‘He did terrible, bad things,’ brother says after notorious inmate’s death

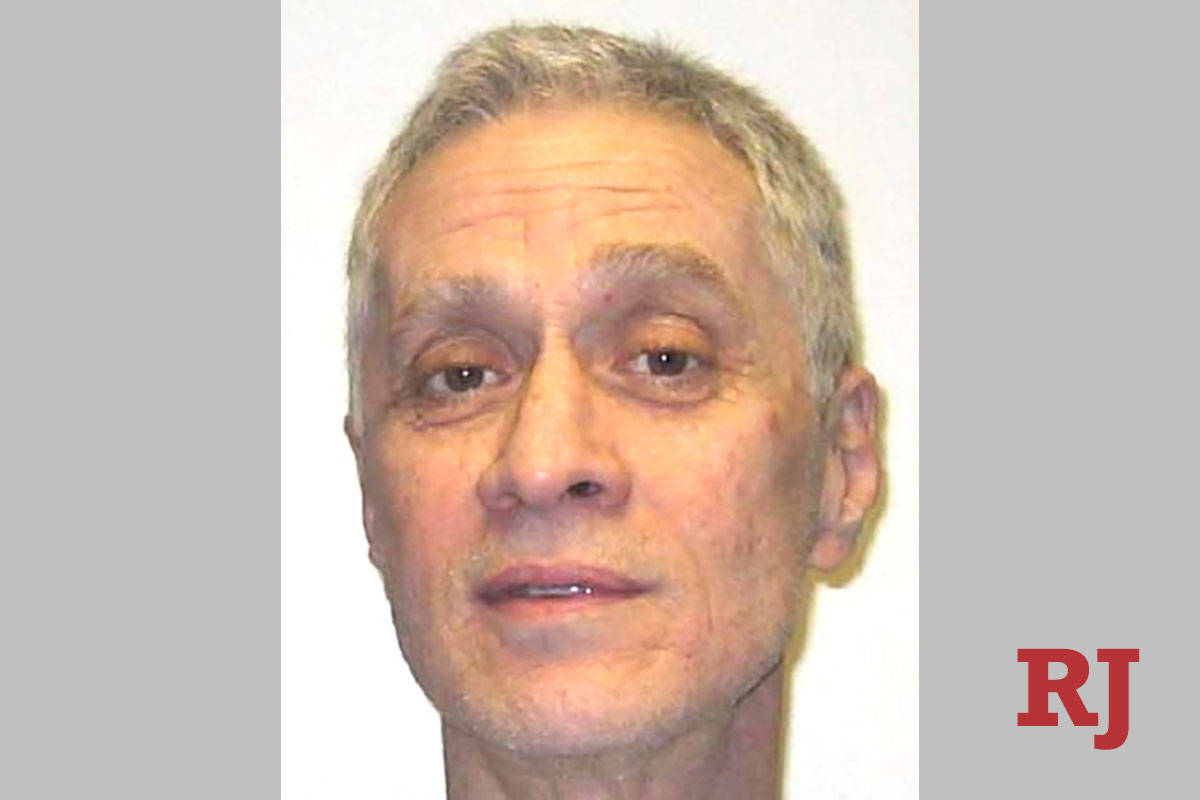

Death row inmate Patrick McKenna, a killer and rapist who spent nearly his entire adult life in prison and was awaiting capital punishment longer than almost anyone else in Nevada, has died at age 74.

He was pronounced dead April 19 at Spring Valley Hospital after a surgery and a series of heart attacks, according to prison officials and his brother.

“He’s probably the most infamous killer on Nevada’s death row,” Clark County District Attorney Steve Wolfson said. “And in my opinion, he didn’t get what he deserved.”

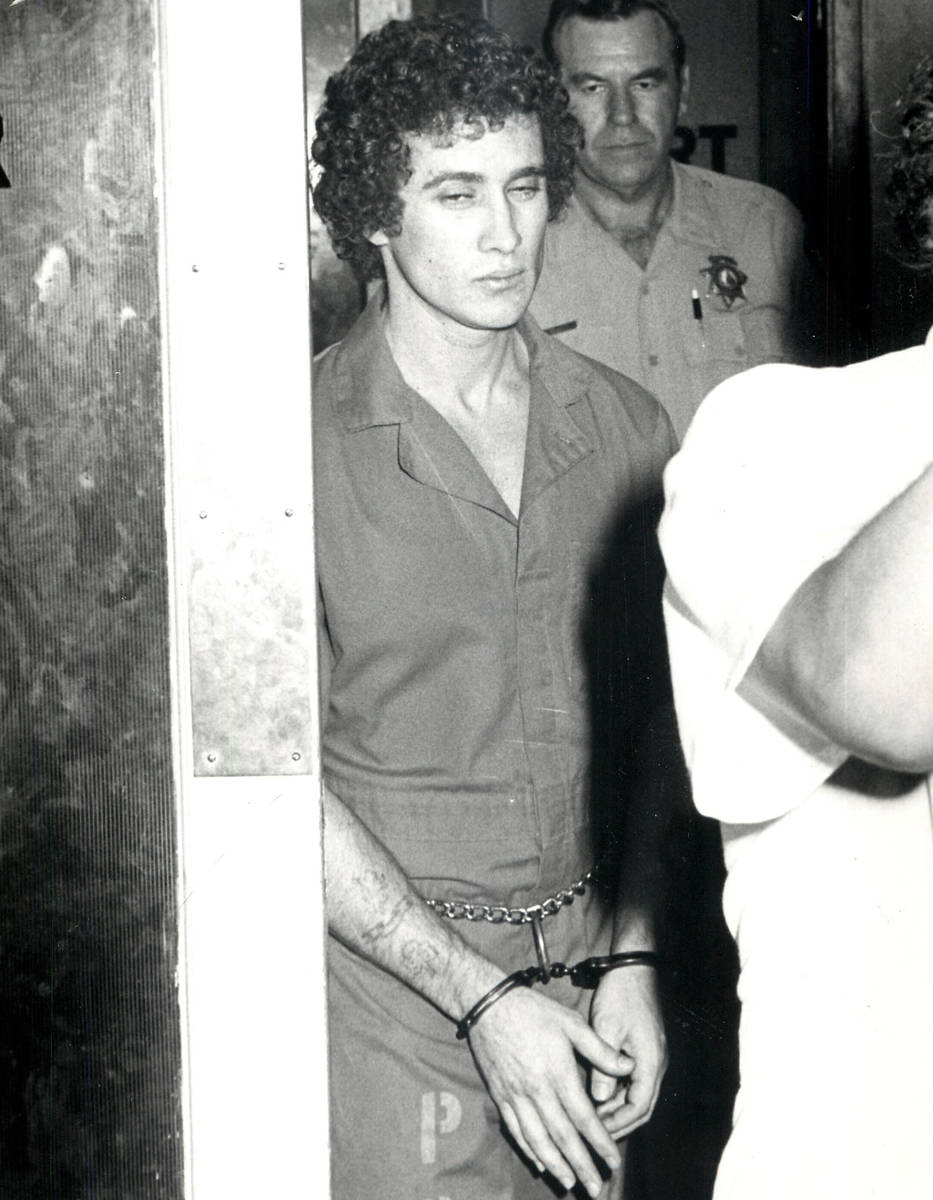

McKenna, long considered Nevada’s most dangerous prisoner, was sentenced to death in 1980 for first-degree murder, kidnapping, sexual assault and robbery with a deadly weapon.

He strangled his cellmate, 20-year-old Jack Nobles, at the Clark County jail in 1979 and had been convicted of beatings, rapes and a stabbing. He continued to commit crimes behind bars.

McKenna’s initial murder conviction in Nobles’ slaying had been reversed twice and his penalty reversed three times. After each reversal, however, a new panel of jurors found him guilty and agreed that he should be executed.

‘A complete change’

He was not afraid of death, those who knew him said, but he did not want the state to kill him.

“I will kill myself before I permit them to do that to me,” he said during a 1989 interview. “I won’t give them that ritual trip. To me, that would be the final indignity.”

His brother Ken McKenna, a lawyer who since has retired, represented his older sibling after the first reversal in the early 1980s.

The younger McKenna said Wednesday that his brother was barely a teenager when truancy officers persuaded their mother to send him to the Spring Mountain Youth Camp on Mount Charleston. She had hoped to steer him from bad influences, but he encountered authority figures who were “vicious and vindictive and basically sociopaths who beat and tortured the kids,” Ken McKenna claimed, calling the experience a turning point for his brother.

“It was a complete change in his personality,” he said. “When he came back from Spring Mountain, he wasn’t there anymore. Pat didn’t exist in that body anymore. He was cold. He was evasive. He committed all those crimes. Nobody’s trying to whitewash that. He did terrible, bad things. But the reality is it would have never happened.”

Patrick McKenna was born in August 1946 in Leadville, Colorado, and moved to Nevada as a child. By age 14, he was sentenced to time in the state’s juvenile facility for stabbing a man.

In 1964, he was ordered to serve 20 years in prison for raping and beating a woman near Sunrise Mountain. A year later, prison officials said they discovered that the bars of his cell had been cut. He escaped prison in 1966 by hiding in a garbage can, and again in 1967 after a guard was taken hostage.

In 1973, McKenna jammed an 11-inch homemade knife into the gut of a correctional officer. Despite that attack, he was paroled in 1976.

He was free for weeks in the late 1970s, living with his brother, and landed a job at Harveys Lake Tahoe casino as a change boy, before being fired after a background check turned up his criminal past, Ken McKenna said.

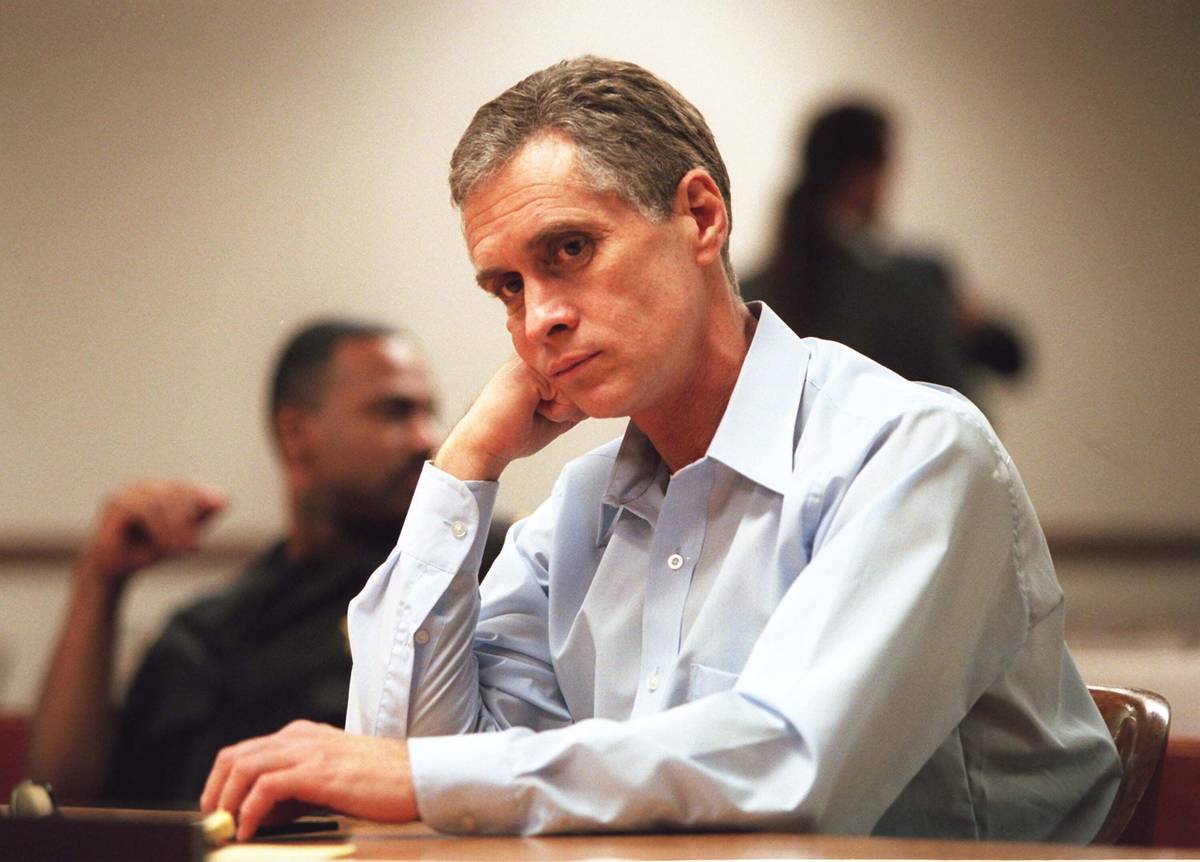

Retired Nevada Supreme Court Justice Michael Cherry, a former public defender, represented Patrick McKenna on the rape charges and during his first trial for the Nobles killing. Cherry had asked the jury to spare his life, but he said Wednesday that his client stopped him from presenting mitigating evidence that could have saved him from the death penalty.

“I tried my best for him,” Cherry said. “I knew his background was partially responsible.”

Post-conviction crimes

Patrick McKenna killed Nobles shortly after a jury convicted him of raping two women in 1978 at a Paradise Road motel.

Prosecutors at the time said that the strangulation occurred after Nobles refused to engage in a sex act. But the two also may have had an argument over a chess match, according to news reports at the time.

Patrick McKenna and two other inmates took over the Las Vegas city jail annex for 44 hours in August 1979. The standoff ended after his accomplices died from gunshot wounds. Patrick McKenna was tried and acquitted of murder in the standoff, but he received a 92-year prison sentence for an escape attempt.

In 1981, he and another inmate acquired a pistol and took several hostages for two hours at the Nevada State Prison in Carson City.

Authorities have said Patrick McKenna also masterminded a death row escape plan that was foiled in 1991 at the Ely State Prison.

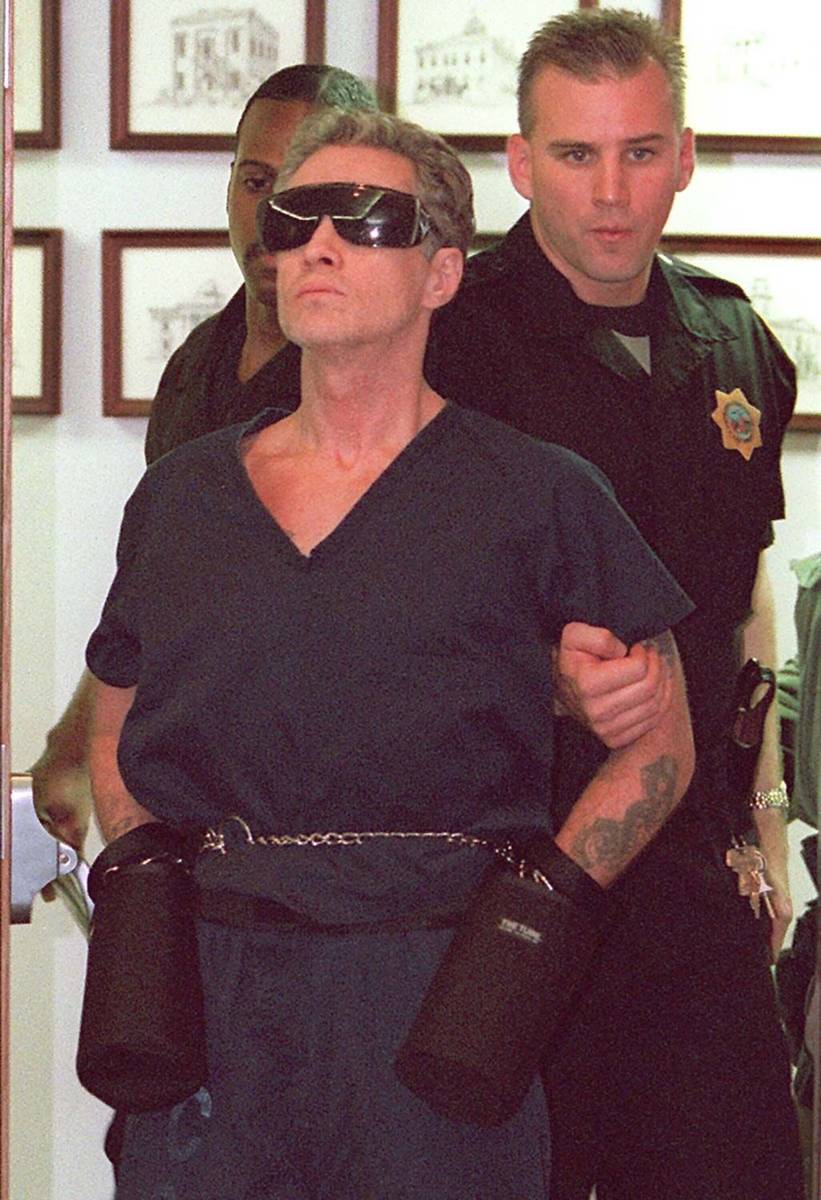

Former prosecutor Douglas Herndon, now a Nevada Supreme Court justice, persuaded jurors to sentence Patrick McKenna to death in 1996, the third time a panel had done so.

In an interview Wednesday, Herndon remembered the level of added security at the courthouse, where authorities were concerned about an escape attempt. A special hole was cut into a wall of the courthouse to allow for easier access from the jail, he said.

“It was like this indoctrination of the history of crime in Nevada,” Herndon said, referring to the “breadth” of Patrick McKenna’s crimes.

Death revives debate

His death came after the Nevada Assembly approved a bill to abolish capital punishment. The legislation still must be passed by the Senate.

Only Edward Thomas Wilson, convicted in the 1979 killing of undercover Reno police officer James D. Hoff, for whom a memorial to fallen officers is named, has served on death row in Nevada for longer than Patrick McKenna.

“If you want a primary example of how broken the death penalty in Nevada is, look at Patrick McKenna,” said Scott Coffee, who sits on the Nevada Coalition Against the Death Penalty. “He was sentenced to death in multiple occasions on the same case, and ends up dying of natural causes after 40 years.”

Coffee said Patrick McKenna “is a guy who, to some extent, thumbed his nose at the system the whole way through, and there was nothing they could do about it.”

Veteran criminal defense attorney Tom Pitaro said capital punishment in Nevada “has no real effect or practical meaning.”

“It’s not that he beat the death penalty,” Pitaro said. “It’s that the death penalty was not functional.”

Wolfson said Patrick McKenna’s case pointed to problems in the appellate system, rather than with the penalty.

“He’s the poster child for an example of how the system is flawed and needs to be fixed,” Wolfson said. “It’s the fact that even after two or three juries imposed death, he still got to be alive for 40 years.”

Ken McKenna last spoke to his brother a few weeks before his death. The elder McKenna had been sent to High Desert State Prison to undergo surgery in Las Vegas to remove a cancerous tumor on his liver, according to his brother. He survived the surgery but later suffered a series of heart attacks and died.

This week, the younger McKenna, 67, reflected on his own life, which he now spends on a sailboat on the East Coast, as he thought about his four other brothers, particularly the convicted killer. Authorities had once suggested that Ken McKenna also attend Spring Mountain Youth Camp, but his mother refused after his older brother became a criminal.

“It wasn’t his nature that created the Pat McKenna that spent all that time in prison,” Ken McKenna said. “It was the nurture part of his life. You can’t come down on nature, ’cause the rest of us are fine.”

Contact David Ferrara at dferrara@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-1039. Follow @randompoker on Twitter.