Las Vegas won’t cash in on Allegiant Stadium, convention center just yet

There it stands, a dark harbinger of bright hopes.

Gleaming black as if chiseled from onyx, Allegiant Stadium doubles as a state-of-the-art sports and events complex and a symbol of an aspirational city’s grandest aspirations yet, projected to draw 450,000 visitors annually while pumping $620 million into the local economy and creating nearly 6,000 jobs.

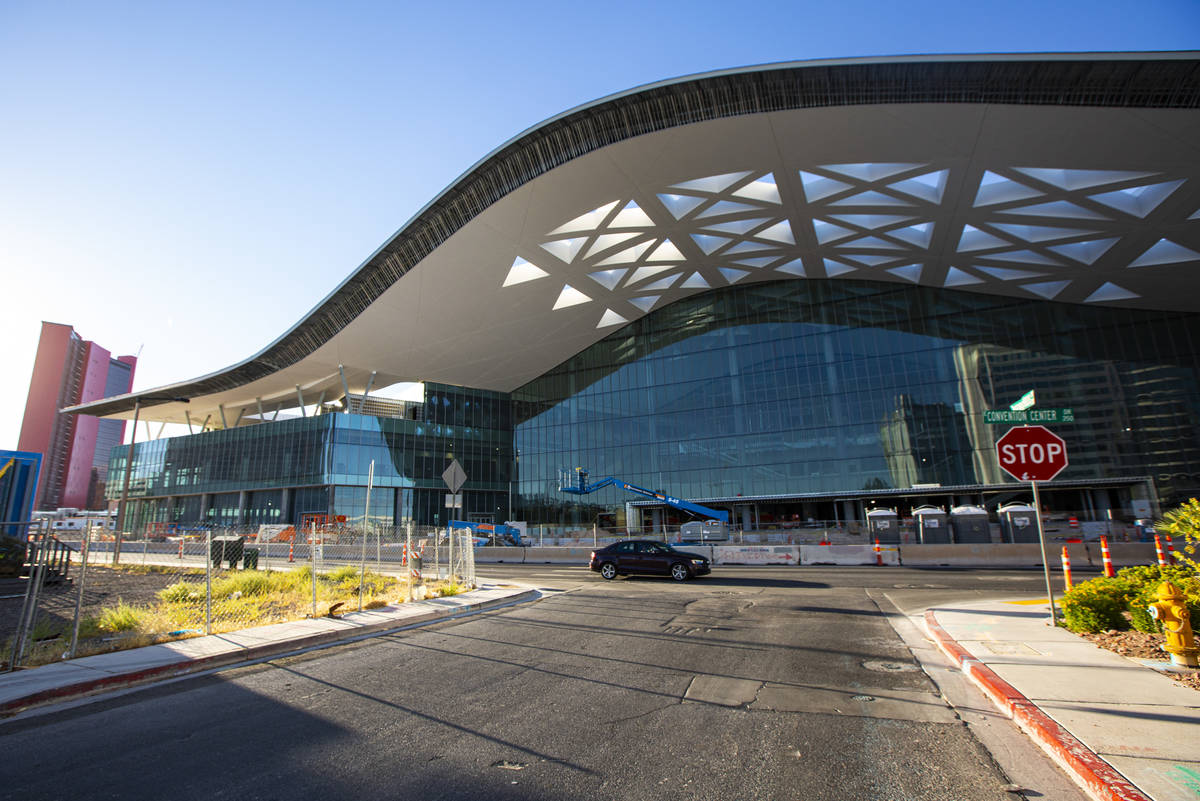

A mile up the road sprawls another high-tech testament to a destination city’s draw, the mammoth Las Vegas Convention Center, which has grown larger still with a 1.4 million-square-foot expansion project originally set to be unveiled in January at CES, one of North America’s largest conventions.

Both required substantial taxpayer contributions via hotel room tax increases: $750 million of Allegiant Stadium’s $2 billion price tag; the majority of the Convention Center additions’ $1.4 billion cost.

And both currently sit empty and are likely to remain that way for the immediate future: Because of coronavirus concerns, CES announced Tuesday that it would go fully online in 2021, negating the 175,000 expected attendees and the $300 million they would have infused into the city; a day later, Garth Brooks postponed his Aug. 22 concert at Allegiant Stadium to February 2021, foreshadowing an upcoming NFL season where there probably will be no fans in the stands when the Las Vegas Raiders make their debut in September.

Now, there will be no immediate return on these massive public investments with Las Vegas seeing little after spending a lot.

“We’re just going to have to tighten our belts,” Clark County Commissioner Tick Segerblom says. “At some point this is going to be over and we can get back to normal. But it looks like for the next six months to a year our visitor volume and our large events like CES or the stadium are just not going to happen.”

In other words, Vegas won’t be cashing in on these cash cows just yet.

“You build these kinds of projects for 30, 40, 50 years, and most all of those 40 and 50 years are going to be great years and these projects are going to be a catalyst for Las Vegas’ recovery,” says Steve Hill, chairman of the Las Vegas Stadium Authority and president and CEO of the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority. “But certainly it is disappointing and harmful to people who would’ve been able to work there and would have been able to work elsewhere because of these projects. But it’s the situation we’re in.”

How we got here

Before shovels hit ground, pens hit paper.

Planning for the stadium and the Las Vegas Convention Center expansion began five years ago, when then-Gov. Brian Sandoval issued an executive order July 6, 2015, establishing the Southern Nevada Tourism Infrastructure Committee to study how new investments could help the state capitalize on the tourism economy.

The stadium and Convention Center expansion were among several ideas percolating around the committee. Headed by Hill, then director of the Governor’s Office of Economic Development, the committee met 16 times to consider what kind of infrastructure would best benefit Southern Nevada.

It didn’t take long for a stadium proposal and the Convention Center expansion to reach the top of the list.

A development team consisting of the Las Vegas Sands Corp., Majestic Realty and the Oakland Raiders proposed a public-private partnership to build a 65,000-seat, NFL-ready indoor stadium in Southern Nevada. Sands Chairman Sheldon Adelson pledged $650 million from his family for the project.

For committee members, the stadium checked three boxes: It added a state-of-the-art stadium for concerts and special events, it provided a place for the UNLV football team to play, and it jump-started the Southern Nevada economy with new jobs.

While many residents were supportive of the stadium idea, there still was opposition because of the proposed investment of $750 million in public funds, the largest amount of public money devoted to a public-private stadium project.

One such critic was Segerblom, then a Nevada state senator, who initially opposed the proposal before later embracing the idea.

“My biggest concern, first off, was that we committed that much tax money when we have other needs,” he says. “But the other thing is to partner with somebody who’s going to benefit from taxpayer dollars for a billionaire when we could have just built the thing ourselves and it would have been a public stadium.”

A key strategic move was the placement of the Convention Center expansion proposal in the same bill as the stadium financing. The public was far more supportive of the Convention Center project because of the need to keep up with convention industry competitors in other cities.

When the special legislative session convened in October 2016, lawmakers spent four days debating the merits of Senate Bill 1, which imposed a 0.88 percent room tax increase on most properties within the resort corridor to help fund the stadium.

The legislation was narrowly approved by the Senate and Assembly and signed into law by Sandoval on Oct. 17.

But the drama wasn’t over.

In January 2017, Adelson withdrew his financial commitment, and the team obtained $650 million in financing from Bank of America. The NFL still had to sign off on the Raiders relocating to Las Vegas, and that vote turned out to be more lopsided than most expected with team owners voting 31-1 in March 2017 to back the move.

The Convention Center’s $1.4 billion expansion had a much easier path.

Senate Bill 1 also included 0.5 percent increase in the hotel room tax to pay off bonds involved in building the $980.3 million West Hall expansion and a $52.5 million underground people-mover designed by Elon Musk and The Boring Company.

There was little opposition to the Convention Center project. The future was now.

Looking ahead

With $16 billion in revenue in 2019, the NFL is the alpha silverback male gorilla of professional sports in the United States.

The majority of that revenue comes from TV deals, meaning that while having no fans in the stands will surely mean a substantial hit for teams this year, it won’t be a crippling blow.

In 2018, the last year for which statistics are available, the Raiders — playing in their previous home of Oakland, California — ranked last in the league with stadium revenues of $77 million out of a total $357 million in earnings.

Surely the former number will increase substantially in a luxe new facility like Allegiant Stadium, but broadcast rights will still provide significant income regardless.

With the NFL’s rabid fans and immense popularity, it seems safe to say that the league will weather the coronavirus, protecting the investment in Allegiant Stadium, which will benefit from other events as well.

“From the stadium’s perspective, sports fans around the country and around the globe can’t wait to get back to sporting events and concerts and everything that will happen at the stadium,” Hill says. “Those things, I think, will recover as soon as the health situation recovers. It’s one of the big reasons I said that the stadium is going to be a big part of the recovery of Las Vegas because as soon as you can fill the stadium, you’re going to fill the stadium. I don’t think there’s any question about that.”

As for CES and other conventions, the picture isn’t quite as clear.

“The real question is going to be the convention business, whether going online, virtual, somehow changes that dynamic because we have really built the future of Las Vegas on conventions,” Segerblom notes.

Hill acknowledges these concerns as well.

“There’s been a lot of conversation about meetings and conventions and what that whole industry will learn from doing things remotely and virtually, and I think it will add some level of change of how people think about meetings and conventions,” he says. “I think it’s an opportunity for Las Vegas, but I also think it’s important to point out that there are a lot of shows and meetings that want to be in Las Vegas because Vegas is still the place that people want to have those events.”

Jeremy Aguero, principal for Las Vegas-based Applied Analysis, said the economic rebound from the Convention Center expansion and the stadium would be similar to what occurred with development of the $2.4 billion Terminal 3 at McCarran International Airport. The project was planned in 2005, and construction began in June 2007, just months before the Great Recession began.

“I got chewed out on more than one occasion about how that project should never be going forward,” Aguero said of the 14-gate terminal, which opened in 2012. “It was too expensive. Las Vegas wasn’t going to come back. Las Vegas was building into a recession. All those types of things.

“It took a remarkable amount of political courage to get that project completed. We never would have recovered the way that we did but for T3,” he said. “I really believe the same thing is true with the Convention Center expansion and the stadium.”

And so whether it’s the stadium or the Convention Center, both projects’ long-term prospects have the same built-in advantage: the city they call home.

“There’s going to be a need for convention space, for large gatherings, and there’s no place better than Las Vegas — and there never will be,” Segerblom says. “We’re just built for this.”

The Review-Journal is owned by the family of Las Vegas Sands Corp. Chairman and CEO Sheldon Adelson.

Related

Raider riding: A journey down the Strip to Allegiant Stadium