Here’s what parents need to know about CCSD sickrooms

With full-time in-person instruction resuming for elementary school students in the Clark County School District on Tuesday, a phone call from the school could take on new meaning in the era of COVID-19.

One reason for such a call would be to inform parents that their child has been sent to the school’s sickroom to await pickup after exhibiting symptoms of the disease caused by the coronavirus or being exposed to an infected person.

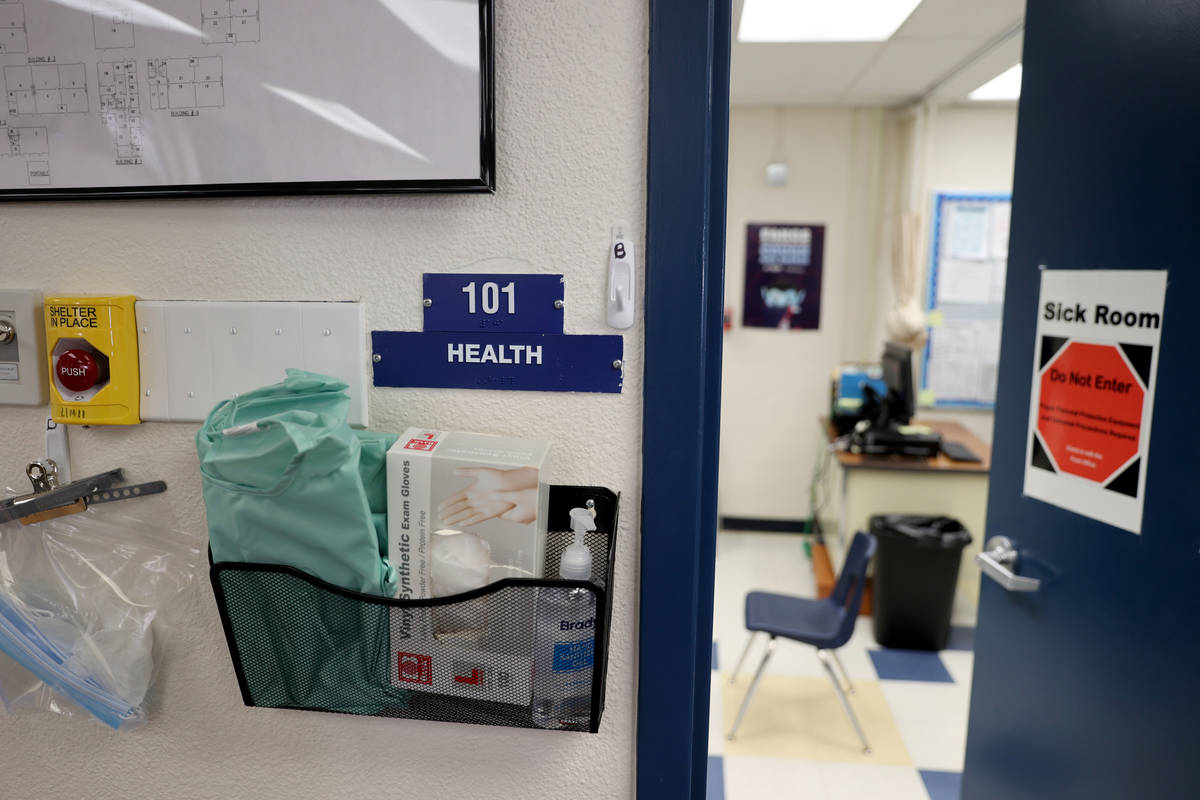

The sickrooms, or isolation rooms, are a key part of the district’s reopening plan and have been equipped with their own supplies and special air ionization systems in an effort to prevent COVID-19 from spreading through a school and infecting other students and employees.

But what happens if a parent or guardian can’t be reached or is unable to pick up the child?

The district told the Review-Journal that schools will follow standard procedures, beginning with making “every effort” to contact a parent or guardian, including possibly sending an attendance officer to the student’s home. The school would also call the student’s emergency contacts.

If a child displayed serious symptoms of an illness — COVID-19 or otherwise — and a parent or other contact could not be reached, a staffer would call 911 for emergency medical services, according to a school district representative.

Emergency services also could potentially be called upon if no one comes to collect a student by the end of the school day, though the district representative said he wasn’t aware of any instances where that has happened.

Transportation question

Older students who drive themselves to and from school may be released on their own at the discretion of the school site, depending on the student’s symptoms. A student with a high fever that could impair their driving, for example, may need to wait for a ride.

The district did not directly respond initially when asked if children would ever be transported home by buses or school district staff if a pickup could not be arranged.

“If staff are unable to contact a parent, existing procedures are followed which include staff following up with emergency contacts or a staff member potentially visiting the home as necessary,” the district said in a statement. A CCSD representative clarified that the purpose of a home visit would be to locate a parent or guardian to come pick up the child.

One district staffer, who asked to remain anonymous citing fear of retribution, told the Review-Journal that he had already been asked to visit students’ homes to alert parents of the need to pick up their children and fears being asked to transport sick students home in the future. The employee noted that there would be no way to enforce 6 feet of social distancing in a car.

The district says it can safely keep sick students in the isolation rooms until someone is reached. Though the rooms have different dimensions, each must be set up to maintain 6 feet of distance between students.

“We will keep the students isolated and safe until someone can come pick them up,” Melinda Malone, the district’s chief communications officer, said at a March 19 news conference.

The district has offered bonus payments to certain employees — including $10,000 for school nurses and $3,000 for first-aid safety assistants — as incentive for working in the campus isolation rooms. Those employees have also been fitted with additional personal protective equipment, such as N95 respirators.

Other groups that worked directly with the public during school building closures — including food service employees, Wi-Fi bus drivers and attendance officers — are to receive a $750 bonus.

COVID at the district

The district reported 150 COVID-19 cases among staff and students in March — a tiny fraction of the 95,889 students and tens of thousands of staffers currently working on or passing through campuses as the district enters its second month of in-person instruction this school year. The dashboard is updated when the district learns of the cases from the Southern Nevada Health District, which can cause lags in reporting.

The dashboard doesn’t differentiate between cases among students and staff still at home and those who have returned to campus.

It showed 85 cases for last month up to March 25 among all elementary school students and staff, some of whom returned to campuses on March 1 for hybrid learning.

Middle and high schools, meanwhile, welcomed some students back March 22 for the first time. For the week of March 22-25, the dashboard showed that middle schools reported fewer than 10 cases among students and staff, indicating that the exact number is greater than zero but withheld for privacy purposes until it reaches at least 10.

For high schools, the dashboard showed 12 cases among students and staff from March 22-25.

The dashboard reports 871 cases for this year and 2,512 since tracking began March 16, 2020.

The Review-Journal has requested more information about which schools have had students quarantine because of on-campus exposures in March. The request has been delayed to April 14.

Contact Aleksandra Appleton at 702-383-0218 or aappleton@reviewjournal.com. Follow @aleksappleton on Twitter.