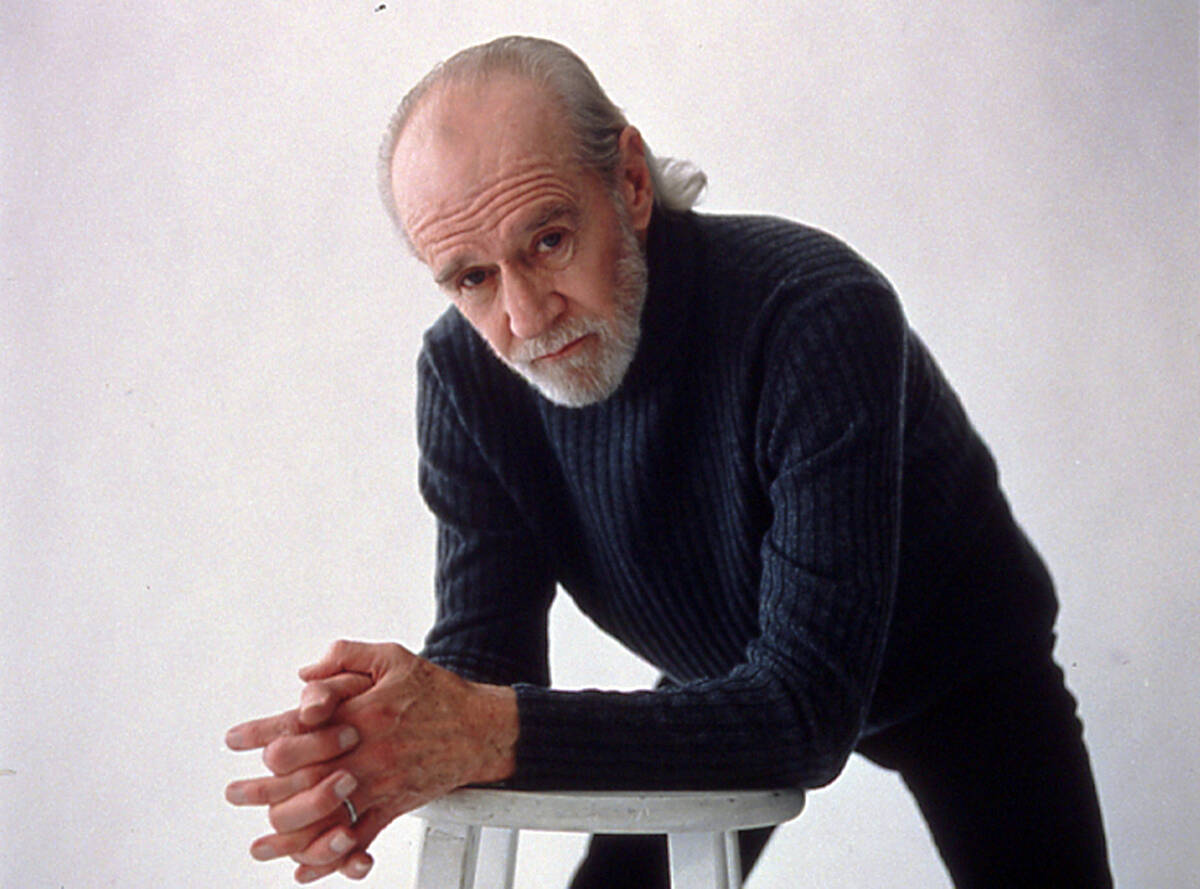

Dennis Blair opens up — again — for George Carlin

Veteran comedian Dennis Blair opened for George Carlin for the final 18 years of his career. That stretch included Carlin’s final show at The Orleans Showroom on June 15, 2008, just a week before his death of heart failure at age 71.

The two shared car rides and backstage hangs and generated a working friendship and mutual respect.

Naturally, Blair was interviewed for Judd Apatow’s highly anticipated documentary, “George Carlin’s American Dream,” which premiered on HBO this past weekend.

But he’s nowhere to be found despite being interviewed for an hour and a half.

That is, unless you notice the photo of the Bally’s marquee, circa the 1990s, with Blair’s name in lights under Carlin’s.

Such famous comic performers as Chris Rock, Jerry Seinfeld and Stephen Colbert made the cut. Blair’s short explanation for being omitted: “Show business. They went with more famous names.”

But Blair — a busy stand-up and singer-songwriter, and a Vegas resident for nearly a decade — had a lot to say this week about his time with Carlin.

Johnny Kats: Tell me about Carlin’s last performance at The Orleans. What do you recall from his last performance?

Dennis Blair: Well, more than that last night was the two years preceding that night. One of the great things about George was we just had great times backstage. He would leave me notes that I can’t even repeat. We had a Jerry Lewis fetish there for a while. We’d go, “Floyden!” — which isn’t even a word — in Jerry’s voice. He’d leave me Jerry Lewis stuff, Jerry’s photo with a voice bubble over it shouting, “Floyden!” He was a lot of fun on the road, until two years before he died.

What happened then?

All of a sudden, things changed. He started getting kind of grouchy, kind of snapping at people, and everyone is going, “What is this all about?” He would close his dressing room door, when he used to keep it open so you could just go in and B.S. with him. He was not smiling, and he just kind of slowed down. Then we found out he had been fighting an addiction to Vicodin, and he was having real physical problems.

Did you know what condition he was in when you worked together?

The last show, oddly enough, at The Orleans, I guess he was getting some sort of treatment where he was seeming to be better, was feeling better. And my wife, Peggy, actually went up to him and said, “George, you look good.” He said, “Thanks!” and a week later he had died. But that last week at The Orleans, he was OK. He didn’t have all the energy he used to have, but he was OK.

He played Las Vegas quite a bit when you were with him, also at Bally’s, the Stardust, the Hollywood Theater at the MGM Grand. I had heard about a lot of walkouts during his shows, especially at the MGM Grand. What happened there?

Oh, yeah, you go to Vegas and you don’t necessarily go to see George Carlin. You have like 8 million shows, and if you can’t get into a “Ka,” you might say, “Let’s try this show. Maybe he’ll be funny.” He would be doing his usual stuff, and people would walk out, which was a problem. But he didn’t change a word. He didn’t fashion his show any differently … But it was a lot better at The Orleans, off the Strip, because you had to go find him there and they were more his fans.

You were an established comic by the time he brought you on. How did you become his opening act?

It was 1988, I had this really good agent at the time who would call me up and go, “You want to open for the Four Tops? You want to go on the road with Laura Branigan or the Miami Sound Machine?” And I would say yes 99 percent of the time. He called one day and said, “You want to open up for George Carlin for three months?” I said, “Let me think about it — yes!”

You had worked with Joan Rivers and Rodney Dangerfield, too. That must have had something to do with you joining Carlin on tour, right?

Maybe. I never found out the reason. (Laughs.) I’m not the guy who questions why it happened. But we got along immediately. I clicked with his audiences. After three months, he said, “Do you want to stay?” and I said, “I have no other plans.”

How was he to work with compared to the other stars you toured with?

Rodney I was with for 3½ years, and he demanded almost all of my time. We wrote together a lot, we did the movie “Easy Money” together, we’d hang out at his house, we’d hang out. He just wanted company. Joan Rivers was like a den mother. I’d get a call at 10 o’clock in the morning. She’s telling me we’re going on the Caesars yacht on Lake Tahoe. “I’d say, ‘We?’ Who are we?’ And she’d say, “You, me, Garry Shandling, and my manager.” George and I had great times in the rental car on our way to the theater, from the hotel. We had a lot of fun backstage, but once we went back to the hotel, we wouldn’t see each other.

Got a road story to share?

He had what was called the “zippo-bango” way of leaving a theater. He didn’t want to hang out and have people come back to the dressing room. So five minutes before the end of the set, he’d have me pull up the rental car and he’d get in the back and I’d take off. We’d be on our way to the nearest 7-Eleven for snacks just after the show ended.

You’ve said one of the stories you told for the documentary was about his final night at the Copacabana in New York, I think in 1969. Carlin had told you about that night because it came after he changed his stage persona.

He grew his hair and beard, and the Copacabana was a very straight-laced place. He was having a horrible time, with that crowd. Near the end of his last performance, he just crawled under the piano with the mic and kept saying, “Fire me. Please fire me.” The spotlight followed him down and turned into a pin light until going dark. It was very dramatic. He said he knew he didn’t belong there. Then he went on the college circuit and became the new George.

He was the first host ever on “Saturday Night Live.” What was your conversation with him about that momentous occasion?

One day I just brought it up, and he said, “I don’t remember it.” (Laughs.) He said, “Anybody who’s taken copious amounts of cocaine knows, if you looked into my eyes, you’d realize I was higher than the Empire State Building.” So, apparently, he had no memory of his first hosting, and only hosting, job on “SNL.”

Have you seen the documentary?

No.

Do you have plans to see it?

Maybe, when I get over my hurt feelings.

Is it painful, not being part of it?

It isn’t as if I didn’t see it coming. Ten percent of me thought, you know, I won’t be surprised if I don’t make the final cut. They sent me an email saying I’d be surprised if I’m not in it. They said they wanted to concentrate on George’s work ethic and his material. They also said I’d be surprised at how many famous people they had to cut.

A lot of big names did speak to his career, his influence.

I know, and some of the people I’ve heard are on it were people that George didn’t particularly care for. But I’m not going to name any names.

His material is still being shared on social media, his comments about climate change and public policy are still relevant today. He’s being celebrated as much now as ever. Does he deserve all the accolades, and what is his place among the all-time greats?

He absolutely deserves the accolades. I’d say he’s in the top five, if not the top three. You have the classic list of George, Richard Pryor and Lenny Bruce. My own list would probably have Bill Burr and Brian Regan, guys who just consistently make me laugh. But even some of the physical stuff George did, a bit about people with the roving eye, who look at you and also look over to the right. Even after seeing his act so many times, I would go out specifically to see some of his stuff, like, “Oh, he’s doing this bit. I’m gonna go out and watch it again.”

John Katsilometes’ column runs daily in the A section. His “PodKats!” podcast can be found at reviewjournal.com/podcasts. Contact him at jkatsilometes@reviewjournal.com. Follow @johnnykats on Twitter, @JohnnyKats1 on Instagram.