‘Highly problematic’: Metro officers’ use of app thwarts transparency, critics say

Transparency advocates are raising concerns after court records showed that a Metropolitan Police Department sergeant accused of illegally detaining people on the Las Vegas Strip used an app called Signal, known for its end-to-end encryption and disappearing messages, to communicate with his squad while out on the job.

“The way that we communicate, we use an app called Signal,” said Justin Candolesas, a Metro officer who was part of Sgt. Kevin Menon’s squad, testifying in front of a grand jury that later indicted the sergeant.

Menon is facing charges that include oppression under the color of office, battery and, in a separate case, possession of visual pornography of a person under 16.

Some experts say that the use of the app by Metro officers thwarts transparency and raises concerns about whether the department is in compliance with Nevada’s public records law, which states that communications between officers while on duty are considered a public record.

The problem is that Signal allows for messages to be automatically deleted after a specific time frame, experts said.

This means that if a person or news organization submitted a public records request pertaining to an incident in which officers had been using Signal to communicate, records of those officers’ communications might not exist anymore. Signal’s end-to-end encryption and the fact that it is not a platform that the government has access to also means that even if those records do still exist, they may not be found and turned over in response to a public records request.

Under state law, messages pertaining to work that are sent between officers while on duty are among the records subject to the Public Records Act, according to Las Vegas Review-Journal Chief Legal Officer Ben Lipman and American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada staff attorney Jacob Smith.

Candolesas said officers communicated via Signal “whether it be on our personal phones or work phones,” records show.

When another Metro officer, Stephen Corsaro, was asked by prosecutors whether Signal messages are kept as records, Corsaro responded that the app has an automatic delete function.

“There is no justification for using Signal other than the fact that it is end-to-end encryption and it automatically deletes the messages,” Smith said.

Is the use of Signal by police officers a violation of Nevada’s open records law?

Metro said in an email Wednesday that per Nevada law, mobile applications that use end-to-end encryption or “any other means with the intent to avoid the creation, retention or lawful discovery of records or data relating to the communications of peace officers” are prohibited.

The department did not specifically respond to emailed questions about whether any other officers use Signal, or whether officers have their settings set to automatically delete messages.

Smith said the statute is a “clear prohibition on using software apps exactly like Signal,” and that Menon and his squad’s use of the app in the course of their official duties is “highly problematic.”

“Those records should be able to be tracked,” Smith said.

While the use of Signal itself may not be in direct violation of the Nevada Public Records Act, its use indicates that there are likely violations of the act happening, he said.

Beyond the potential destruction of public records, David Loy, legal director for the First Amendment Coalition, said using apps like Signal also can create problems for the production of public records.

“Whenever public officials or employees are using personal platforms, like their own personal phones or accounts — their own personal Signal accounts — it can potentially frustrate public access to those records,” Loy said.

In some cases, communications made on personal devices or accounts still can constitute public records, Loy explained. In 2018, the state Supreme Court ruled that public employees’ personal devices are open to public inspection and subject to the state’s public records laws.

But there can be “practical problems of access, and we have to depend on the employees to search their own devices,” Loy said.

The fact that the government does not have access to employees’ Signal accounts is more of a problem for public records access than encryption, explained Aaron Mackey, free speech and transparency litigation director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

“The government doesn’t have a copy,” Mackey said. “Or if it does, it’s not able to actually render its readable content, because it’s encrypted.”

Concerns surrounding Metro officers’ use of the app

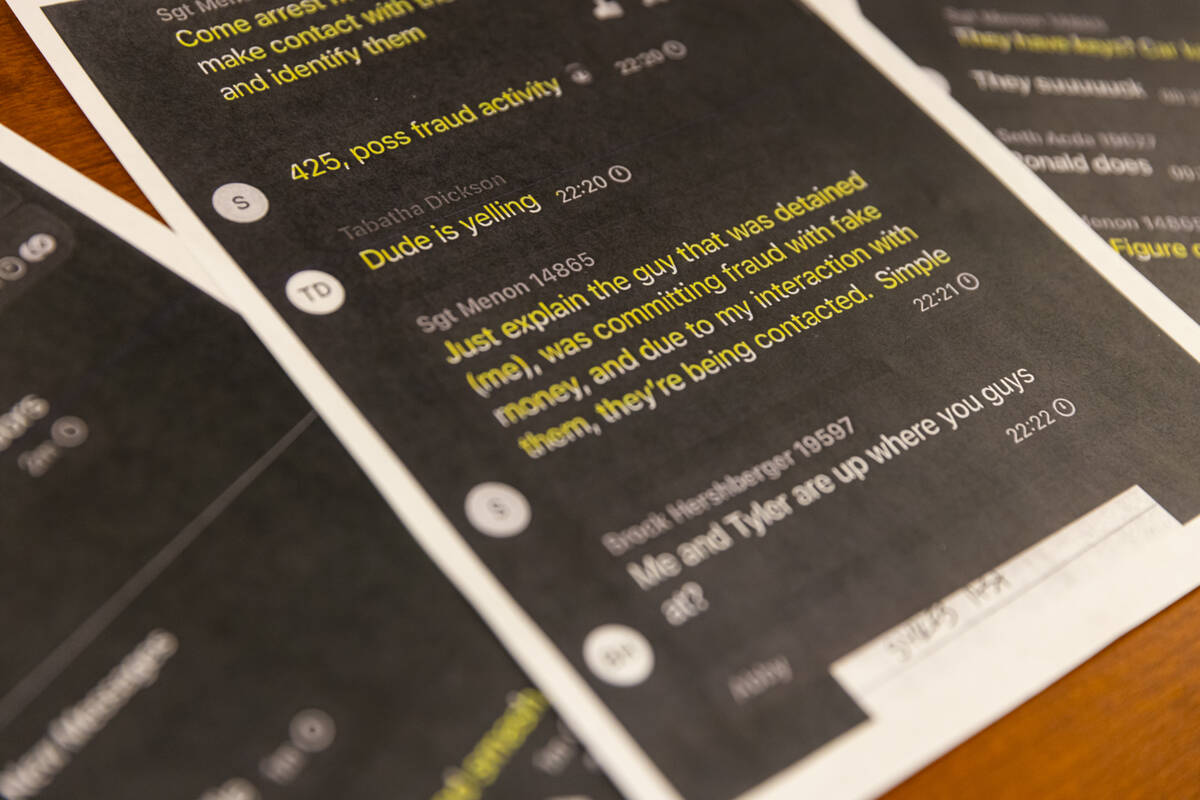

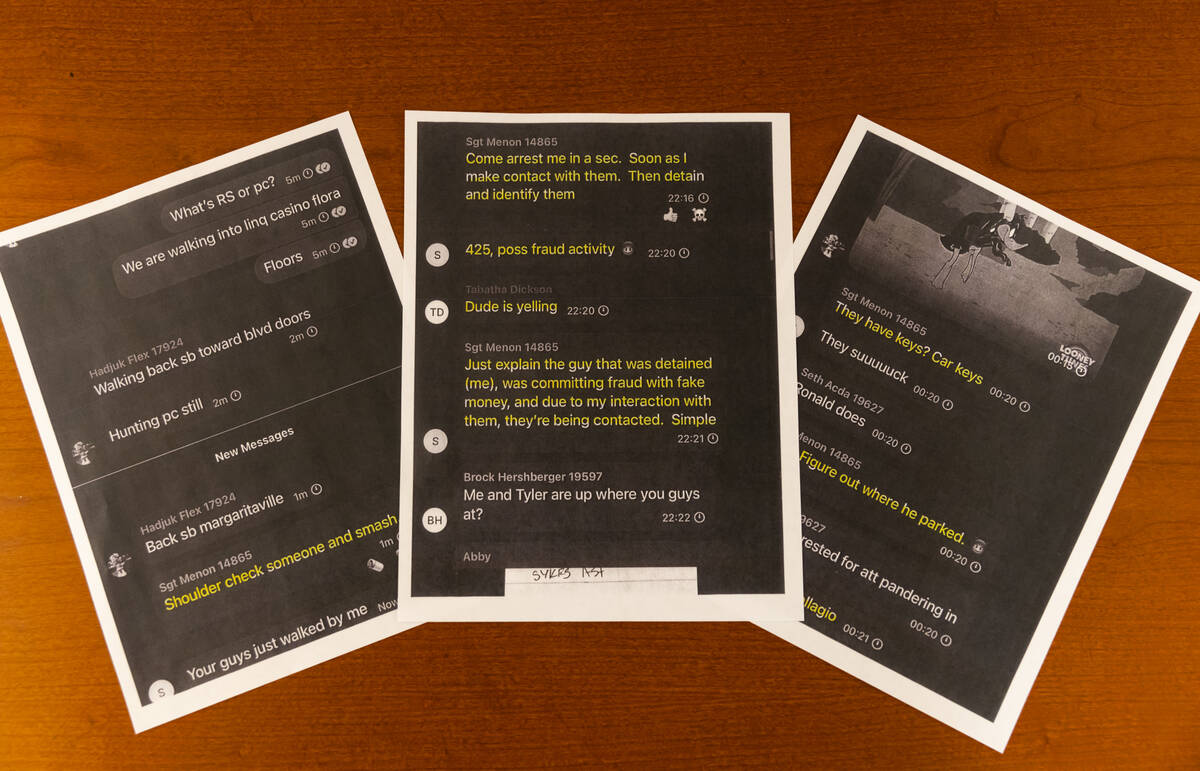

Screenshots of conversations between Menon’s squad on Signal show that officers used the app to communicate important information, such as why someone was being detained.

“That’s how we communicate whether or not like when plainclothes officers have reasonable suspicion or probable cause to stop someone,” Candolesas testified. “That’s when we come in.”

Plainclothes officers are officers dressed as regular people, with nothing identifying them as police, according to Metro. Menon acted as a plainclothes officer on several occasions in which he is accused of unlawfully detaining someone.

According to Metro documents, plainclothes officers are not meant to interact with members of the public when working on a team with uniformed officers in the kind of operations Menon’s squad was conducting on the Strip. Instead, unless in the case of emergency, they are only meant to act as “spotters” and communicate to their colleagues why someone needs to be stopped by a uniformed officer.

Signal, records show, facilitated this crucial communication between plainclothes and uniformed officers.

Police testified that images of the officers’ conversations were screenshots of the chat. But if those messages had been automatically deleted and screenshots hadn’t been taken, those records would have been lost.

The app’s settings do allow a user to turn off disappearing messages. But if public officials use applications that provide them with this option, Mackey said that it’s left to individual officers’ discretion as to whether records are retained.

Loy said the issue is not about the good or bad faith of particular individuals.

“I’m not here to demonize any particular officer,” he said. But, “you can’t have government accountability without governmental transparency.”

“Any system that depends on people not making a mistake is a system doomed to fail,” Loy said. “We should be able to rely on the systems we create to ensure transparency and accountability without having to depend on people not making mistakes.”

The “What Are They Hiding?” column was created to educate Nevadans about transparency laws, inform readers about Review-Journal coverage being stymied by bureaucracies and shame public officials into being open with the hardworking people who pay all of government’s bills. Were you wrongly denied access to public records? Share your story with us at whataretheyhiding@reviewjournal.com.

Contact Estelle Atkinson at eatkinson@reviewjournal.com. Follow @estellelilym on X and @estelleatkinsonreports on Instagram.