Gaming’s past, seen by someone who lived it

Bob Miller didn’t think much of the casino concept proposed to his father.

The year was 1968. Miller was preparing to attend Loyola Law School in Los Angeles.

Miller’s father, casino executive Ross Miller, allowed “a short, portly gentleman” to join the family’s traditional Sunday night dinner at the Riviera’s Hickory Room.

Bob Miller considered the man’s casino plans “utterly ridiculous.”

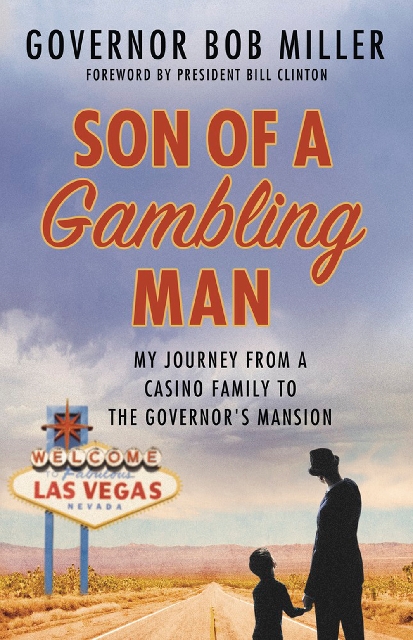

“My father, for one of the only times I could remember, solicited my opinion about business,” Miller wrote in his newly released autobiography, “Son of a Gambling Man,” which chronicles his rise to become Nevada’s longest-serving governor.

“That’s the stupidest idea I’ve heard in my life,” Bob Miller told his father, which led to the next line in the book: “Bob Miller, gaming visionary.”

The rotund gentleman was legendary casino developer Jay Sarno, who built Caesars Palace. Sarno, who was considered a frontman for organized crime’s control on Las Vegas through the 1970s, was pitching the idea for Circus Circus.

Ross Miller didn’t listen to his son and went with his instincts. Sarno’s pitch led him to become an original investor in the casino.

“The funny thing is when you look up Circus Circus on the Internet or Wikipedia, there is no mention of my father,” Bob Miller said last week.

Even before Circus-Circus, the elder Miller spent more than a decade as a minority owner and operator of the Riviera before selling in 1968.

Ross Miller, an illegal- bookmaker from Chicago with ties to organized crime, was a Las Vegas success story. His history, however, nearly derailed his son’s political career.

Bob Miller spent years deflecting ties to his father’s past.

Not anymore.

In “Son of a Gambling Man,” Bob Miller details his father’s gaming career, which began behind the shadows of an illegal bookie joint and burlesque club in Chicago but migrated out to the open spaces of fledgling Las Vegas.

Bob Miller recalls his father as “a classic example of what Vegas gaming executives were back in those days.” They may have had nefarious ties elsewhere, but Nevada was the state of “second-chance opportunities.”

Ross Miller owned and operated three Strip casinos. But he also had relationships with organized crime figures, such as Chicago mobster Gus Greenbaum, an investor in the Riviera, and Allen Dorfman, who arranged hotel-casino loans from the Teamsters’ Central States Pension Fund. Ross Miller’s business partner at the Slots-A-Fun was Carl Thomas, who went to federal prison for skimming at the Tropicana.

“My father wasn’t a gangster, but because of the nature of his business, he moved in their world,” Miller wrote.

One day, a teenage Bob Miller came home to find his father visiting with Jimmy Hoffa, president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. He didn’t eavesdrop on their conversation.

Ross Miller also was a pillar of the Las Vegas community. He was a founding member of the Las Vegas Country Club and was close friends with Gov. Grant Sawyer and Clark County Sheriff Ralph Lamb.

In 1967, Ross Miller was one of several individuals indicted by a federal grand jury on charges of skimming from the Riviera’s casino. The charges were later dismissed.

“I was, of course, enormously relieved,” Miller wrote. “I never discussed this matter with my father. This probably seems a bit strange, but I knew the sensitive conversations with my dad were only initiated by him and not by me. He never brought it up.”

Ross Miller, who died in 1975, didn’t want his son to go into gaming.

Instead, Bob Miller embarked on careers as a lawyer, prosecutor, justice of the peace, district attorney, lieutenant governor and eventually Nevada governor from 1989 to 1999.

Political opponents used Miller’s family history against him throughout his career.

In 1988, incumbent Republican U.S. Sen. Chic Hecht made Ross Miller’s organized crime ties a campaign issue against his Democratic opponent, Gov. Richard Bryan. Then-Lt. Gov. Bob Miller would become acting governor if Bryan won.

Statewide news conferences with law enforcement officials quelled the storm.

“Bob Miller is no more an associate of organized crime than the pope,” Clark County Sheriff John Moran proclaimed.

Today, we seem to celebrate gaming’s past ties to organized crime. Las Vegas is home to the downtown Mob Museum and a casino-housed attraction dedicated to the city’s organized crime past. Three-term ex-Las Vegas Mayor Oscar Goodman was once the mob’s attorney.

Miller became acting governor in 1989, the same year The Mirage opened as the Strip’s first new hotel-casino in 15 years. Over his decade in the governor’s office, the Strip boomed and resorts such as Excalibur, MGM Grand, Treasure Island, Paris Las Vegas, The Venetian and Bellagio were built. Caesars Palace brought the Forum Shops to the Strip.

“I would deal with issues against the backdrop of the country’s fastest growing state, undergoing a metamorphosis that Ross Miller could not have dreamt of when he came to Nevada almost a half century earlier,” Miller wrote.

Like his father, Miller himself has become a gambling man. Since 2002 he has served on the board of directors of Wynn Resorts Ltd. Miller joined the board of directors of slot machine giant International Game Technology in 2000 and is now the longest-serving member.

For Nevada political junkies, “Son of a Gambling Man” contains hundreds of nuggets.

For those interested in gaming’s past, Bob Miller provides a look at Las Vegas’ history from someone who has lived it.

Howard Stutz’s Inside Gaming column appears Sundays. He can be reached at hstutz@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3871. He blogs at lvrj.com/blogs/stutz. Follow @howardstutz on Twitter.