Teachers leverage children’s interest in space

Here's one way to prompt what Doug Lombardi promises will be a "very spirited discussion" among middle school kids.

Mention Pluto.

Kids still are "very angry about Pluto's demotion to a dwarf planet," explains Lombardi, an area science educator and past president of the Southern Nevada Science Teachers Association.

Beyond the admirable empathy for the underdog the kids' ire represents, it's also evidence that, four decades after man landed on the moon, kids still possess an innate fascination with space and space exploration.

Almost 50 years ago, on May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy announced to a joint session of Congress his goal of sending an American to the moon before the end of the decade. On July 20, 1969, Kennedy's dream was achieved when Neil Armstrong stepped onto the lunar surface.

Since then, the United States' space exploration efforts have shifted largely to unmanned projects and the space shuttle program. Now, as the latter winds down and the U.S. transitions to a slate of less gee-whizzy unmanned programs, the question becomes: How do you continue to keep kids interested in space exploration?

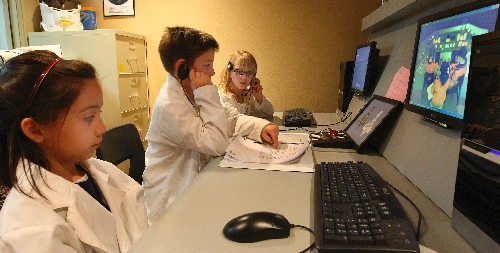

It's no problem at Lamping Elementary School, where students learn about space exploration not just from the impressive displays in the school's William McCool Science Center but by playing the roles of astronaut and mission controller in the school's space shuttle simulator.

"The space program has always seemed pretty cool to me," says fifth-grader Simon Blackhurst, who on this day is serving as a shuttle astronaut.

"A lot of people at this school do like space," agrees fellow astronaut and fifth-grader Max Czerwinski.

Fifth-grader Faith Schuck, who's serving as a mission controller today, not only is interested in space, but expects to remain interested in space and space exploration even after she leaves Lamping. And, she says, she's even thinking of making science a career.

Yet, Schuck and her fellow student/controllers also agree that they may not be as smitten with space if they hadn't been exposed to Lamping's science- and space-oriented programs.

Lamping's science center is named after U.S. Navy Cmdr. William McCool, an astronaut who died in 2003 when the shuttle Columbia disintegrated during re-entry. His parents, Barry and Audrey McCool, lived in the Lamping neighborhood and, with private donations from the community, built the center to encourage students' study in space and the sciences. (The center also includes an observatory, a weather station, a simulated archaeology dig area and other hands-on science education tools.)

Principal Robert Solomon says such tools, coupled with enthusiastic teachers, can help to kick-start kids' interest in science as early as kindergarten, and even prompt them to think about studying for a career in the sciences.

Children do seem to possess a natural curiosity about their world that meshes perfectly with science education, Solomon notes. "I think there's a natural interest (among kids) in what you can't touch and feel yourself."

Dale Etheridge, director of the College of Southern Nevada's planetarium, agrees. Young planetariumgoers, Etheridge says, love discovering that "we're just this one little blue ball in space and all sorts of other things are going on in the universe. They find that exciting."

In fact, Etheridge says, "we see our role is more motivation than instruction." It's great if kids leave the planetarium with hard facts, he says, but the more important goal is to "get them excited and help stimulate their excitement about science."

Rob Lambert, president of the Las Vegas Astronomical Society, conducts educational outreach programs for both school students and youth groups throughout the valley and notes that "middle school seems to be where most of the interest is."

For example, during one event for valley Cub Scouts, Lambert says about 350 children visited his astronomy station over the course of a single weekend.

For these kids' parents or grandparents, who grew up during the space race years of the '60s and early '70s, a fascination with, or at least an exposure to, space and space exploration was pretty much a given. Lombardi, a facilitator with the Southern Nevada Regional Professional Development Program and a former classroom science teacher, was about 6 when he saw the Apollo 11 moon landing.

Lombardi says he's "absolutely sure" that his lifelong interest in space and science -- before becoming a science teacher, he even worked for a time as a research scientist and engineer -- can be traced back to following the space program as a kid.

Even though today's kids have nothing as dramatic as the moon landing to ignite their imagination, "I think kids are really intrinsically still interested in space," Lombardi says.

But, he says, the lack of a dramatic, high-profile effort such as the Apollo program does make it more challenging to nurture that interest.

"I don't think we have that feeling anymore, and it's probably due to some degree that we're not exploring the moon," he says. "The shuttle program has been fantastic, I don't want to discount that. But it's not the same as going someplace we haven't gone before."

Another hurdle, says Lamping science teacher Christa May, is the relative lack of press the space program receives today.

"I think a big part of it is the lack of enthusiasm that comes from the press," she says. "I talk to kids when we're doing survey lessons and say. 'Do you guys know who's in space right now?' 'No way. People don't live in space.' "

Now, as then, getting kids interested in space and science hinges on finding ways to fuel their inherent love of discovery. Once, while attending his grandson's birthday party at a family pizza parlor, Lambert stepped outside to watch the International Space Station pass overhead.

"I stepped outside for a few minutes to look up in the sky," he says. "As people were coming into Chuck E. Cheese, they said, 'What are you doing?' I told them the International Space Station is passing and I just wanted to catch it. I said: 'It's going to be five seconds. Look over the top of this building and you'll see a bright dot becoming brighter and brighter coming across the sky.'

"So, at one time, I had 15 people standing around me in front of Chuck E. Cheese, looking at the space station."

Lambert says he sees similar interest at the society's monthly public stargazing events, where attendees always include a sizable universe of kids.

"What's really fun is when you are doing one of these star parties and, say, we've got Saturn in the eyepiece, and somebody has never looked through a telescope, especially little kids," Lambert says.

"They walk up and look, and you tell them, 'You're seeing Saturn and its rings.' You'll get, 'No way!' And that makes it worth it."

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@ reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280.