Westminster celebrates 50 years of friendship, service

What did they call it … “Bowling for Blessings”?

“From what I know, they carried the organ into the bowling alley every Sunday,” says Kathie Slaughter, a congregant of Westminster Presbyterian Church for 39 of its 50 years, recounting its earliest history.

Half a century back, prayer services were conducted in what is now Arizona Charlie’s but was then the Charleston Heights Bowl, in its banquet room. Sermons competed with the crash of strikes (for those God smiled upon) and 5-10 splits (for those he didn’t). Courteously, the bartender yelled for drinking customers to keep it down.

“They adjourned for lunch afterward and maybe some games of bowling,” Slaughter says. “And some of the bowlers would send their children over. It’s probably one of the more unusual beginnings of a church.”

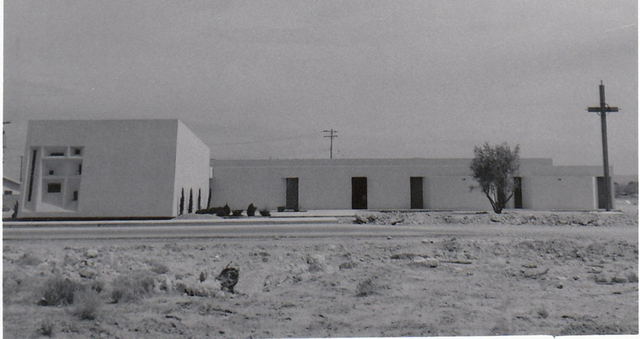

With that untraditional establishment in 1963, and under the supervision of organizing minister Gus Harris, Westminster Presbyterian Church took root. After members drew up an official charter in 1964 — the basis for its 50th anniversary celebration today at the church — it opened as its own home, sans rental shoes and gutter balls, on West Lake Mead Boulevard in late 1965.

“The membership has yo-yo’d over the years — it’s been as much as 200, and down to 25, and now we’re up to over a hundred,” says church member Melva O’Neill. “We’re a small enough church that we share joys and concerns at a worship service. People are free to stand up and say, ‘My cat died and I’m very sad,’ from that to ‘My husband has cancer.’ It’s therapy and family.”

Talk to members and its spiritual leader and you find there’s a handy shorthand for their affection for the Westminster Presbyterian Church that comes down to this: intimate (see above), diverse, friendly, liberal, tolerant, charitable and quirky.

Diverse? Check. “It’s close to the ideal situation when you’re reaching races of all kinds. We have Latinos, we have Asians, we have blacks and we have Caucasians,” says the pastor, the Rev. Adolph Kunen, who points to multiculturalism as one of the reasons he accepted the post in 2010. “It was welcoming and inclusive and willing to see a new day in the life of the church.”

Citing the church as connective tissue between ethnic communities in town, Slaughter adds: “It’s an opportunity to mix with people you might not normally see in your daily life.”

Friendly? Check. “Most churches have a little time (before services) where people greet each other,” Slaughter says. “They greet people and shake hands with people beside them and behind them. In our church they run all over the place and greet everybody. They’re usually not back in their seats by the time the music starts. You can’t stop some people from charging up the aisle to hug.”

Tolerant? Extra check — especially when considering the church’s history. Though Presbyterian churches, by and large, reflect a comparatively liberal attitude, Westminster came of age in a conservative neighborhood of Nevada Test Site workers when the Cold War was at its chilliest. One of them, health physicist and radiation safety specialist Layton O’Neill, sang in the church choir in the 1970s and ’80s. Standing shoulder to shoulder with him was his friend, Pete Ediger, who campaigned to have the site decommissioned.

“They were friends but they had completely different points of view,” says O’Neill about her now bedridden, 86-year-old husband, and Ediger, who has since died. “Peter had been a Mennonite minister, he was all about peace. In church on Sundays, they put their differences aside.” Occasionally, at meetings of the church’s men’s group, each would bring in speakers to advocate on behalf of their own positions.

“They discussed it a few times but they weren’t changing each other’s minds. We felt he had his right to protest. But we saw a lot of Peter at the church.”

Liberal? Definite check. Three of its ministers have been women — one of them divorced. “I grew up Baptist and I had been divorced,” O’Neill says. “Here I found a church that accepted me for who I am.”

Quirky? That’s a check you have to literally take on faith — as in faith healing. “That was on my heart to do, to do justice to the healing ministry of Christ — we take him up on that, we lay hands on the sick and we pray for them. And people have been healed much of the time,” Kunen says.

Forget that evangelical caricature in which a minister, his spittle flying, shouts pleas to God to perform an instant miracle through him, and a blind man suddenly cries, “Hallelujah! I can see!” as a congregation shrieks and faints.

Instead, Kunen says, it is as simple as a conversation.

“Someone can just say, ‘Oh boy, I’ve got this pain in my back,’ and I’ll say, ‘Would you like me to pray for you?’ and we’ll go to a quiet place. Within the course of a week, I’ll pray for about five people. We do it softly and with a gentle manner, not with great flamboyance to make a big show of it, and people respond to that. We do set aside time for healing worship services, but it’s not a big ego thing.”

Charitable? Double-check, especially if you run across Michael Coughlin, a church deacon who joined in 2011. After being an observant Catholic for 45 years, Coughlin says he was driven off by the dogma. Over three months, he attended Westminster on Sundays and was persuaded to make a change.

“I went looking for God, and meeting people there, it was more about the love of Jesus Christ,” says Coughlin, a former Marine who fought in Operation Desert Storm, among other postings. Though he was already affiliated with Westminster, Coughlin was homeless in 2012 and 2013 and, using the church as his base, chose to continue living on the streets to aid others in similar straits.

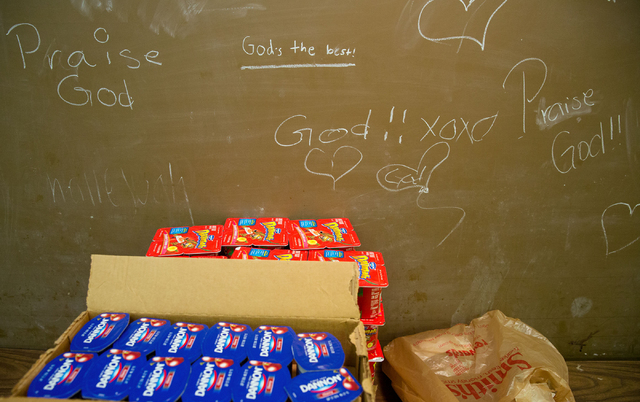

“It was something God asked me to do. I had been very ill, and I got quite the overwhelming feeling of, what have I ever done for anyone other than myself or my own, and I realized — nothing,” Coughlin says. Now living in a trailer and, with church assistance, Coughlin helps homeless people find clothing and food — the latter including the church’s food pantry, associated with Three Square food bank.

Having gained survival smarts as a Marine, Coughlin passes on that knowledge, including bivouacking and camouflaging to help them stay safe, and, pairing with a friend, began a “bicycle ministry” in which they repair old bikes for use by the homeless.

“If there’s a job they want to get to, or Social Services, it’s a horrible thing to have to come up with $5 (for public transportation), so this changes their lives. Suddenly they’re getting places, not stuck in one little neighborhood,” Coughlin says.

“And the church jumped in to help me. The church is the hub of everything I do. It’s a big wheel and I’m just one of the spokes. The times when I think everything is going down the toilet, my friends in the church and my belief in the church make me believe it will all work out.”

Much changes over 50 years. Inside these walls, congregants say, the core principles have not. “There is a passion to reach out to those who are outside the walls of the church,” Kunen says.

“We have people living around us who have needs. We welcome them into our church and they get a sense of what it is to be welcomed into the family of God. Our saying is: ‘a gracious people serving a gracious God.’ ”

GIVE THANKS AND CELEBRATE

Westminster Presbyterian Church , 4601 W. Lake Mead Blvd., will have its 50th anniversary celebration at 5 p.m. Saturday. The celebration will feature dinner (suggested donation $5), a musical program, historical photo slideshow and history of the church (702-648-8437).