Filipino-American veterans in Nevada fight for benefits

At 99 years old and tethered to an oxygen tank, Silverio Cuaresma hardly fits the image of a poster child.

Yet, the Filipino-American Veterans of Nevada are hoping that he'll anchor their campaign. The group wants to present President Barack Obama a petition when he visits Las Vegas today.

The petition, with more than 500 signatures, calls for an executive order to compel the Department of Veterans Affairs to grant each of these World War II veterans who are U.S. citizens a one-time, $15,000 benefit as promised under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Others still living in the Philippines could receive $9,000.

Cuaresma was a Philippine guerrilla intelligence officer who served under famous U.S. Army cavalry Maj. Edwin Ramsey and led raids that killed many Japanese Imperial Army soldiers in central Luzon. Cuaresma is currently midstride in appealing the VA's denial of his benefit claim.

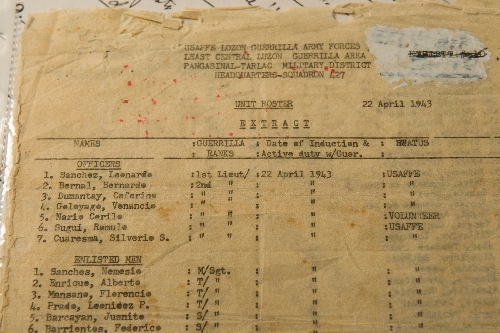

Although he met the Feb. 16, 2010, filing deadline and has authentic, yellowed, typewritten papers documenting his service under Ramsey's command as well as a signed affidavit by Ramsey himself, the VA rejected his claim. His case is not unlike more than 24,000 other Philippine-American veterans whose claims have been denied.

The reason: The VA's Manila office and the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis don't recognize the guerrilla rosters and other Philippine military papers they submitted for their claims.

"I feel very sad," Cuaresma said Thursday, sitting at the dining room table of his daughter's house on the Las Vegas Valley's west side.

"Despite my bravery and fighting for the cause of peace, freedom and democracy for the United States and the American people, they do not recognize me as one of the defenders. It's bad. I am a hero of World War II."

BATTLE FOR BENEFITS

Cuaresma's legal battle with the VA began in 2001 to establish his status as a veteran. That case and the ongoing appeal for compensation under the Recovery Act has lasted much longer than the four years U.S. forces fought in World War II.

"They are waiting for me to die," he said. "Maybe they don't like me to win, but I keep on trying."

A VA spokesman in Los Angeles, Dave Bayard, said Friday the agency's staff will research Cuaresma's case for releasing as much information about it that is allowed without a waiver under the VA's privacy guidelines.

When the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act passed, the number of eligible World War II Filipino veterans was estimated to be 18,000 out of more than 200,000 who served during the war.

As of Oct. 13, the VA had granted 9,334 claims for $9,000 each and 9,165 for $15,000 each, bringing the combined payouts to more than $221 million.

That's more than the $198 million that was allocated for the Filipino Veterans Equity Compensation Fund, but $44 million less than what was made available after Obama approved a supplemental appropriation of $67 million for the fund in July 2010.

Should Cuaresma die before the issue is resolved, his wife, Felicidad, 91, would be entitled to the $15,000 as his surviving spouse if the VA acknowledges his service under Ramsey.

LAST CAvalRY CHARGE

Military historians credit Ramsey with leading the last horse cavalry charge in U.S. history on Jan. 16, 1942, as Troop E of the 26th Cavalry Regiment headed toward the village of Morong. Japanese forces had landed at Lingayen Gulf, outnumbering Americans and Philippines who made a retreat into Bataan.

Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, the North Luzon commander, ordered Ramsey, a first lieutenant at the time, to take the lead into Morong.

Reached Friday at his home in Los Angeles, retired Lt. Col. Ramsey, 94, said he led three mounted squadrons into the jungle. With pistols ablaze they charged through the village shooting Japanese soldiers who had just crossed a river.

"We had four or five casualties," he said, adding that he was wounded by a mortar shell that killed his horse "right next to me. We were fighting on foot, then."

"We fought all the way back into Bataan as a mounted cavalry unit. Once we got into Bataan, the horses were taken away and slaughtered for food, because we were all starving."

With the surrender of Bataan imminent, Ramsey and another officer opted not to surrender and instead fled.

"We crawled up the top of the mountain and over the other side and escaped," he said.

Filipinos helped conceal him while he organized a small guerrilla force that grew to 38,000 enlisted men and 3,000 officers under his command.

"You can never give enough credit to what the Filipinos did," said Ramsey, who has appeared before Congress and federal courts to testify on behalf of Philippine-American veterans.

"Every time this subject has come up over the years, I have had the same problem convincing people that these guys were working for us and, if they hadn't, it could have cost us a hell of a lot more lives," Ramsey said. "I think their service to the United States should be approved. I think it's a damn shame it's taken so long for things like that to get taken care of."

GUERRILLA FIGHTERS

On April 22, 1943, Cuaresma was appointed second lieutenant "in the field by order of Edwin P. Ramsey, major, U.S. Army commanding."

The fragile, yellow document that Cuaresma's family keeps in a plastic sheath is certified by a Philippine infantry captain, Candido Prado.

It states that Cuaresma was an intelligence officer for Squadron 427 of the First Provisional Regiment of Tarlac of the East Central Luzon Guerrilla Area.

A roster that bears the same date, April 22, 1943, for the Pangasinan-Tarlac Military District, names "Cuaresma, Silverio S., 2nd Lt., USAFFE," as the No. 7 officer on a list of 85 soldiers.

From then until Gen. Douglas MacArthur returned to liberate the Philippines on Oct. 20, 1944, and for nearly a year afterward, Cuaresma said he led up to 40 guerrillas in raids that killed scores of Japanese troops.

They would creep up on Japanese strongholds at night and attack their camps with grenades.

"I told my men to hold five grenades each and when they were 20 meters away to throw one grenade at a time, every two seconds," he recalled. "They were all dead when the last grenade was thrown."

For that particular attack, he was awarded a commendation for bravery from Prado.

Cuaresma's guerrillas sometimes would set dynamite charges on bridges and hide nearby to detonate them when the enemy crossed.

Cuaresma, born June 19, 1912, was inspired to fight for American troops in his homeland because he had seen how Japanese invaders had abused Philippine men and women.

"It hurt my feelings, the maltreatment of our people," he said.

After the war, he continued to live in the Philippines and worked as a livestock official for the Bureau of Animals.

He moved to New York in 1984 to live with one of his sons. He became a U.S. citizen five years later.

Luke Perry, outreach coordinator for the nonprofit, Filipino-American Veterans of Nevada, believes Cuaresma is the oldest Philippine veteran living in Nevada.

Perry and group leader Caesar Elpidio hope the Obama administration will accept their petition.

Perry said the emergency executive order is needed to compensate veterans like Cuaresma and "correct World War II history."

Rep. Joe Heck, R-Nev., said in a statement Friday that he intends to do "everything in my power to ensure these heroes receive the benefits they were promised."

"It's unconscionable that these documented American veterans are being treated the way they are."

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers @reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.