Utility aims to salt away solar power

The sun already shines year-round in Nevada.

Now, a California company says it has found a way to harness sunlight around the clock as well, and Nevadans soon could see the resulting solar energy powering their homes.

NV Energy was scheduled to announce today a 25-year agreement to buy power from the Crescent Dunes Solar Energy Project, a plant that SolarReserve plans to build on federal land outside Tonopah, about 175 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

Crescent Dunes will be the nation’s first commercial solar power plant using salt storage to distribute energy after the sun sets, and it will be the second-largest renewable-power source in NV Energy’s fuel portfolio. The power plant will yield enough juice to power 75,000 homes during peak electric use.

The agreement is NV Energy’s largest solar-power purchase agreement. To reach state mandates on renewable-energy use, the utility has cobbled together dozens of smaller solar-purchase contracts of 10 to 20 megawatts and other small-scale agreements involving geothermal hot spots, wind and other alternative fuels.

The company’s biggest renewable deal thus far involves the co-development of the 200-megawatt China Mountain wind project at the Idaho border.

Until now, the largest solar deal was a power-buying pact with the 64-megawatt Nevada Solar One plant in Boulder City. Nevada Solar One can serve 48,000 homes during peak consumption.

“(Crescent Dunes) is a large, commercial-scale project,” said Tom Fair, vice president of renewable energy for NV Energy. “We have quite a few projects in our portfolio that total far beyond (Crescent Dunes) in the aggregate, but to add a 100-megawatt chunk is significant. ... If it works as it should, I think it’s kind of a breakthrough for these sorts of technologies.”

Crescent Dunes will use mirrors to focus sunlight at the top of a tower. As molten salt flows through the tower, the salt absorbs the reflected sunlight. The plant then stores the salt in tanks until utilities need the sun power for customers. That means solar energy is available even after dark. Typical photovoltaic arrays capture and transmit solar power only when the sun shines.

Kevin Smith, chief executive officer of California-based SolarReserve, said the company chose the Tonopah site not just for its abundant sunshine but also because of its proximity to transmission networks for distribution.

Neither Fair nor Smith would disclose the rate NV Energy will pay for Crescent Dunes’ power, but Fair said the Public Utilities Commission of Nevada will vet prices for their competitiveness. NV Energy will include the SolarReserve project in its Integrated Resource Plan filing, scheduled for Feb. 1. Fair added that the deal locks in rates, so SolarReserve cannot change prices later if construction costs are more than expected or if the project runs into unexpected expenses.

The Washington Post reported in June that officials with the Air Force, which operates the 2.9 million-acre Nellis test-flight range near Crescent Dunes, said they would urge the Bureau of Land Management to reject the plan because its “sensitive” location 25 miles from the range’s border.

The Post said that SolarReserve spent more than 18 months negotiating with the Air Force to revise plans.

Smith said Monday that the Air Force has signed off on the project and sent a letter to the BLM approving Crescent Dunes’ location.

Smith said BLM approval has been fast-tracked, with construction of Crescent Dunes set to start by the end of 2010.

Construction should take about two years, and would create 450 construction jobs and up to 4,000 jobs for local suppliers. Crescent Dunes would generate sales and property tax revenue of more than $40 million over the 25-year deal’s period, SolarReserve officials said. It would employ a permanent staff of 45.

Electricity from Crescent Dunes would go into the power grid that serves Northern Nevada. But after NV Energy finishes its 235-mile One Nevada transmission network, possibly by mid-2012, then north and south grids will connect, and energy from Crescent Dunes will power homes in the Las Vegas Valley.

The technology proposed at Crescent Dunes comes from technology that aerospace company Rocketdyne developed in the 1990s. The U.S. Department of Energy conducted a three-year operating test with a 10-megawatt experimental plant using salt storage near Barstow, Calif., in the late 1990s, but the technology wasn’t yet commercially viable.

In 2008, NV Energy issued a request for alternative-energy proposals that would help it meet state-mandated renewable-energy standards, which call for the utility to get 25 percent of its power from green sources by 2025.

About the same time NV Energy submitted the request, Rocketdyne parent United Technologies Corp. helped get SolarReserve off the ground to use the molten-salt technology. SolarReserve submitted a proposal that, thanks to the storage aspect, stood out from the dozens of bids NV Energy received.

SolarReserve has raised $140 million in venture capital from several private-equity firms. The company did not disclose how much Crescent Dunes will cost to build.

SolarReserve is scouting other Nevada sites for molten-salt plants, and executives are eyeing locations in California, New Mexico, Arizona and Colorado.

Contact reporter Jennifer Robison at jrobison@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4512.

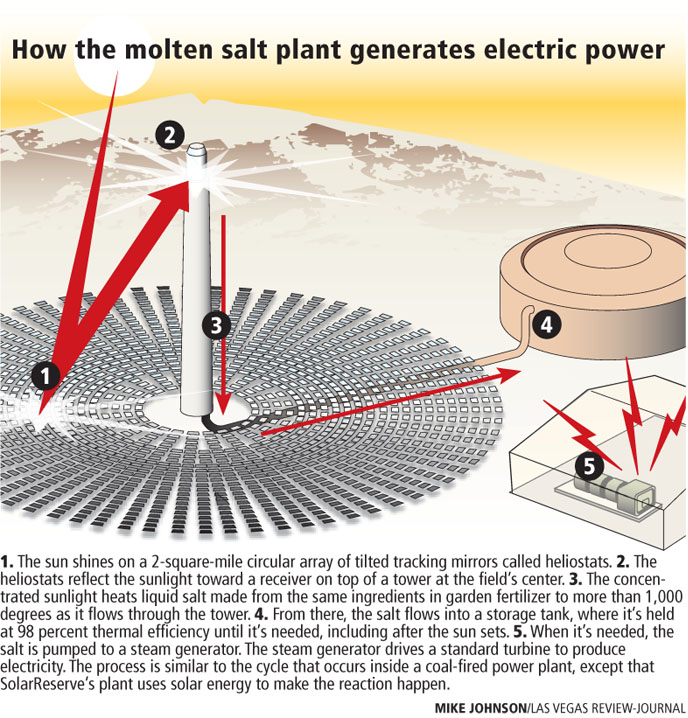

How it works

The sun shines on a two-square-mile circular array of tilted tracking mirrors called heliostats. The heliostats then reflect the light toward a receiver at the top of a tower at the field’s center. The concentrated sunlight heats liquid salt made from the same ingredients in garden fertilizer to more than 1,000 degrees. From there, the salt flows into a storage tank, where it’s held at 98 percent thermal efficiency until it’s needed, including after the sun sets. When it’s needed, the salt is pumped to a steam generator. The steam generator drives a standard turbine to produce electricity. The process is similar to the cycle that occurs inside a coal-fired power plant, except that SolarReserve’s plant uses solar energy to make the reaction happen.