Hank Aaron left his mark on Atlanta — even with old Falcons

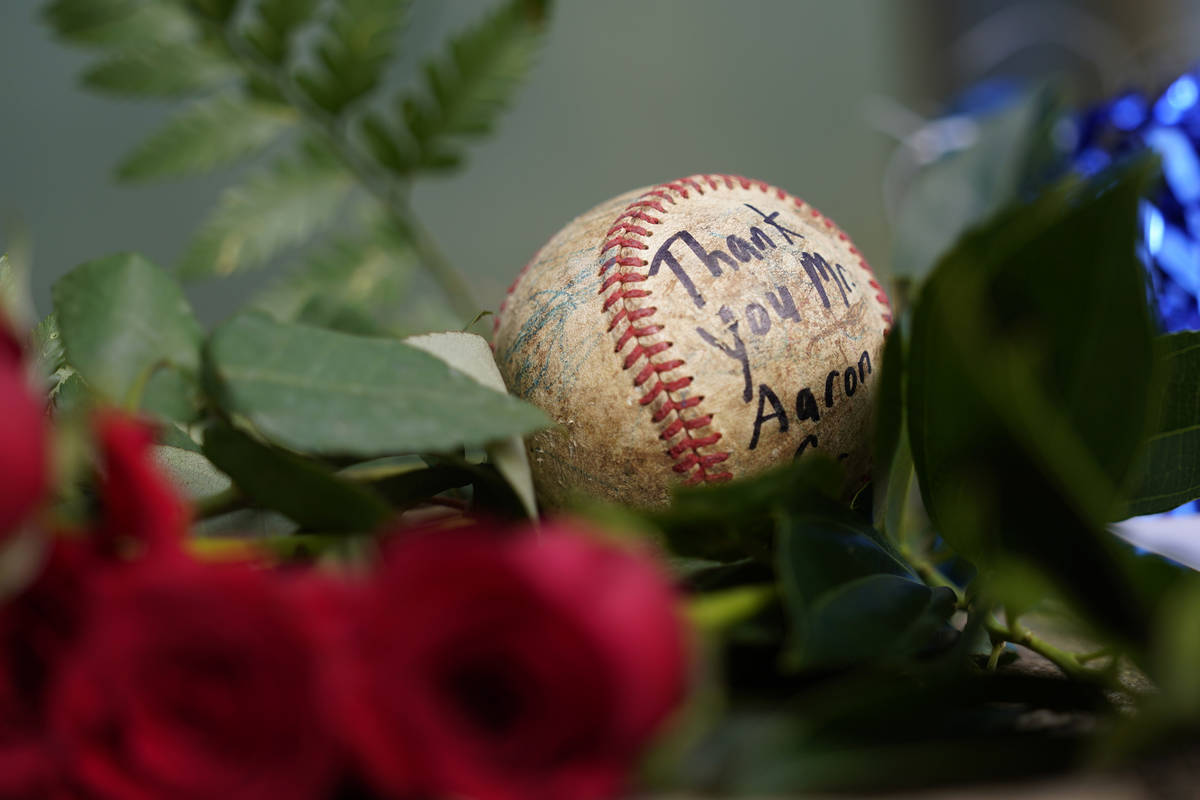

When word got out that Hank Aaron had died Friday, George Kunz left a message on my voicemail. The former All-Pro offensive tackle was seeking confirmation that the grim news was true.

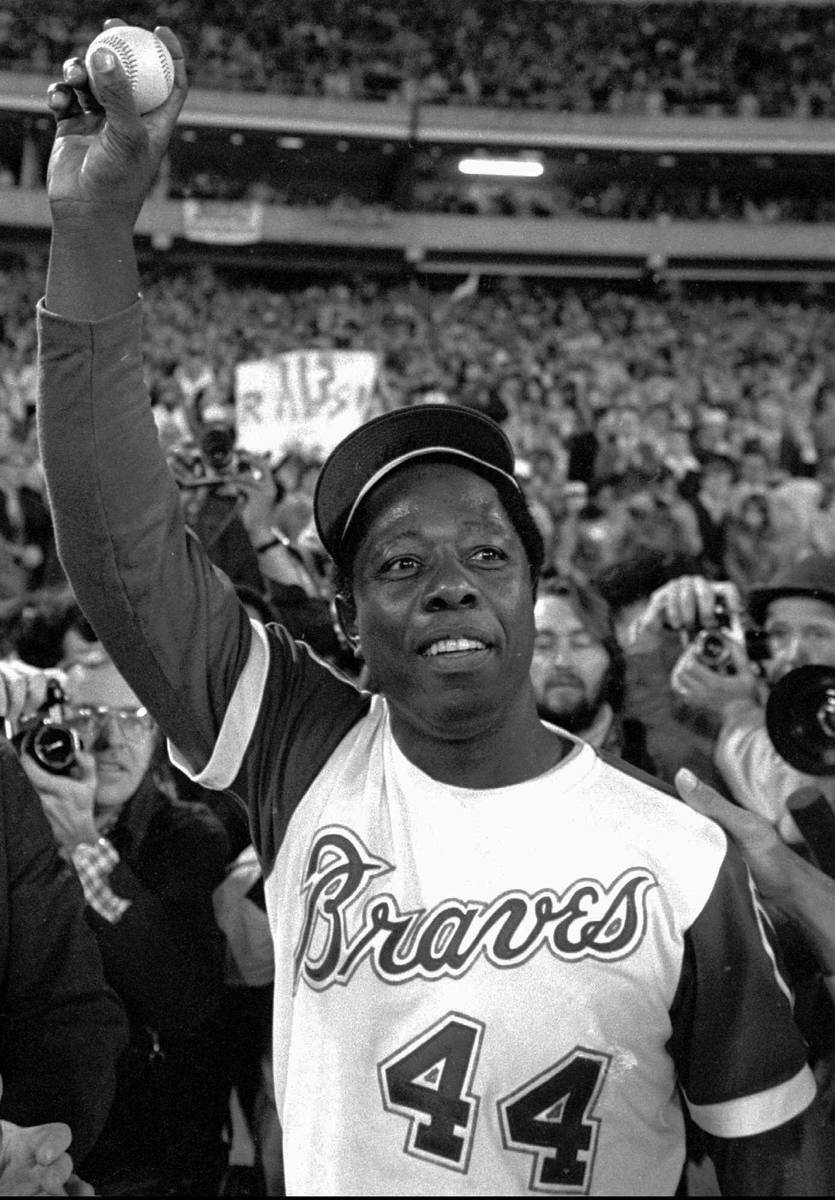

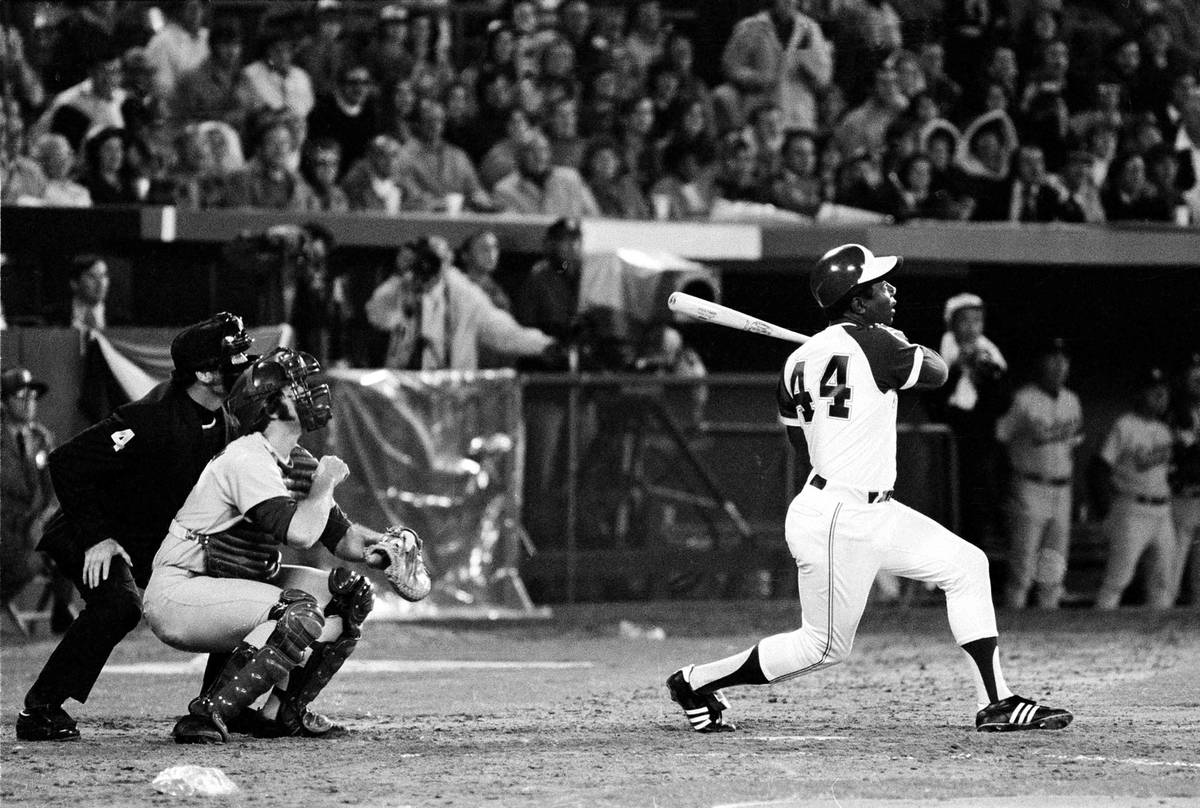

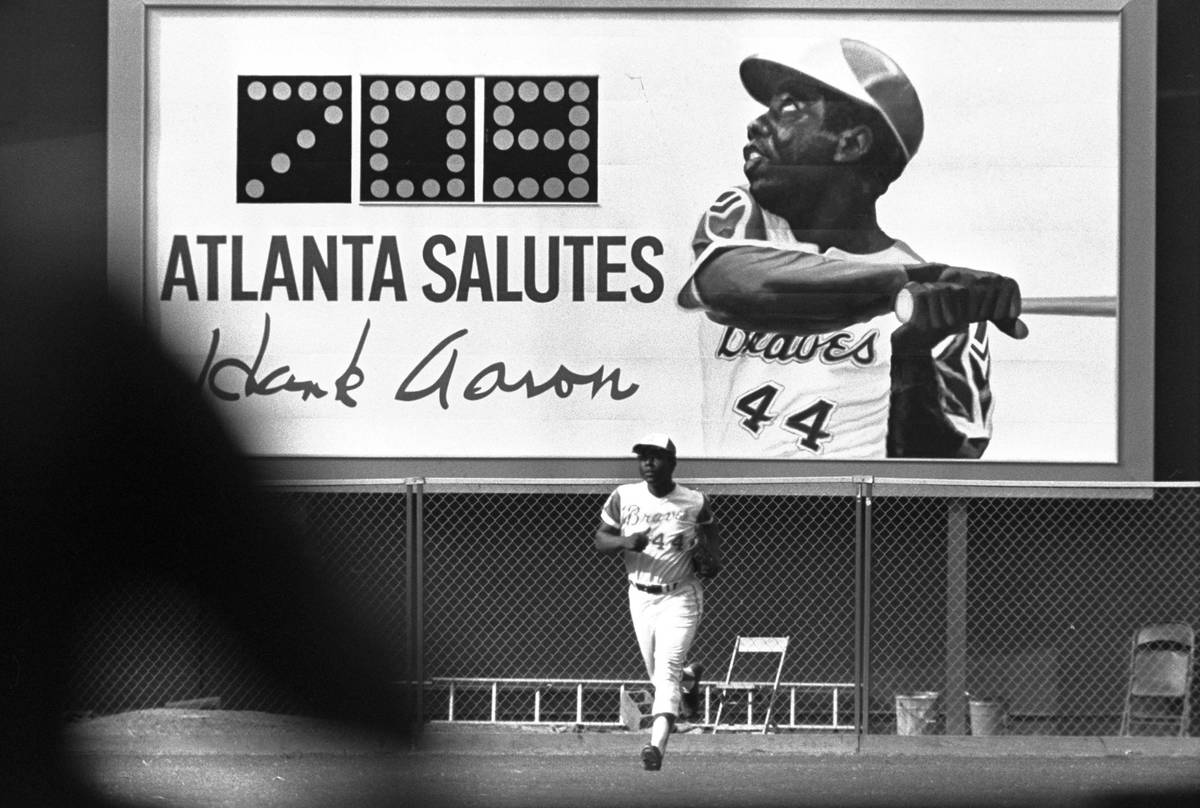

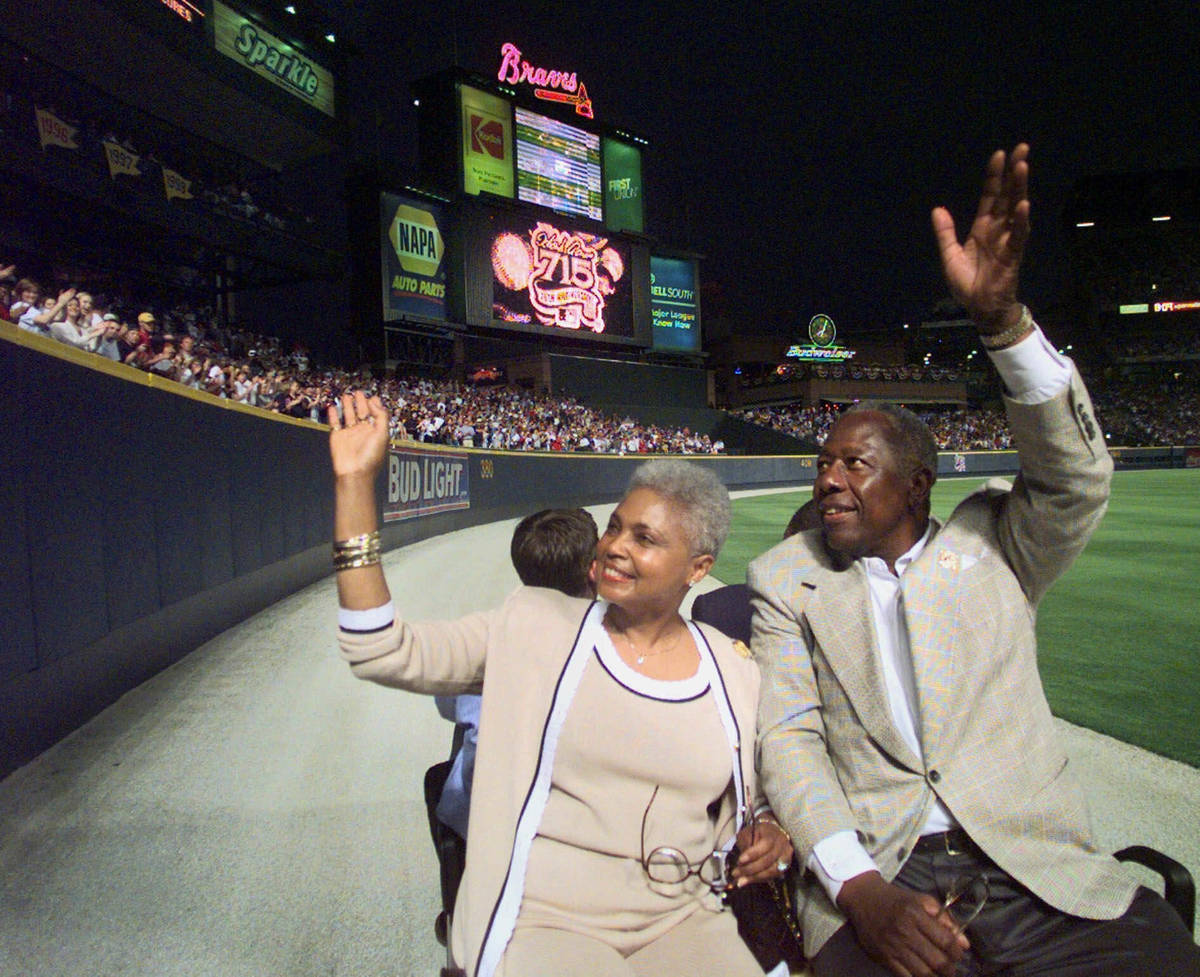

Most baseball fans of a certain age still recall where they were and what they were doing when Aaron smacked No. 715 off Al Downing to surpass Babe Ruth’s career home run total. How when others targeted him with the racists taunts and threats, he bravely persevered.

But Kunz mostly wanted to talk about his warning track power.

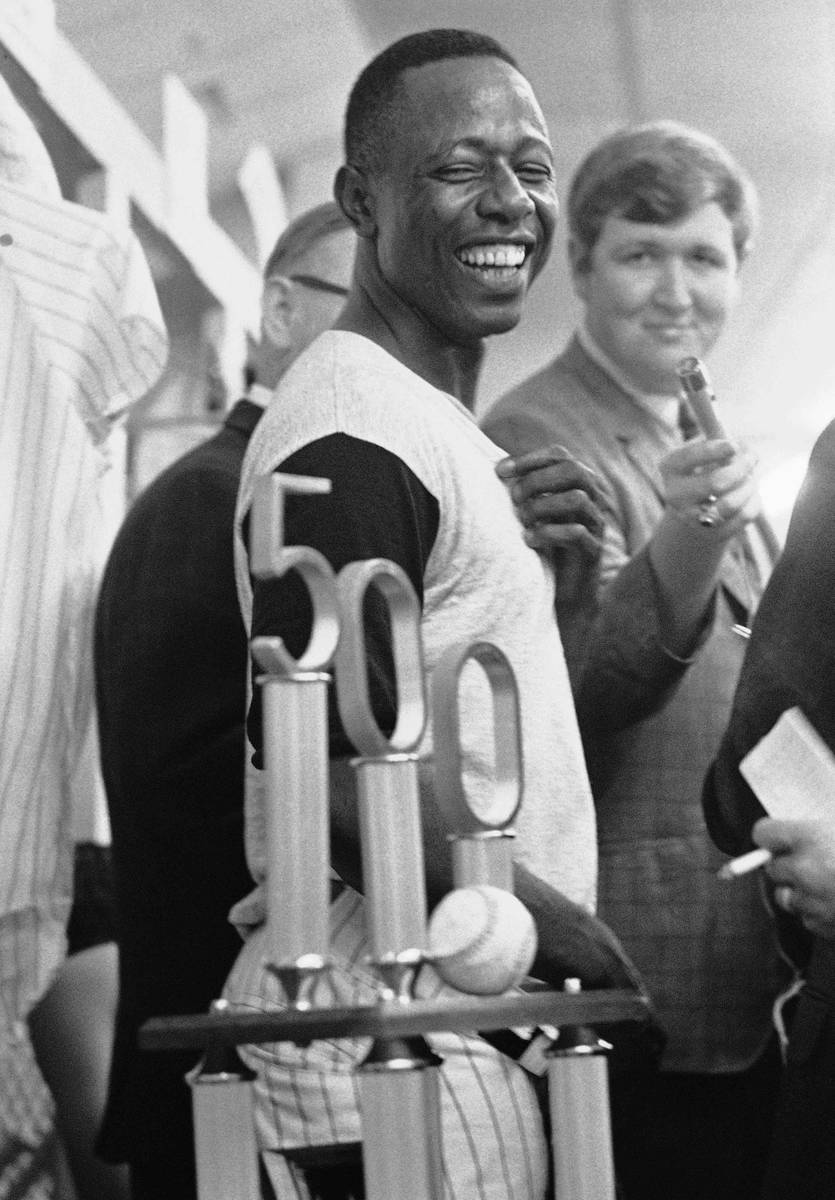

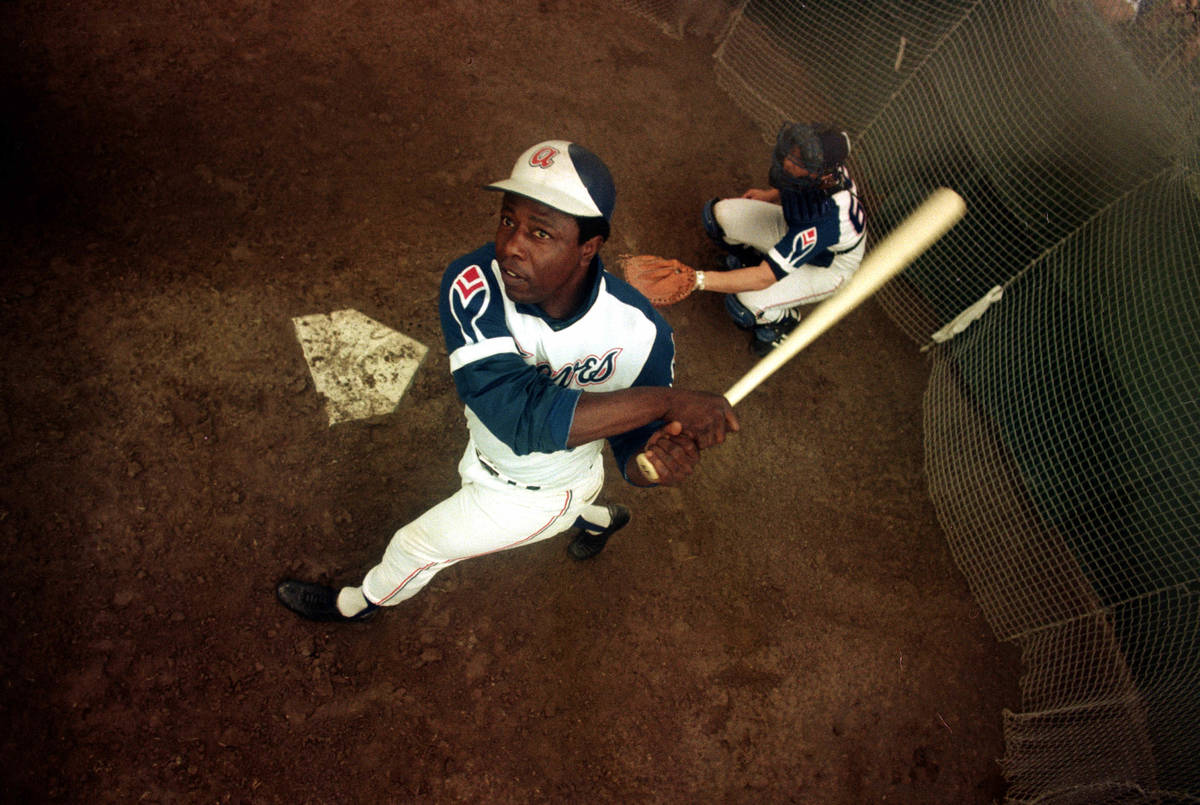

That’s a description rarely used in conjunction with the kind and decent slugger who during 23 illustrious major league seasons walloped 755 baseballs that cleared the warning track and landed in distant bleachers, bullpens and, after the Braves moved from Milwaukee to Atlanta, a since eliminated mascot’s teepee.

So perhaps it is best to let Kunz explain:

“When I was drafted by Atlanta (second overall in 1969 after O.J. Simpson was selected first by Buffalo) we had the Coaches All-American Game in Atlanta, at old Fulton County Stadium,” recalled the longtime Las Vegan and former bulwark of the Falcons’ offensive line under coach Norm Van Brockin.

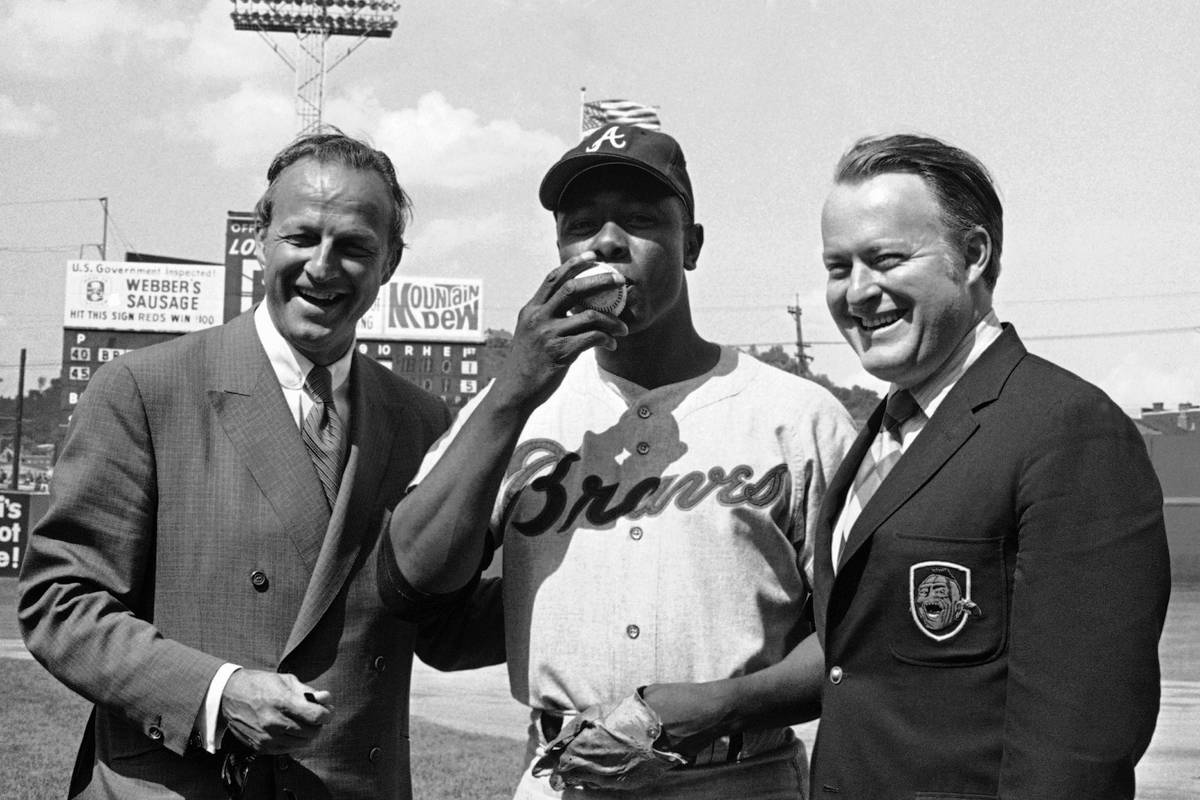

“The Coaches All-American Game game was in the middle of the baseball season, so the Braves arranged for the All-Americans to be paired with a member of their club. They would stand in front of the outfield wall and you could get their autographs.

“I was paired with Hank Aaron.”

Atlanta icons

All-Americans who had starred at less-heralded schools such as Indiana, New Mexico State and The Citadel were paired with baseball equivalents such as Gary Neibauer, Walt Hriniak and Gil Garrido. But as the Falcons’ top draft pick from Notre Dame, Kunz was chosen to partner Hammerin’ Hank himself.

As more than one baseball announcer in those days was fond of exalting, “Holy cow!”

Kunz said Aaron could not have been been more gracious.

“My wife was there, too (Mary Sue Kunz was the queen of that year’s college all-star game before she and George were married), and I’ve got a picture of us near the outfield fence, with Hank in his Braves’ uniform and me in an all-star uniform,” he said.

That photo remains one of his prized possessions.

“I’ve known Hank a long time, and I wish I could say we were great friends,” Kunz said before sharing another anecdote suggesting they might have been closer friends than the football star lets on.

Riding with the Hammer

Kunz said he once was walking Atlanta streets when a guy driving a sporty two-seat Mercedes Benz began to wave and honk his horn.

“So I go over and it’s Hank. ‘C’mon, get in the car.’ We went out and had lunch and had a great conversation. He was kind enough to remember me from that football event.”

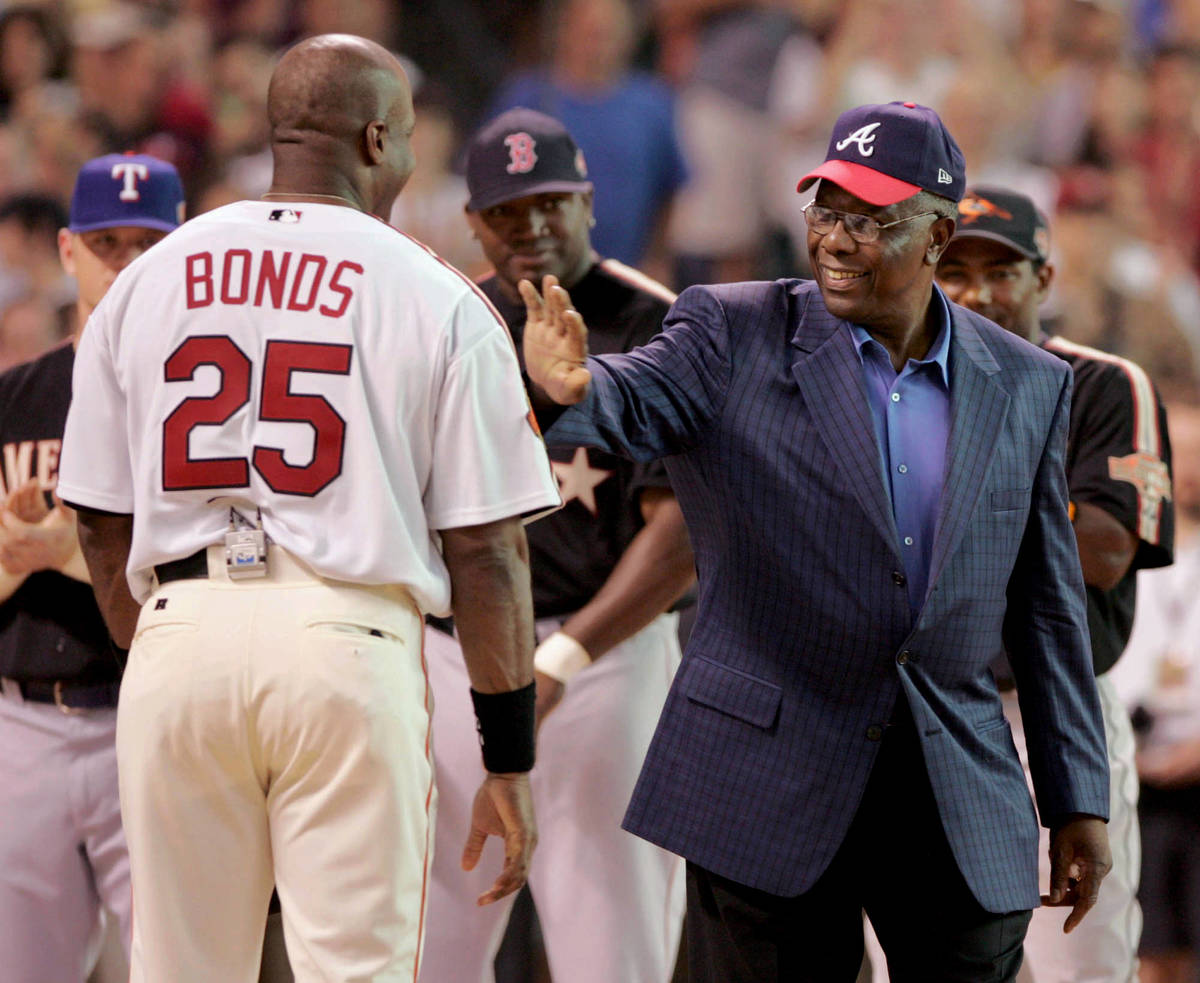

Aaron was a five-tool player before the term existed. But when you add in class, grace, dignity and fellowship, there weren’t enough tools in the box to describe the baseball home run king, Kunz said. Hammerin’ Hank had it all. Including gobs and gobs of warning track power.

“The way he treated the fans when they came to ask for his autograph — and the way they looked at him when we were signing — was something I’ll never forget.”

Kunz would go to become one of the best offensive linemen of his era. He played in the Pro Bowl eight times, including five of his six seasons in Atlanta.

But when they met, Hank Aaron was Hammerin’ Hank, one of the most feared hitters baseball has ever known. And George Kunz was just another big kid with stars in his eyes, and on the broad shoulders of his generic college all-star jersey.

“You couldn’t imagine a more wonderful gentleman who also was an athlete. He was a class guy.”

Contact Ron Kantowski at rkantowski@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0352. Follow @ronkantowski on Twitter.