Young students return to Las Vegas public schools

To prepare her students to return to the classroom on Monday, special education teacher Krista Gies taught them a jingle:

“My nose is covered, my mouth is covered and my hands are off my face,” she sang.

Her class has been practicing wearing masks during virtual lessons since early February — a necessity, Gies said, for her young students who may need extra repetition to master the skill.

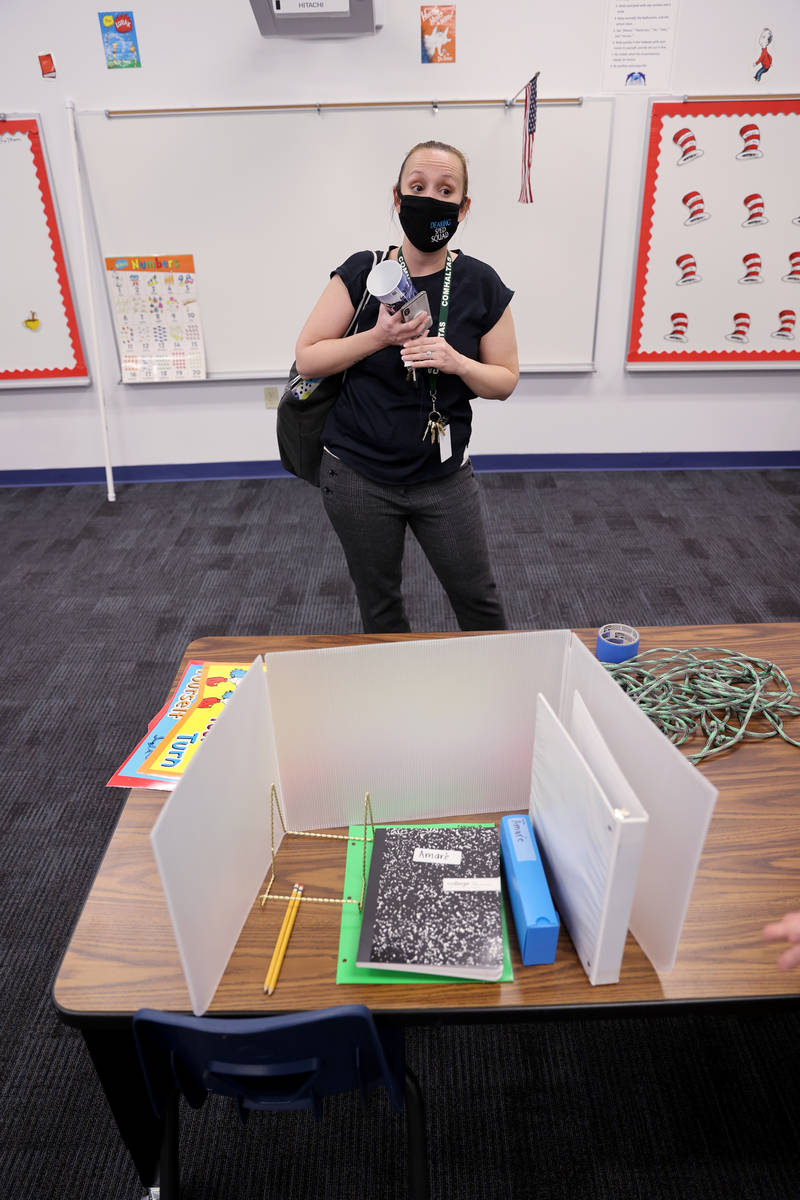

As she prepared her Dearing Elementary School classroom last week for Monday’s return, she checked the view from each desk to make sure students could see over the plastic partitions that separate them from their neighbors. And she prepared a rope with knots spaced 6 feet apart to help the kids walk in a socially distanced line to lunch, which will be consumed outdoors on the blacktop.

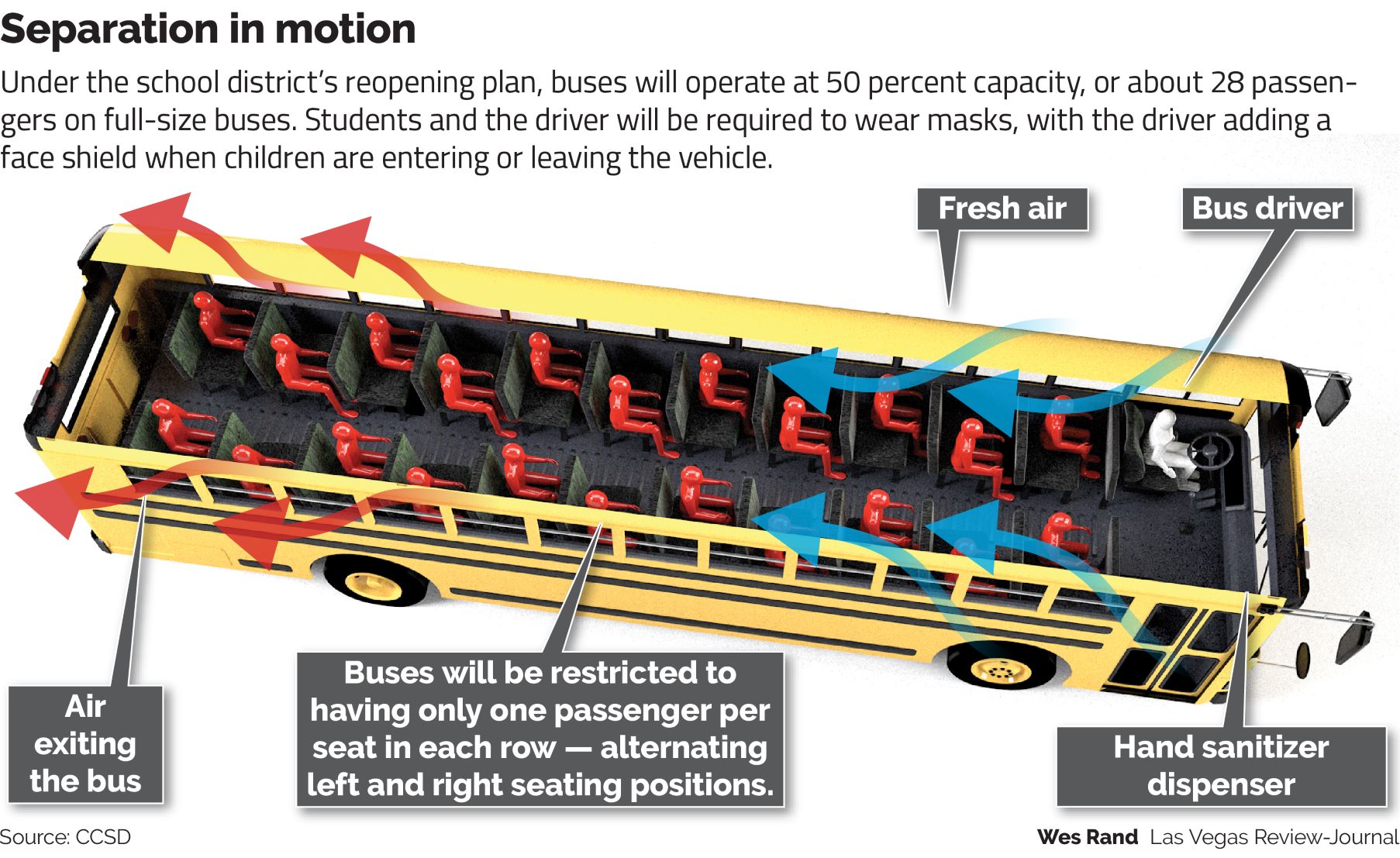

These are just a few of the final touches that elementary teachers and staff across the Clark County School District have been putting on the district’s broad plan to reopen schools to students in preschool through third grade for hybrid instruction, which will see just over 40,000 students returning to 225 schools.

Many of their preparations will need to change in five weeks after the district announced on Wednesday that it will welcome all elementary grades back to campuses full-time on April 6. Older students will return under the hybrid model in two waves beginning March 22.

Surveying her classroom with that announcement in mind, Gies mentioned the spaced-out seating arrangements that would need adjusting to fit all 16 of her students in the classroom.

More changes lie ahead

There probably will be other changes needed too at the east Las Vegas school, which is preparing to bring in 200 students under the hybrid cohort model but typically hosts over 800.

For the immediate future, Assistant Principal Golda Gilliam said the focus is on creating a welcoming space for the students who return to campus on Monday for the first time in nearly a year — some for the first time.

“We’ll cross that bridge when we come to it,” she said of the changes that will occur early next month.

The question of when Clark County schools would reopen has been top of mind almost since March 15, the day they were shut down by an order from Gov. Steve Sisolak.

The district spent the final half of the 2020 spring semester operating under a widely criticized distance learning model, promising to make changes to engage more students in time for the fall semester.

Reopening proposals were weighed and delayed throughout the fall as Nevada weathered a spike in COVID-19 transmission, but the pressure to reopen began to grow over the winter as the district reported significant academic and emotional impacts to students in isolation.

A limited reopening for the youngest students was announced in late January, with older students allowed to come back under a voluntary, small-group model that was eventually scrapped in favor of the plan announced Wednesday.

The timing of the grand April reopening puts CCSD in the bottom half of the pack in comparison to other districts, said UNLV professor Bradley Marianno, who has studied national school closures during the pandemic.

Around 60 percent of the districts’ peer institutions are ahead, including many in Texas and Florida. Seven percent are on par with Clark County, and another one-third are behind in the pace of reopening, he said.

Districts that have reopened have found masking and social distancing key in keeping transmission rates down. The growing availability of vaccines for adult staff adds another layer of safety that districts who opened their doors earlier didn’t have, Marianno said.

Taking the leap into reopening is like diving into a cold pool, Marianno said, with a shock and an adjustment period that may lead to the realization that the district was too hesitant to reopen.

‘We should have done it sooner’

“Assuming that our reopening follows what other districts have seen, that following strict protocols can lead to safe reopening, I think we’ll look at this and think we should have done it sooner,” Marianno said.

Why reopen now rather than six months ago, or six months down the line? There has been a tidal wave of school districts around the country announcing their reopening plan in recent weeks, Marianno said, driven in part by a desire to reopen schools before the one-year anniversary of when they were closed. Other factors include the falling rates of COVID-19 transmission and a more favorable stance on reopening from elected and public health officials.

Marianno said this spring’s federally mandated standardized testing also is a factor in reopening, but not the only one, given the public pressure to understand the full impact of the pandemic on education.

“There’s fraught debate about that,” Marianno said. “One of the first touch points our students will have with their schools is a high-stakes test.”

Looking ahead, if the district continues to offer distance learning as an option alongside in-person instruction — as Superintendent Jesus Jara has said the district will do — Marianno said the district must look to best practices by already virtual schools.

“A rapid movement to distance learning taught us that a rapid movement to distance learning is not the way to do it,” he said.

Another major question for the district will be how it communicates with families who are reluctant to send their children back to school.

He noted that already vulnerable communities has been disproportionately impacted by the virus, leading to hesitation about returning among students who may be most in need of in-person support. If those groups aren’t reached, learning gaps could continue to widen, he said.

“That apprehension to return to school shouldn’t be surprising,” he said. “Are we reaching out to those families and saying, ‘We want you back in the classroom and here’s how we’re going to keep you safe?’”

As the reopening conversation shifts to the next school year, families have said at School Board meetings that they need to know now whether the district will offer full-time in-person instruction or not.

Jara said in an interview he expects that determination to come sometime in the spring but that his hope is that the district will be able to offer some level of in-person instruction to all grades.

“Whether it’s in hybrid or five days a week next August, that’s my goal,” he said.

He said the district has also begun conversations with its bargaining units about an extended school year or summer remediation options to address the learning losses over the last year.

Impacts may be felt for decades

Even so, the academic impacts of the pandemic might be felt as far as a decade down the line, said Kenneth Retzl, director of education policy for the nonprofit, nonpartisan Guinn Center for Public Policy Priorities.

As students begin to return to schools, Retzl said, it will be interesting to see who chooses to come back from private schools, how students receiving special education services have fared and how the district addresses students now in danger of dropping out.

“Obviously we can’t change what happened in the past, but understanding how this pandemic affected students and how do we get back on track is important,” he said.

The next question is whether the district has the resources to support and remediate students as they return, Retzl said.

While the district is due at least $300 million more in federal emergency aid, its budget presentations have framed possible state-level cuts as an ongoing uncertainty. Statewide cuts to education after the recession of 2008 are still being cited as hamstringing the district’s efforts to make improvements such as class-size reductions.

In general, Retzl predicts that students will thrive being back in school but pointed out that some thrived under the distance learning model and others would thrive no matter what format their classes took.

A distance learning option works best when parents are engaged, he added. If it continues to be an option at the district, he said he hopes to see families come into it with eyes wide open about the work required to be successful.

“CCSD has had to be innovative, and teachers have had to be innovative, and I hope that innovative streak continues at the district,” Retzl said.

At Dearing Elementary, distance learning required a nimble response to the needs of the student population, which includes a significant number of English learners and students from low-income families.

In addition to dropping off computers, internet hot spots and chargers to students, staff have also responded to individual needs, Assistant Principal Gilliam said. The school’s student success coordinator, for example, visits weekly with a family that recently lost a primary caregiver, in order to help with distance learning questions and allow the grandfather to run errands.

Hybrid learning requires its own solutions

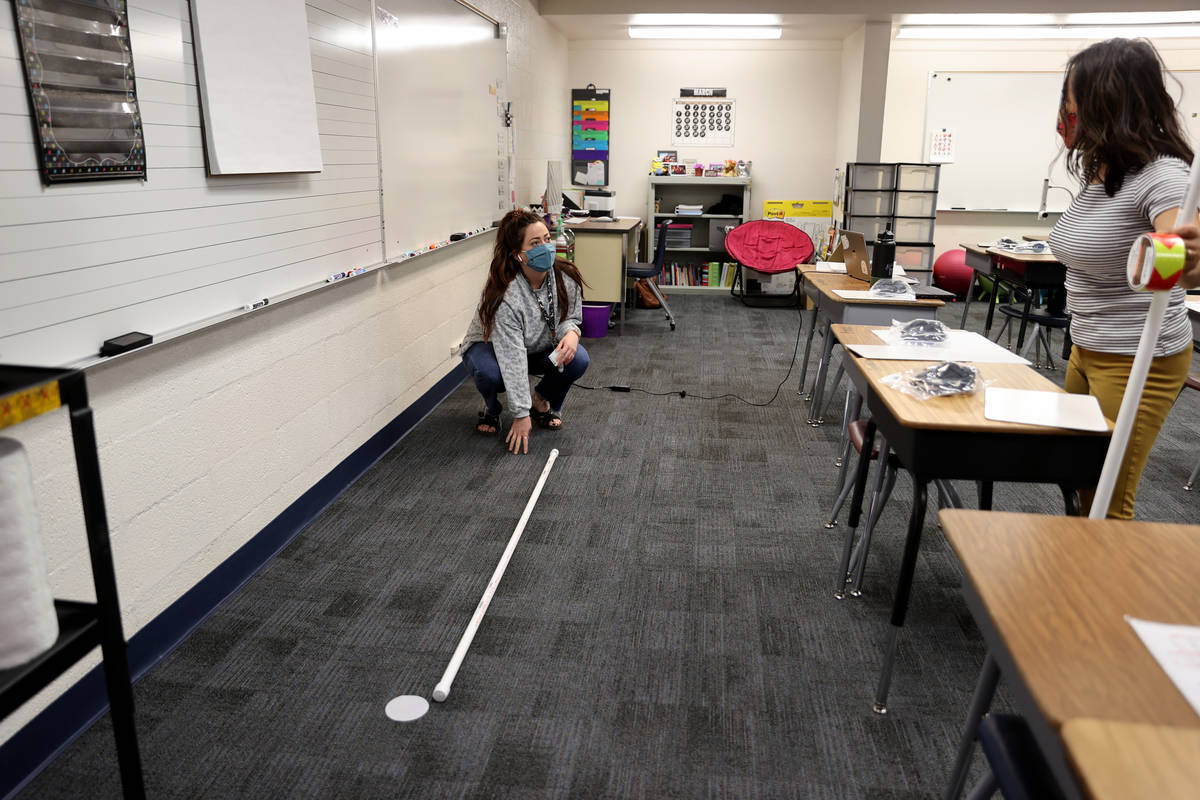

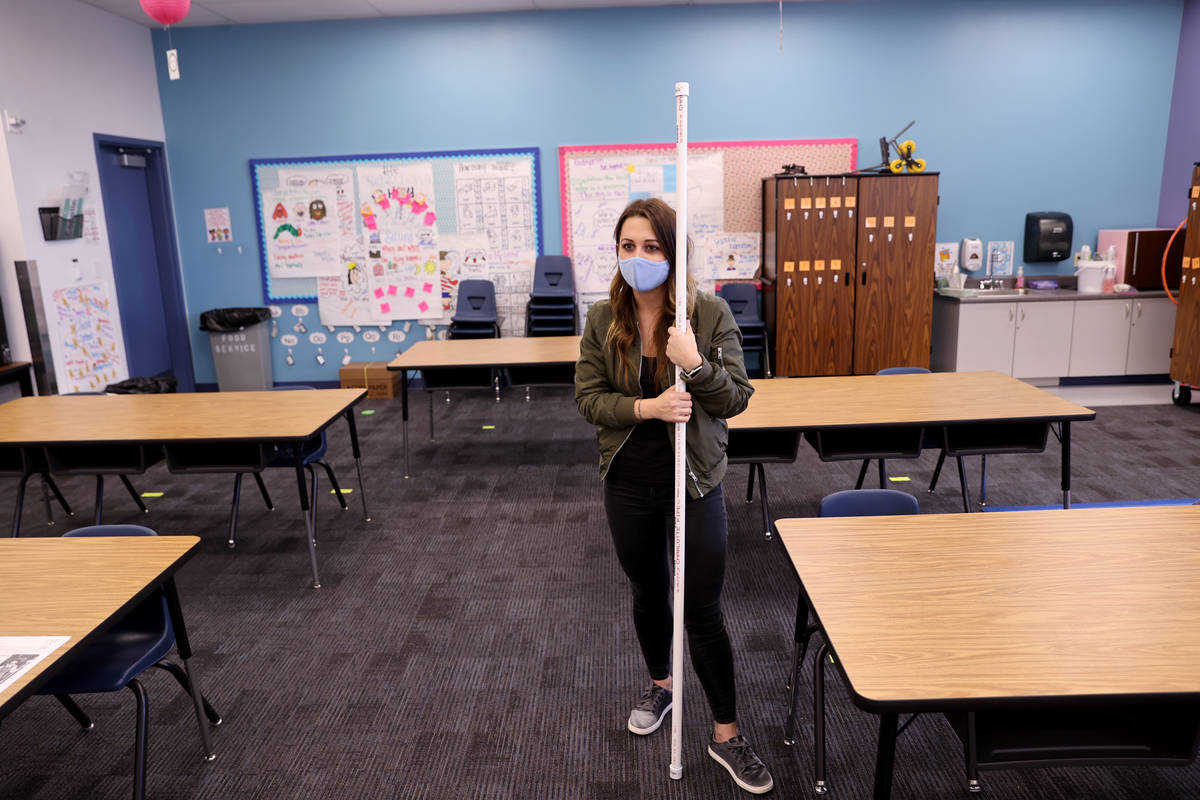

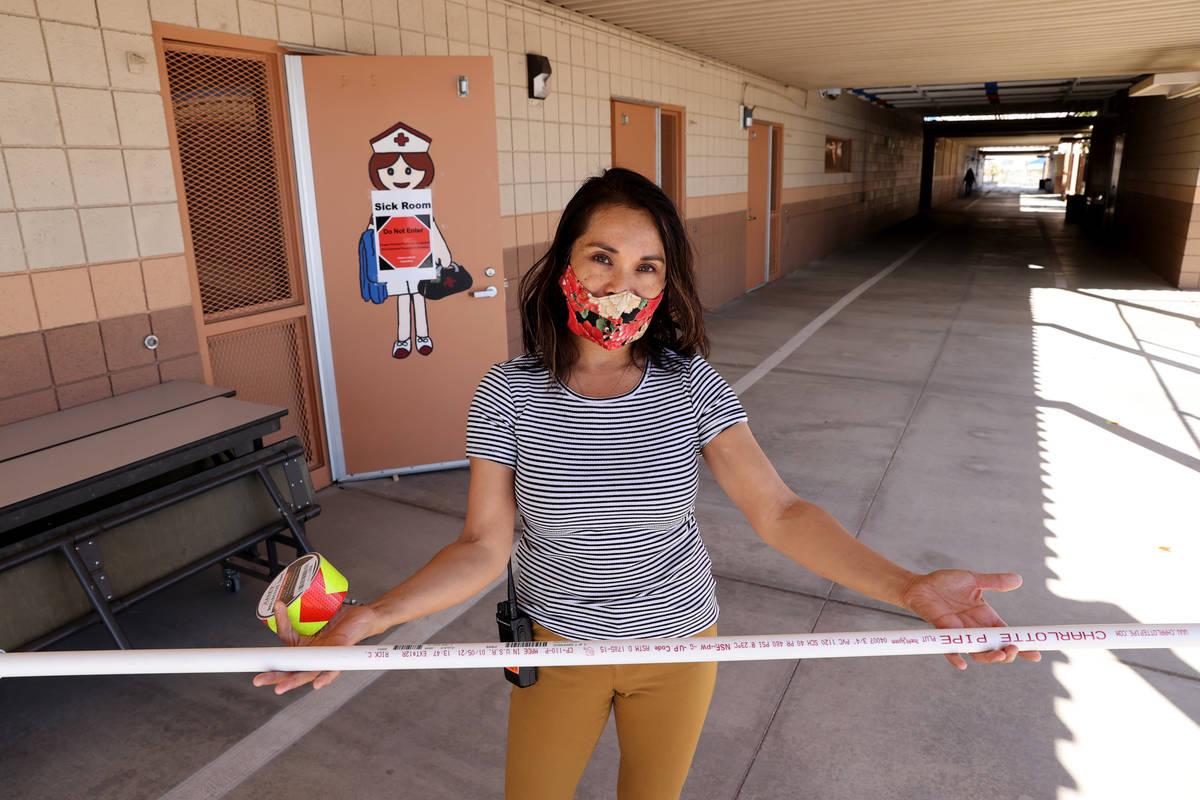

In the final push to reopen the school, staff moved furniture to get classrooms ready and rolled out cafeteria tables so students could eat outside, Gilliam said. The school gave each teacher a 6-foot PVC pipe to offer a visual cue for social distancing. And dismissal will be done in a precise choreography, at staggered times and different gates.

While each change has been tough, second grade teacher Lisa Mullinix noted the adaptability of her students, who have engaged in virtual lessons and even kept the gardening club going during distance learning.

“It’s all about attitude,” Mullinix said. “When I feel sorry for myself, I realize, ‘Oh my goodness. What would this be like if I was little and I couldn’t read and could barely press down down on a key?’ Then I think, ‘Get over yourself, Mullinix. We can do this.’”

Contact Aleksandra Appleton at 702-383-0218 or aappleton @reviewjournal.com. Follow @aleksappleton on Twitter.

RELATED

Youngest CCSD students face big transition to classroom instruction