How many people have owned the Fontainebleau project?

Jeffrey Soffer

Florida developer Jeffrey Soffer announced plans for the Fontainebleau in 2005, the same year he acquired the iconic 1950s-era Fontainebleau hotel in Miami Beach.

He teamed with former casino executive Glenn Schaeffer on the north Strip resort, which at the time was described in news reports as a $1.5 billion, 4,000-room project.

They started construction on the 60-plus-story project in 2007 — the price tag was a reported $2.9 billion by then — and aimed to open in 2009. But the real estate market soon crashed, and the economy went into a freefall.

In spring 2009, the Fontainebleau’s developers sued several banks, alleging the “unscrupulous” lenders backed out of their commitment to finance construction of the resort.

Without the additional funds, the project “cannot be finished and will never open,” the developers warned.

The unfinished resort went bankrupt in mid-2009 — one of countless real estate projects in Southern Nevada to get derailed after the bubble burst.

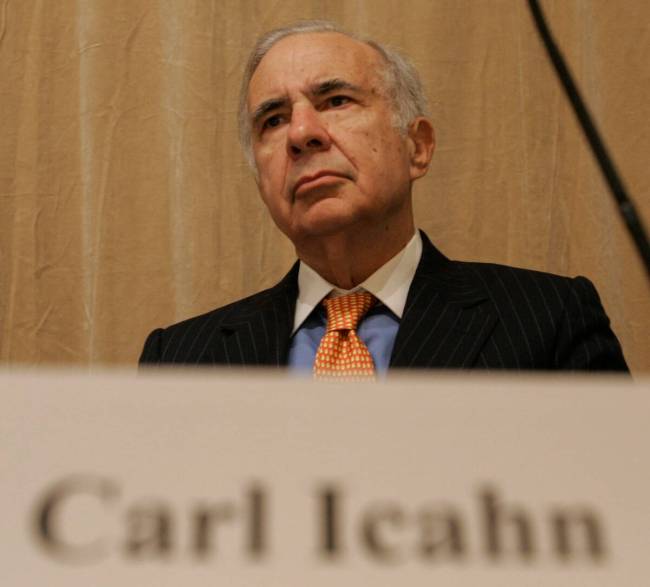

Carl Icahn

Billionaire Carl Icahn purchased the Fontainebleau in early 2010 for around $150 million.

“It’s pretty stormy in Vegas right now,” he said around that time. “We’ve always liked Vegas, but it’s probably overbuilt a bit too much. But that doesn’t mean it will be overbuilt forever. We have hope the sun will come out again.”

Ultimately, Icahn didn’t do much with the blue-tinted high-rise.

Operators of the Plaza, in downtown Las Vegas, acquired furniture, carpeting and wallpaper that had been intended for the Fontainebleau. Years later, Icahn agreed to wrap a rusted section of the unfinished structure to cover the eyesore, according to news reports.

In summer 2017, with Las Vegas’ economy climbing back from the recession, Icahn sold the Fontainebleau for $600 million — quadruple his purchase price.

Steve Witkoff

Developer Steve Witkoff teamed with real estate firm New Valley, a subsidiary of a cigarette maker, to buy the stalled skyscraper from Icahn.

Witkoff did not unveil any detailed plans at first but said the high-rise was “one of the best physical assets in the country” and a “well-designed, structurally sound” project.

In early 2018, Witkoff and hotel giant Marriott International announced the hotel-casino was now called Drew Las Vegas and would feature Edition and JW Marriott brands. He named the property for his son Andrew, who died of an OxyContin overdose in 2011 at age 22.

In an interview with the Las Vegas Review-Journal in spring 2019, Witkoff said he had heard “150 nasty rumors” about the building’s condition before he bought it, including that it was falling down, that copper cables were stolen, and that plumbers poured concrete in the pipes.

In truth, he said, the project was in “exceptional shape.”

He told the Review-Journal in January 2020 that he was close to obtaining a roughly $2 billion construction loan for the Drew. But that March, as Las Vegas rapidly shut down over fears of the coronavirus outbreak, he shelved construction of the project.

Contractors filed liens alleging unpaid bills for their work at the Drew, and several ex-employees sued Witkoff, claiming they were laid off from the project amid the pandemic and weren’t paid what their contracts called for.

In early 2021, Soffer came back and acquired the property through a “deed in lieu of foreclosure.”

Las Vegas real estate broker Michael Parks, a hotel-casino specialist with CBRE Group, said at the time that a deed-in-lieu is typically undertaken because a property is in financial distress and that such transactions are “more prevalent in times of economic turmoil.”

The new owners scooped up the plot with the unfinished high-rise for $350 million.

Jeffrey Soffer (again)

Soffer, chairman and CEO of Fontainebleau Development, teamed with Kansas conglomerate Koch Industries’ real estate wing on the acquisition.

At first, they offered no details on their plans for the site. Then in fall 2021, Soffer renamed the project Fontainebleau Las Vegas, said construction was underway, and penciled its opening for the fourth quarter of 2023.

“It’s kind of a crazy story, but I’m back,” he said at a media event.

He told the Review-Journal that after he reacquired the property, he walked through it for the first time in more than a decade, and it looked like nothing had changed.

“It was just the same way we left it,” he said.

In 2022, his team unveiled plans for the Fontainebleau’s meeting and convention space and high-end shopping area. Workers also put up a billboard for the resort that declared, “Miracles still happen.”

Soffer later unveiled a $2.2 billion construction loan for the megaresort, and then said in September that the Fontainebleau will open Dec. 13 — almost two decades after he first announced the project.

Contact Eli Segall at esegall@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0342.