Cosmetic surgeons devote more time to patient ‘redos’

As soon as Michelle Taylor looked in the mirror, she knew something was wrong. She now viewed the world through two narrow slits, and the area beneath one of her eyes had turned blue.

But the dermatologist who had injected the filler into a hollowness under her eyelids and smoothed out fat deposits said it was just a minor matter of healing time before her skin took on a natural hue again and the swelling went down.

Two years later the discoloration and puffiness were still there.

"I've been pretty upset," said Taylor, who recently traveled from Montana to Las Vegas to see if a cosmetic surgeon could undo what had been done back home. "I had been wearing sunglasses even when there wasn't any sun."

As it turned out, Dr. Shoib Myint was able to reverse the condition under her left eye, and the other eye will be done soon.

"The filler had been put in too close to the surface of the skin," Myint said recently in his office off West Sahara Avenue.

"She's lucky that the filler that had been used was one I was able to flush out. Too often people who don't know what they're doing will use a filler that can't be reversed. In rare cases I've seen, people have lost their vision because of the way the filler is placed."

As the number of people electing to have cosmetic procedures continues to rise across the country, the number of corrective revisions, or "redos" as they are often called, appears to be increasing at a rate that is significant enough to cause concern among medical practitioners.

"Sometimes what has been done to patients actually astounds me," said Dr. Michael Edwards, a Las Vegas plastic surgeon who is a spokesman for the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. "Unfortunately, people will go out and simply price shop for surgery, and then the next thing you know they're spending two to three times more for revision surgery."

Some 17 million cosmetic procedures were performed in the United States last year, but no one knows how many were redos.

While anecdotal evidence tends to support the notion that more redos are being done -- top plastic and cosmetic surgeons throughout the United States believe it is -- it is impossible to know an actual number, because major medical associations don't keep statistics on revision surgery.

New York plastic surgeon Andrew Jacono , whose expertise is often sought in the most difficult facial cosmetic surgery revision cases in the country, dedicates 35 percent of his practice to surgery on patients unhappy with results delivered by other doctors.

Jacono estimates that 10 percent of cosmetic surgeries in the United States are redos.

If Jacono's estimate is on the mark, that would mean 1.7 million revision cosmetic surgeries are done each year.

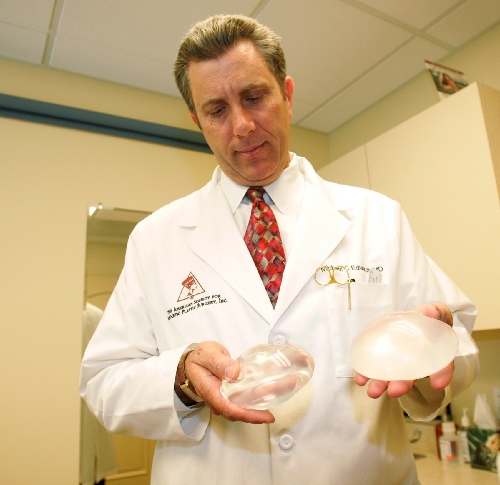

Edwards, who stressed that even the best surgeons encounter complications in their work, now devotes more than half of his practice to revision surgery, largely to breast implant procedures.

He said a number of those are necessary because implants simply wear out.

Las Vegas plastic surgeon Stephen Gordon also noted that breast implants are expected to need "maintenance" every 10 years.

It is actually very possible for a woman who gets her first breast implants in her 20s to need five more implantations in her lifetime, according to data released by implant manufacturers.

One woman who had breast implants originally done on the East Coast and who recently had revision surgery done in Las Vegas said she had wanted to do it for years but the cost had held her back.

"My nipples weren't the same height, and one breast was firm and the other squishy," the woman said.

A woman from Canada also came to Las Vegas for a redo of her breast implants. A redo by the original surgeon still had left her unsatisfied.

"My breasts were too far under my arms, so I didn't have any cleavage," she said.

The total cost of her three surgeries was around $20,000, she said.

Both of the breast implant revision surgery patients had their redos done by Las Vegas cosmetic surgeon Samir Pancholi.

Though they asked for anonymity because they did not want people to know they had breast augmentation work done, both women said they are now happy with their revision procedures.

"Dr. Pancholi actually listened to what I wanted," the Canadian woman said.

Pancholi, who is a spokesman for the American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery, said it is not uncommon for revision surgery to cost more, because "it is more difficult than the original surgery."

"Often, you have to deal with a lot of scar tissue," he said.

Myint said has no doubt that Hollywood led the surge in plastic surgery throughout the country as Americans learned through the media that many of their favorite celebrities were players in the nip-tuck world.

Celebrities also have led the charge in having second thoughts about what they have had done, he said. Not all of them can have redos.

For instance, Priscilla Presley, former wife of Elvis, admits that a fake doctor, who went to prison for his unlicensed injections on several people, injected her with the same industrial silicone used for greasing automobiles. Her face now is cratered and lumpy.

"Unfortunately, there's nothing that can be done for that," Myint said. "You have to be very careful with the unscrupulous. I have had to try and work with a patient who also had industrial grade silicone injected. There was nothing I could do. I said the only thing that could be done is a full reconstruction, and I didn't think she would be happy with the looks of that either."

Myint's successful cosmetic facial surgery practice has earned him a spot as a regular contributor to the popular website Awfulplasticsurgery.com, which is marketed as having "the best of the worst celebrity plastic surgery."

"Let's face it," he said. "People are interested in celebrities. I hope I can help them learn something from my input."

Myint said Angelina Jolie-inspired lip injections have resulted in far too many people taking away from their natural beauty.

On the awful plastic surgery website, he wrote about porn actress Jenna Jameson's lip injections:

"Jenna clearly has the classic trout pout lips. She has broken the 70 percent anatomical rule. Not only are her upper lips larger than her lower lips (too aggressive augmentation with either filler or surgery near the wet/dry junction), but there is also loss of any evidence of a vermilion border. She also has no tapered look to her upper and lower lips. This sausage-like appearance indicates once again an aggressive approach along the outer corners of the lip."

Depending on the filler used, Myint said sausage lips often can be overcome.

If people are partly educated about plastic surgery by the kind of website that shares Myint's observations, it is still difficult for the would-be patient to know which doctor's work is the most successful.

Physicians are not required to disclose data about revisions of their work; nor do they have an incentive to do so.

Patients, well aware that they have chosen of their own free will to take part in elective procedures, are reluctant to file lawsuits that could give consumers a better sense of whose work frequently needs revision.

Taylor said most patients sign paperwork before procedures which reminds them that a good outcome is not guaranteed.

"You have to remember that beauty is subjective," she said.

A patient who recently contacted Edwards for breast implant revision surgery said no matter how much homework you do you still have to "make a leap of faith."

"Doctors will show you before and after pictures that have different lighting and might not even be their patients," said the woman, who spoke only on condition of anonymity. "Dr. Edwards looked into the background of my former doctor back East and found he was an emergency room doctor advertising himself as a cosmetic surgeon. You don't think a doctor would lie, but they do. There's just too much money involved. I have a hard time trusting them. They give you references of other patients, but you know they won't give you a reference of someone they screwed up."

Dr. William Zamboni, chief of plastic surgery with the University of Nevada School of Medicine, said consumers should always check on a physician's board certification to see if there has been formal training in plastic surgery.

A spokesman for the American Society of Plastic Surgery, Zamboni said the cases of revision plastic surgery that he handles generally involve medical tourism.

He said some Nevadans go to Mexico or Costa Rica because of price but then are dissatisfied with the results.

"Some of those surgeons are simply not qualified to do plastic surgery," Zamboni said. "And then a patient comes to me desperate for help and ends up paying double or triple what he would have paid in the first place."

Local physicians say it is important to remember that redos don't always mean there has been a botched plastic surgery.

It is not unusual for some people to have several surgeries on the same feature -- much like Michael Jackson did with his nose -- as they strive to find what they believe to be the perfect look.

"If you do it too much, though, it can have serious consequences, just as it did with Michael," Gordon said. "A surgeon might want to refuse someone, but it's hard when they know the patient is just going to go down the street and get it done."

Myint said surgeons have to constantly be on the lookout for individuals who want work done who suffer from a psychological disorder known as body dysmorphic disorder.

"No matter what you do they won't be happy," Myint said. "Those people see flaws that do not exist."

Neither Zamboni nor Gordon said they have to do much revision surgery on the work of local plastic or cosmetic surgeons.

Gordon said the revision surgery he often does is the result of someone wanting to maintain the look they received as a result of surgery years before.

"In this economy," he said, "people aren't getting as much new work, but they are maintaining what they have."

Zamboni said the present economy also makes it unlikely that people will go to doctors who take a few weekend courses and say they are plastic surgeons.

"As tough as times are, I think those doctors have been weeded out here," he said. "People are smart enough to want the most for their money."

That's a far cry from 1996, when the image of plastic surgery in Las Vegas was at its nadir after 24-year-old Maria Wehr died after receiving a nose job at the office of Las Vegas plastic surgeon Alban Miller Jr.

While receiving anesthesia from Miller and an untrained assistant, she went into full respiratory arrest. Before she died, she lived for 55 days at University Medical Center in what authorities called "a chronic vegetative state.

The Nevada State Board of Medical Examiners placed Miller on probation for three years and ordered him to do surgery only under the supervision of an anesthesiologist in a hospital or in an approved clinic setting.

Southern Nevadans are largely happy with cosmetic surgery done in Las Vegas, where statistics show that the most popular procedure is breast augmentation.

A 2004 local survey on health care found that plastic surgery was the only medical specialty that the majority of residents judged to be among the best in the nation.

A bartender whose breast implants were sagging with age just had her breasts redone by Pancholi. Happy with his work, she believes she knows why the local cosmetic surgery is done at a high level of expertise in Southern Nevada.

"Every woman I know has to have it in Las Vegas for her job," she said. "You're simply not going to get tips from men if you don't have good-size breasts for them to look at. So the plastic surgeons get a lot of practice here."

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.

Related Story: Plastic surgery patients urged to find doctors board certified