Officer who shot, killed Gulf War veteran fired

For the first time in Las Vegas police history, an officer has been fired for an on-duty police shooting.

But it’s unclear if former officer Jesus Arevalo, who shot and killed unarmed Gulf War veteran Stanley Gibson in 2011, is done with the department. He has 30 days to appeal his firing, which was effective Tuesday.

Chris Collins, executive director of the Las Vegas Police Protective Association, the union that represents rank-and-file officers, said he isn’t certain if Arevalo will appeal. If he does, an outside arbitrator will make the final decision about his job.

“Time is beating him up pretty good,” Collins said. “He’s been living this thing for two years now. I don’t know if he’s got any fight left in him.”

Arevalo’s firing came a few weeks after his Sept. 30 hearing before the department’s pre-termination board, which unanimously recommended his dismissal.

The pre-termination board agreed with the department’s Use of Force Review Board, which first recommended Arevalo’s firing in May.

The Use of Force Review Board is a seven-member panel of three officers and four citizens who review police shootings and other serious use of force.

The pre-termination board is a smaller board of three internal officers that review termination proceedings. Clark County Sheriff Doug Gillespie has the final say in any firing, and in Arevalo’s case he agreed with his two review boards.

“Based on Officer Arevalo’s actions during this event it was the decision of the pre-termination board he lacked the ability to make sound decisions in situations routinely faced by police officers,” a Wednesday statement from the department said.

Although Gillespie and his review boards agreed with Arevalo’s firing, there hasn’t always been such harmony.

The Use of Force Review Board recommended officer Jacquar Roston’s firing in April after Roston showed little remorse for shooting Lawrence Gordon in the leg in November. Roston mistook the shine from the label of Gordon’s hat for a gun when Gordon reached under his seat. Gordon was unarmed.

But Roston changed his tune in front of the pre-termination board and admitted his mistakes. That board recommended a 40-hour unpaid suspension, the harshest punishments short of firing at the department. Gillespie agreed.

The fallout from Gillespie’s decision included the abrupt retirement of Assistant Sheriff Ted Moody, who oversaw changes to the Use of Force Review Board and felt the sheriff undermined its integrity.

Six civilian members of the review board also resigned in support of Moody, who later announced his candidacy for sheriff. Gillespie recently said he will not seek a third term.

Gillespie said Wednesday that Arevalo’s case was different from Roston, in part because both review boards agreed.

The pre-termination board comments “pretty much mirrored that of the recommendations made in regards to (Arevalo’s) actions by the Use of Force Review Board,” Gillespie said.

He was able to make a quicker decision on Arevalo compared to Roston because he was so familiar with the details of the Gibson shooting, which was heavily scrutinized, he said.

“I had to prepare on a number of occasions for depositions in the Gibson case,” he said.

Despite the controversy, the Roston and Arevalo shooting reviews were a stark from the department’s past. Before this year, no officer had ever been fired for an on-duty shooting and few were ever disciplined.

But the department adopted new policies in the wake of a U.S. Department of Justice review in the wake of a Review-Journal investigation of police shootings. The Justice Department found the department’s policies were outdated and failed to hold officers accountable.

The Use of Force Board, previously seen as a rubber stamp that justified officers’ actions in all shootings, was overhauled last year.

In a favorable progress report last month, the Justice Department commended the department’s willingness to implement its recommendations and noted the lower number of shootings and the higher instances of discipline when officers failed protocol.

Gibson’s death was one of several high-profile Las Vegas police shootings that sparked the Justice Department’s interest.

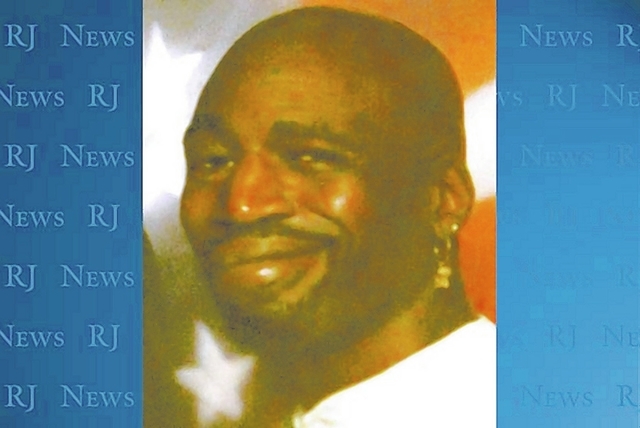

Gibson, 43, was killed Dec. 12, 2011, during a standoff at the Alondra apartments, 2451 N. Rainbow Blvd., near Smoke Ranch Road, which began with a mistaken attempted burglary report.

Gibson’s family said he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder and his mental condition had deteriorated in the weeks before the shooting. Lost, the veteran drove into the apartment complex near his home and was circling the parking lot when officers arrived and boxed his Cadillac between two patrol cars. Gibson refused to get out of the car.

Officers at the scene didn’t know if Gibson had a weapon, and didn’t know he was mentally ill, even though he had two recent contacts with their department. The last encounter was just hours earlier.

Sgt. Michael Hnatuick’s initial plan called for officers to approach the car from the left rear — Gibson’s blind spot.

Officer Malik Grego-Smith was to shoot out the Cadillac’s rear window with a beanbag shotgun, and Hnatuick was to blast pepper spray into the car.

Arevalo was to provide cover with his AR-15 on the left side of Gibson’s car, and officer John Tromboni was set to cover the approaching officers with a standard 12-gauge shotgun.

But before the plan was implemented, Lt. David Dockendorf arrived, took control of the operation and pulled the officers back.

Arevalo, assuming the plan had been called off, asked to provide cover on the right side of the command post, separated from his supervisors by a concrete trash bin enclosure. Hnatuick said yes.

A short time later, Gibson, who had been lying down in his car, sat up and began revving the engine and spinning the wheels. Gibson had done this several times before Dockendorf was on scene.

He reacted by grabbing Grego-Smith and yelling into his radio, “All right, units, we’re moving in. Shoot.”

Dockendorf meant only that Grego-Smith was to shoot the beanbag gun. Many officers later told detectives their radios were not working properly and they never heard Dockendorf. Arevalo refused to speak to detectives after the incident, so it’s unclear what he heard.

A split-second after Grego-Smith shot out the Cadillac’s rear passenger window, Arevalo fired his rifle, hitting Gibson four times. He died at the scene.

Arevalo was not the only officer punished. Dockendorf was to be demoted two ranks, to officer. Hnatuick was given a 40-hour suspension, the department’s maximum punishment short of firing.

All punishments were subject to union grievance procedures.

Arevalo’s firing comes just a week after the Review-Journal reported that Las Vegas police are set to pay $1.5 million to Gibson’s widow. The tentative settlement will go before the department’s Fiscal Affairs Committee on Oct. 28.

If approved, it will be the second million-dollar payout for a police shooting in the past two years and the department’s fourth million-dollar payout overall in the past three years.

The department paid $1.7 million in 2012 to the family of Trevon Cole, an unarmed man killed in a botched drug raid in 2010.

Even if an arbitrator saves Arevalo’s job for the Gibson shooting, Arevalo could also be fired for his separate domestic troubles, according to police sources.

Arevalo was charged with assault and disturbing the peace, both misdemeanors, for a Feb. 2 incident at Canyon Ridge Church with his ex-wife, Catherine Arevalo, and her boyfriend, Steve Delao, according to court documents.

Delao later sought a temporary restraining order against him, telling police Arevalo threatened him.

Gillespie said Arevalo’s domestic situation was something he considered, although it played a small part.

“This was not a big factor in my decision, but the pre-term board also discussed his off-duty incident at the church,” he said.

Arevalo received $133,927.07 in salary and benefits last year while on suspension. His pay for this year was not available.

Contact reporter Mike Blasky at mblasky@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0283. Follow @blasky on Twitter.