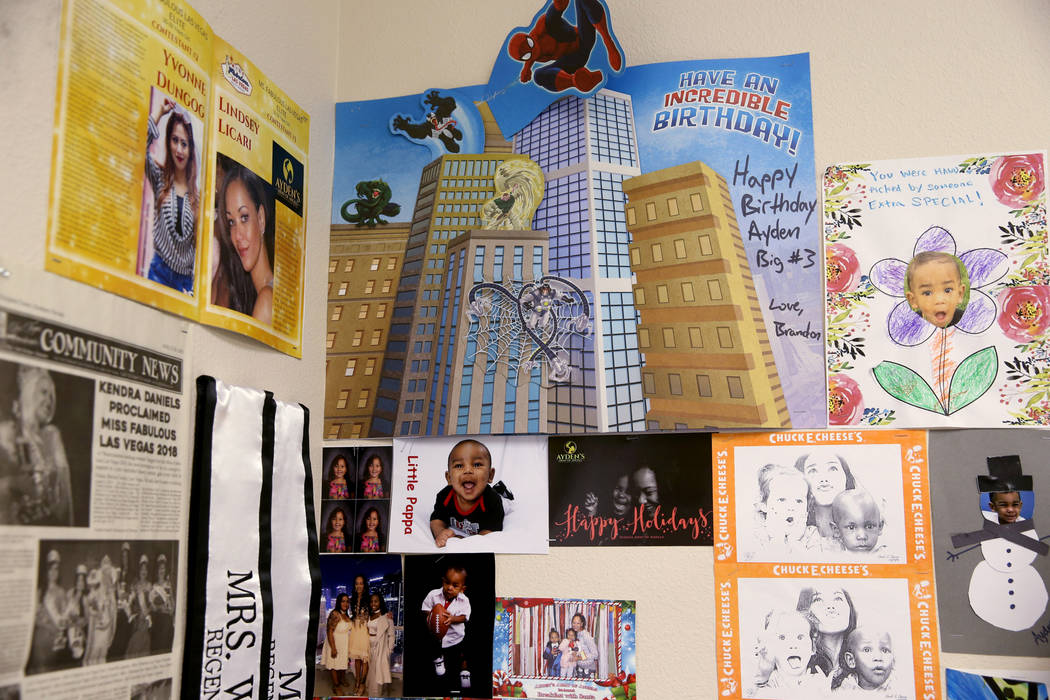

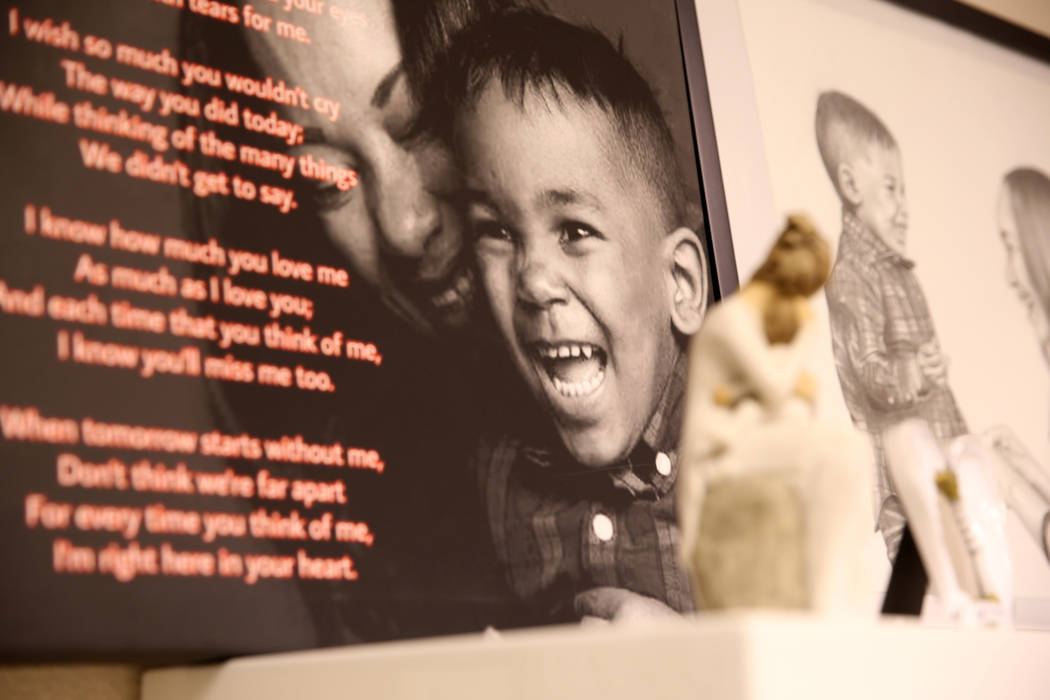

Since her 3-year-old son, Ayden, died two years ago of cancer of the muscle tissue, Lindsey LiCari has found her life’s purpose in making something good come out of his death.

Among other things, the Las Vegas resident agreed to donate his corneas so that, she thought, another child in the U.S. would receive the gift of sight. Last week, she even shared on Instagram a post by the Nevada Donor Network that featured a photo of her son and encouraged organ and tissue donation.

But when she learned from a network representative in an exchange following the post that her son’s corneas had been sent overseas, her pain was too raw for her to remain silent.

“I would love to know how much money you guys got for my son’s corneas that I gave to you guys — for free — to help a kid in the United States — for free,” she asked in a video posted on Instagram last week. LiCari, who started a foundation to assist children with cancer or sickle cell anemia and their families, has 316,000 Instagram followers.

In an interview with the Review-Journal, LiCari acknowledged that she did not read the authorization form in the hours after her son’s death. But she said she was assured by Nevada Donor Network staff that her son’s corneas could go to one or more children and that she could meet a recipient unless the recipient did not wish to do so. It never ever occurred to her that her son’s corneas could be sent to another country.

“I will never get that opportunity to look into the eyes of whoever got my son,” she said. “To me, his eyes were the most beautiful part of him. They would dig into your soul.”

LiCari’s experience illustrates the confusion that can surround tissue-donation authorization, which comes at a time when families are overwhelmed by grief and communication may be less than crystal clear.

Supply outstrips U.S. demand

What LiCari didn’t know, and says she wasn’t told, was that there are enough donated corneas in the U.S. to meet the need here, so a substantial number are sent to recipients in other countries.

In 2018, U.S. eye banks provided more than 51,000 corneas for domestic transplants, while almost 28,000 corneas — or about 35 percent of the total — were placed internationally, said Kevin Corcoran, president and CEO of the Eye Bank Association of America.

“While we’re fortunate to fulfill 100 percent of our domestic need, without waiting lists or delays, no other country has as effective a donation and transplantation system as the U.S.,” Corcoran said in an email. “Globally, there are approximately 10 million cornea-blind or visually-impaired individuals, so (LiCari’s) son helped transform two lives somewhere in the world.”

The Nevada Donor Network said in a statement that it completes an authorization over a recorded phone line, and that “the option is given to families to determine whether or not they consent to international donation.”

But LiCari said a network representative approached her at the hospital as her son’s body was about to be taken away.

“I said goodbye to my son, and he took his last breath, and I held him,” LiCari recalled. “I held him for hours. My family came into the room, and another person came into the room. And I didn’t really understand why she was there.

“… Once Ayden started getting cold, I had to give him to the morgue. The lady then pulled me aside, asked me about giving the gift of sight and donating Ayden’s corneas. I thought of Ayden and I knew Ayden was here for a purpose — God sent him special. Ayden was a person who would give freely all the time.

“If I was another mother, I’d want my child to get corneas, to have the gift of sight. I saw the beauty in giving sight to two other children through my son,” said LiCari, whose foundation, Ayden’s Army of Angels, provides nutritional, financial and other support to young cancer and sickle-cell patients and their families.

LiCari fears that because her son’s corneas were sent to another country, they were sold for a profit.

“There’s no way that any other country is getting something like this from the United States for free,” she said.

But the Nevada Donor Network said that it abides by all state and federal laws, including the National Organ Transplant Act, which makes it illegal to sell human organs and tissues. But cost-based reimbursement from transplant hospitals and tissue processors “provides funding to continue our mission,” it said.

The statement continued, “When tissue is placed internationally, Nevada Donor Network is reimbursed at a lower rate than if the tissue is placed for transplant in the the U.S. In an effort to maximize donation, we maintain domestic and international partnerships, which allow as many gifts as possible to be transplanted.”

LiCari said that her repeated requests to the Nevada Donor Network for information about the recipient of Ayden’s corneas went unheeded until last week. The network since has offered to facilitate an exchange of letters between her and the recipient, but could not immediately tell her in what country that person lived.

Loss of accreditation

In June, the Nevada Donor Network’s eye bank lost its accreditation to process and distribute eye tissue. The network, which facilitates cornea donation statewide, said it detected “process gaps” in April and suspended its eye bank operations. It has applied for reaccreditation from the eye bank association and plans to resume operations under new leadership.

Laura Siminoff, dean of the College of Health at Temple University, said succinct, clear verbal communication with families is critical at the time of donation authorization, especially considering that most are under too much stress to read the authorization form.

On a national scale, there has been a problem for years in what families are told regarding tissue donation, said Siminoff, who has researched the topic. Some tissue banks are not ensuring that families truly understand what they are donating and how the process works.

She attributes this shortcoming to a “failure of the FDA (the Food and Drug Administration) to regulate in a clear way.”

A spokeswoman for the FDA said that the agency’s regulation of tissues focuses not on communication but on limiting the risk of transmission of disease, minimizing the risk of contamination and requiring demonstration of safety and effectiveness.

Siminoff cited the National Kidney Foundation’s informed-consent policy for tissue donation as the gold standard. Among its tenets, it states that “families must be told that they have the right to limit or restrict the use of the tissue.”

The Eye Bank Association “encourages our members to provide as much information as possible to donor family members,” Corcoran said. “Given the circumstances of these conversations (soon after the death of a loved one), family members sometimes forget or misremember some aspects of the information that has been shared with them.”

But Siminoff said, “Everyone would be done a favor by having clear guidelines that organizations have to adhere to.”

The families of organ donors, she said, “(have) made a decision to make a donation, and it’s a generous decision. And we should make sure they’re happy with the decision, that they feel good about the decision.

“For me, that’s the ethical thing.”

Contact Mary Hynes at mhynes@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0336. Follow @MaryHynes1 on Twitter.