Mortgage relief plan in North Las Vegas ignites morality debate

Tonya Hernandez thought a home loan would help build her family’s future.

It ended up pushing her into a financial black hole.

In 2005 she and her husband, Rafael, used equity in their North Las Vegas home to buy two condominiums they could rent out for extra income.

“We were trying to build our retirement,” Hernandez, a social worker, said of the $191,000 loan. “Everyone always says you can’t lose with real estate.”

Everyone was wrong. The economic crash that started in 2008 wiped out trillions of dollars in wealth, including the Hernandez’s home equity.

Now the couple is dreading the arrival of 2015, when the equity loan will reset to an unknown, yet likely higher payment.

They want to negotiate a new mortgage with a principal that reflects the home’s current value of about $80,000 as well as a stable and affordable interest rate.

But they have hit only frustrating dead-ends, in part because the original loan was bundled with others into a security that trades on the global financial markets. The loan servicing company is unable or unwilling to help the couple cut a new deal with the distant, faceless owners of the note.

“I think we have more than paid our fair share on this mortgage,” Hernandez said. “We just want some help.”

That’s why she was excited to learn that North Las Vegas has embraced a controversial program that would use its power of eminent domain to seize underwater mortgages, pay the investors only what the property is now worth and then let other investors write new mortgages with terms more favorable to the homeowners.

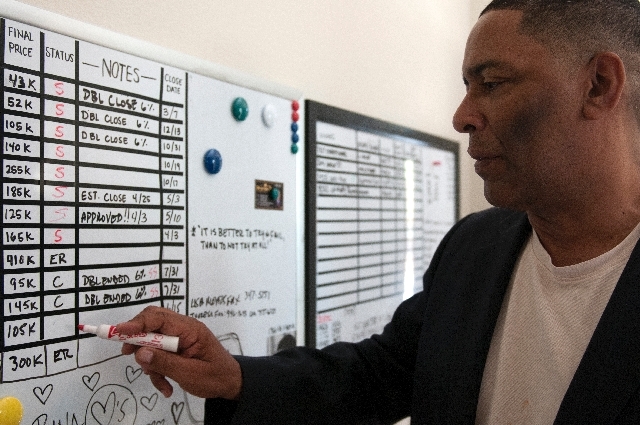

The proposal, crafted by a company called Mortgage Resolutions Partners, has packed City Council meetings and divided a community devastated by unemployment, foreclosures and plunging property values.

It’s a gambit born of desperation and a concept not yet proven viable anywhere. Its legality is being hotly debated, and has already prompted a lawsuit that is likely just the beginning of a long court fight.

Opponents say cash-strapped North Las Vegas risks legal battles it can’t afford and reduced access to affordable mortgages for the entire community should the use of eminent domain cause lenders to deem the city a dangerous place to make loans.

But by merely voting 4-1 to keep studying the idea and reconsider it in August, the North Las Vegas City Council is forcing members of the community to talk openly about who is to blame for the mortgage lending catastrophe and who should bear the cost of cleaning it up.

“What you have is people who grew more frustrated, people who gave up, people who lost all faith in the system,” said Councilwoman Anita Wood describing the effect of the housing hangover. “Some kind of modification needs to happen.”

The idea is attracting scrutiny in Washington, D.C., where Rep. Jeb Hensarling, R-Texas, chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, released a draft of a mortgage finance reform bill with a provision aimed at stopping eminent domain-prompted mortgage relief. It would bar federally backed loans in any county where such a proposal is enacted.

If approved, the legislation would punish nearly every home borrower in Clark County should North Las Vegas go forward with the Mortgage Resolution Partners plan.

FALLING HOME VALUES

It’s no surprise that North Las Vegas would emerge as a target for Mortgage Resolution Partners’ proposal to leverage one of government’s most-feared powers — to take private property for the public’s benefit.

The company has pitched the idea in some of the nation’s hardest-hit areas.

In California, San Bernardino County and the cities of Richmond and Sacramento have considered the idea. The Richmond City Council voted 6-1 in June to be what Mayor Gayle McLaughlin called “a model for other cities.” Others, including San Bernardino County, rejected it after deciding it was too risky.

If anything, North Las Vegas is in more dire economic straits than other communities approached with the idea.

From January 2007 to January 2012, the median home price in the North Las Vegas area fell from $260,000 to $84,000, according to data from SalesTraq. Moreover, residents of the working-class city were hit hard by a recession that erased hospitality and construction jobs.

Even opponents of the Mortgage Resolution Partners proposal, such as real estate professional Gregory Smith, a plaintiff in a lawsuit against the plan, acknowledge the toll.

Smith had a front-row seat to the crash, having paid $350,000 for a house he was forced to sell for $120,000.

“You could see the despair on the face of the wife sitting at the table in the kitchen while people are traipsing through her house,” he said, describing real estate agents showing homes.

The despair didn’t stop at the kitchen table. Once-proud homeowners simply abandoned houses. Yards went untended, blight spread.

“Every homeowner that loses their home, that is a family that is displaced, that is a home that ends up maybe affecting a neighborhood,” former Mayor Shari Buck said. “It does affect the city in quality of life issues and families that we care about.”

Others, like the Hernandezes, held on, stuck with houses worth far less than their mortgage and unable to negotiate better terms with lenders. Many complain they have a hard time getting consistent and conclusive responses from lenders and servicers to questions about renegotiation, let alone a yes or no answer on a new, lower-cost mortgage.

“We’ve seen cases where you have a widow whose husband has died fax the death certificate six times and the servicer calls the next week asking to speak with him,” said Barbara Buckley, a former Assembly speaker and executive director of the Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada. “The runaround some of these servicers use; it is no wonder homeowners are frustrated.”

CITY WOULD ACQUIRE LOANS

Mortgage Resolution Partners is offering what sounds like an easy way to cut through that frustration, resentment and helplessness without the added trauma of foreclosure, bankruptcy and home loss.

Under the proposal, city officials could negotiate to buy notes on targeted, underwater homes at what they believe to be fair value, using the governmental power of eminent domain to acquire the loan from a holder who doesn’t want to sell.

The city would then agree to accept lower-than-face value repayment from the current residents, assuming they could qualify for a new loan. The company would make $4,500 per successful transaction and investors who front the money for the city to pay the original noteholder would be repaid at a profit.

New lenders, likely offering loans backed by government supported entities such as Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac or the Federal Housing Administration, would step in to provide homeowners long-term financing under friendlier terms.

The community would benefit as fewer residents would be struggling under the weight of underwater loans or be pushed out of their houses through foreclosure.

The fee would cover the cost of identifying loans that are good candidates for acquisition, identifying investors willing to finance acquisition by the city, advice on operating the program and a profit. Mortgage Resolution Partners investors and mortgage lenders would also collect interest on the new home loans.

Among the many unknowns is how many homes would actually qualify under the program, if the council decides to implement it. Limiting the program to securitized loans means fewer than 5,000 loans in North Las Vegas would likely qualify.

Securitized loans are targeted, Mortgage Resolution Partners said, because they tend to be the most exotic lending products, characterized by adjustable interest rates, pick-your-payment plans and negative amortization loans, and most at risk of default. Because they have been bundled and sold to distant investors with servicers hired to manage them, they are more complicated for borrowers to renegotiate.

Backers of the proposal say it’s a win for everyone.

“What you have done is turn somebody who is essentially at a very high risk of foreclosure and being ousted from their home into exactly what they want to be, which is a sound, stable home-owning member of the community,” said Byron Georgiou, one of the MRP investors. “Why would we want to continue to permit foreclosures to continue to decimate our community?”

In meetings Mortgage Resolution Partners characterize the proposal as “pre-packaged eminent domain” in which all the parties have agreed on the less-than-face value sale but the judicial action is needed to jump-start the process.

EMINENT DOMAIN

Given the vehement opposition to the idea and serious questions about its legality, it appears doubtful note holders would accept lower payoffs as readily as Mortgage Resolution Partners suggests.

The most controversial element is the leveraging of the city’s power of eminent domain, which governments typically reserve for acquiring property to build roads, bridges or other public works.

In short, eminent domain is the term for the government’s taking of property from a private owner for something determined to be in the best interest of the broader community. The government must pay the owner, but amounts and methods can differ from one state to another. Nevada law requires “just compensation” for the property owner.

That, according to attorney Kermitt Waters, one of Nevada’s most prominent experts on eminent domain, means paying owners enough to be in the same financial position had the action never occurred.

“The concept of eminent domain is an awesome power of the government,” Waters said. “It is an involuntary sale, is what it is.”

Waters favors aid for underwater homeowners and blames financial titans for contributing to the housing bubble and crash, but he also questions whether Mortgage Resolution Partners’ proposal is legal.

He said the city must prove in court that the unprecedented action of seizing underwater loans is in the public interest and would have to show the compensation paid to the note holders is just.

Those rulings could be perilous for the city.

If the court decides the taking is appropriate — a steep argument in its own right — but orders the city to pay more, the cost of the program might make it unfeasible.

Waters also said many mortgages make borrowers personally responsible for deficiencies, which means lenders or note holders could pursue the owner even if the city voids the original mortgage.

And even if lenders don’t pursue the deficiency, the borrower could be liable for a big tax bill on the amount if an exemption that expires at the end of this year isn’t renewed, Waters said.

“It has got so many problems to it, I don’t know how it is going to work out.”

Unlike Waters, who said he supports the concept of providing relief to underwater homeowners, others say the government has already interfered too much in the financial marketplace and the MRP scheme would only make matters worse.

Bill Uffelman of the Nevada Bankers Association said such a broad use of eminent domain would be unconstitutional. He noted that well-intended changes to Nevada law to crack down on bad banking practices have already exacerbated housing-related economic woes.

“We’re kind of in the mode in Nevada that we have to protect people from the downside of their decisions but they are the only ones who benefit from the upside,” he said.

The result, he said, is a buildup of people living in homes they can’t pay for and a shortage of inventory for people looking to get a home of their own.

Had the market been allowed to run its course, people would have refinanced or moved out of homes they couldn’t afford, he said. And those who can keep making payments would eventually benefit when economic recovery pushes housing prices high enough to meet or exceed their debt.

“It is ironic all the things we have done to protect people when in reality passage of time heals all wounds,” Uffelman said.

In testimony representatives of both the Greater Las Vegas Association of Realtors and Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association said enacting such a program would reduce access to credit for future borrowers and harm people who invest in housing finance, including retirement funds.

“In our view, the long-term costs and risks of an eminent domain proposal far outweigh any purported short-term benefits,” Tim Cameron of the securities association testified.

Felix Salmon, who writes a finance blog for Reuters News Service, raises yet another question about the Mortgage Resolution Partners’ idea.

In a post last month Salmon wrote that the company stands to make a disproportionate share of the profit, considering the enterprise rests on the power of the government to do the heavy lifting.

“The real value is added by the use of eminent domain to buy the liens, and it’s the municipal government, rather than MRP, which has that power,” Salmon wrote. “So if anybody makes money from using eminent domain, it should be taxpayers: not some private-sector middleman.”

For Smith, the real estate professional and lifelong Southern Nevadan who is the plaintiff in the Greater Las Vegas Association of Realtors-backed lawsuit against the plan, it is a question of fairness.

“They made a deal,” Smith said of underwater borrowers. Using government force to undo bad loans, he said, “flies directly in the face of personal freedom and it is allowing government to come in for you and decide what is best for you.”

PROTECTING HOMEOWNERS

Mortgage Resolution Partners backers say they’ve heard the critics and are prepared to defend the program in court.

They say opposition is being stoked by a financial industry loathe to accept solutions imposed by others but willing to stoke illogical fears of eminent domain.

“They are the ones trying to make money kicking people out of their houses,” said Mortgage Resolution Partners attorney John Vlahoplus. “The system is broken. It was not designed for this kind of a meltdown. The servicers have no incentive to fix the loan. They make their money from the late fees.”

Others who have studied the economic damage of the home lending and debt crisis say there is truth to the suggestion the finance industry is simultaneously opposing programs that could relieve borrowers of excessive debt while profiting from policies that make it hard for homeowners to find their own path out of the problem.

They cite policies that tilt the balance of home loan agreements in favor of lenders at the expense of borrowers.

Some of those include bankruptcy law that prohibits judges from writing down the principal of the loan on a debtor’s primary residence, even though so-called “cram downs” are legal for debt on vehicles, vacation homes and other purchases.

Another weight tilting the scale against homeowners is the requirement lenders sometimes insert into loans that forbid buyers in a short sale to allow the previous owner to occupy the property.

Brent T. White, a University of Arizona law professor, said such punitive policies force borrowers to behave to a standard to which the finance industry wouldn’t hold itself.

White said communities should make decisions about how to deal with distressed homeowners based on what’s best for their own constituents, not back end investors who bought bundled mortgages on financial markets.

“It is really about distributional issues, who bears the losses,” White said. “Banks will make every argument they can to make sure those losses fall on individuals and not on financial institutions.”

Since voting in June to keep studying the idea, elections have replaced two council members, including the mayor, which adds another layer of political uncertainty to the issue.

For Hernandez, whose job as a social worker has put her in contact with kids who have been uprooted when their parents couldn’t afford to stay in their home, arguments about the law and economics are eclipsed by a desire to protect her son from the same fate.

She says kids are more likely to thrive in a stable environment, and sudden moves or a sense of insecurity can lead to anxiety, bad behavior and poor performance in school.

“I don’t want to do that to my son,” she said. “That is why I am fighting so hard to keep my home.”

Contact reporter Benjamin Spillman at

bspillman@ reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0285.

Draining underwater houses: North Las Vegas is working with Mortgage Resolution Partners to use eminent domain to seize underwater mortgages to assist homeowners.