Man behind major Las Vegas Strip property deals has terminal cancer

Driving along or near the Strip, it’s easy to find properties John Knott was hired to sell.

In just the past few years, he brokered the sales of the Raiders stadium site, the Hard Rock Hotel, the shuttered Lucky Dragon and the former Alon casino site next to Fashion Show mall. He shopped the former Fontainebleau around and, before the economy crashed last decade, sold the Sahara and a tract of land across the street for hundreds of millions of dollars apiece.

On June 7, he sent out an email with the subject line “Retirement Party!” He was inviting people for drinks, but he was really announcing something else: Knott is dying.

Knott, head of CBRE Group’s global gaming group, expects to die this month or next from metastatic pancreatic cancer. He decided to forgo chemotherapy treatment.

“Hopefully, when things get difficult the end will come quickly,” he said in the email.

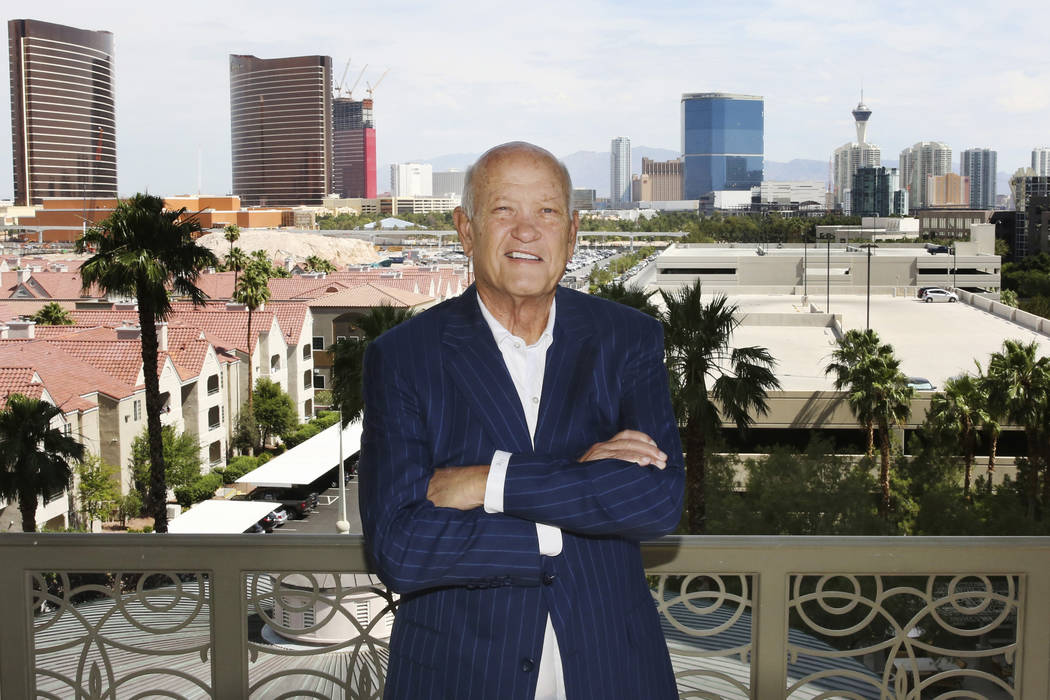

The 62-year-old broker will leave a legacy of high-profile real estate deals. Las Vegas’ economy is dominated by massive hotel-casinos, but only a handful of brokers in town get hired to sell resorts or vacant land on or near Las Vegas Boulevard. Knott and his partner Michael Parks appear the most prolific of the bunch, regularly getting tapped to shop these and other high-priced properties around.

Knott, a father of three girls in their 20s, sat down with the Las Vegas Review-Journal last month, after he announced his diagnosis, and talked about his life, his career and his cancer.

Over the years, he dealt with people like billionaire Carl Icahn and Donald Trump and racked up a lengthy list of real estate transactions that he couldn’t have imagined in his 20s.

“It’s been fabulous, so, no regrets,” he said.

Boiler room

Knott was born in New Jersey and moved to Las Vegas in 1964 at age 7. He went to Western High School, worked in his father’s printing shop, and at 21 had a summer job counting cash from table games at the Sands.

After college, he still worked for his dad’s business. It was like FedEx Office, Knott said, but job orders were run on a press.

He didn’t like collating and stapling, and after a customer came in at 5 p.m. on a Friday, and his dad told him to get the press going and fill the order, Knott decided to move to Los Angeles. He loaded all his belongings into his 1978 Corvette, stayed on a friend’s couch in California, and went to work in a “boiler room” calling people to buy gold, silver and platinum.

He was a guy in a phone room making at least 100 calls a day. The good news, Knott said, was he learned how to sell.

Boom and bust

He spent about nine months in the boiler room. Eventually, with some close friends working in real estate, Knott decided to give that field a try. He was still in his 20s and wanted a flexible schedule that would let him play golf. He also thought he could make a lot of money and didn’t want anyone telling him what to do.

After 10 years with Cushman & Wakefield in Los Angeles he returned to Las Vegas in 1994, months after the Northridge earthquake caused $100,000 in damage to his house. He ran his own firm, Sullivan & Knott, before joining the company now known as CBRE in 1999.

He managed its Las Vegas office but didn’t like overseeing brokers and wasn’t doing any great recruiting. In 2003, he took charge of the firm’s global gaming group. The team was operational, he said, but hadn’t had much success.

Las Vegas’ wild real estate bubble was starting to inflate, and like countless others in town, Knott cashed in on the frenzy. In 2007, he sold the Sahara for $345 million to hotel and nightclub operator Sam Nazarian and investment firm Stockbridge. The same year, he sold a 26-acre parcel across the street for $444 million to the casino giant now known as MGM Resorts International.

During the mid-2000s, casino operators bought rivals for billions of dollars, a burst of megaresorts were proposed for the Strip, land values soared, home construction was skyrocketing, and it seemed everyone wanted to build condo towers.

There were also people “who had no money” and were trying to acquire properties to flip for profit, Knott said.

“That’s not a market I’d ever seen,” he said.

Southern Nevada was arguably the hardest-hit area of the country when the economy crashed, and Knott wasn’t spared the carnage.

He had teamed up to acquire the Las Vegas National Golf Course in 2007 and saw its value nosedive. Real estate investments in California and Arizona were wiped out, and his brokerage business dried up. He still had to make a living, so he started appealing property taxes for casino operators.

The economy slowly regained its footing, and Knott’s team booked several sizable deals in recent years.

He sold the vacant former Alon site for $300 million to Wynn Resorts; 62.5 acres of land to the Oakland Raiders for $77.5 million; the Hard Rock Hotel to flamboyant British billionaire Richard Branson and partners for a reported $500 million; and the closed Lucky Dragon for $36 million to Don Ahern, chairman and chief executive of Las Vegas construction-equipment firm Ahern Rentals.

‘I’m good to go’

Last October, Knott was supposed to tour the Lucky Dragon but wasn’t feeling well and called his cardiologist. He ended up getting two stents in his heart.

Doctors also found an abnormality in his abdomen area. In April, he learned he had pancreatic cancer.

Knott said last month that he might live three to six months if he did chemotherapy or perhaps two to four without it. His doctor could treat the nausea from chemo but not the fatigue; as Knott saw it, he didn’t want to live an extra few months having been tired the last several months of his life, saying he’d rather “socialize with my friends and family before I go.”

Knott had a friend who was dying and decided against pain medication. “I’m good to go,” the friend said. “I’m happy with my life.”

Last month, when asked if he feels the same way, Knott said: “Absolutely.”

Contact Eli Segall at esegall@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0342. Follow @eli_segall on Twitter.