50 years after MLK assassination, housing equality fight continues

Catherine Nelson and her husband, Todd, spent two years on research before deciding on their first Las Vegas Valley home around 2015.

Now ready for more space, they have the same methodical mindset in the search for their next home, but with the added challenges of less inventory, higher interest rates and higher property values.

“You can’t kick yourself,” Nelson said. “There’s so much opportunity out there, and you don’t want to make a mistake.”

The story of upward mobility for the Nelsons — Catherine is a Las Vegas native of black and Chinese descent, and her husband is a Choctaw Native American from Indiana — reflects progress made not only in Las Vegas, but the nation, when it comes to shortening the home ownership gap for people of color.

But the fight for equality continues. Even 50 years after Washington, D.C., added legal protections against discrimination with the Fair Housing Act, a law enacted in the days after the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., disparity still exists locally and beyond.

Denied loans

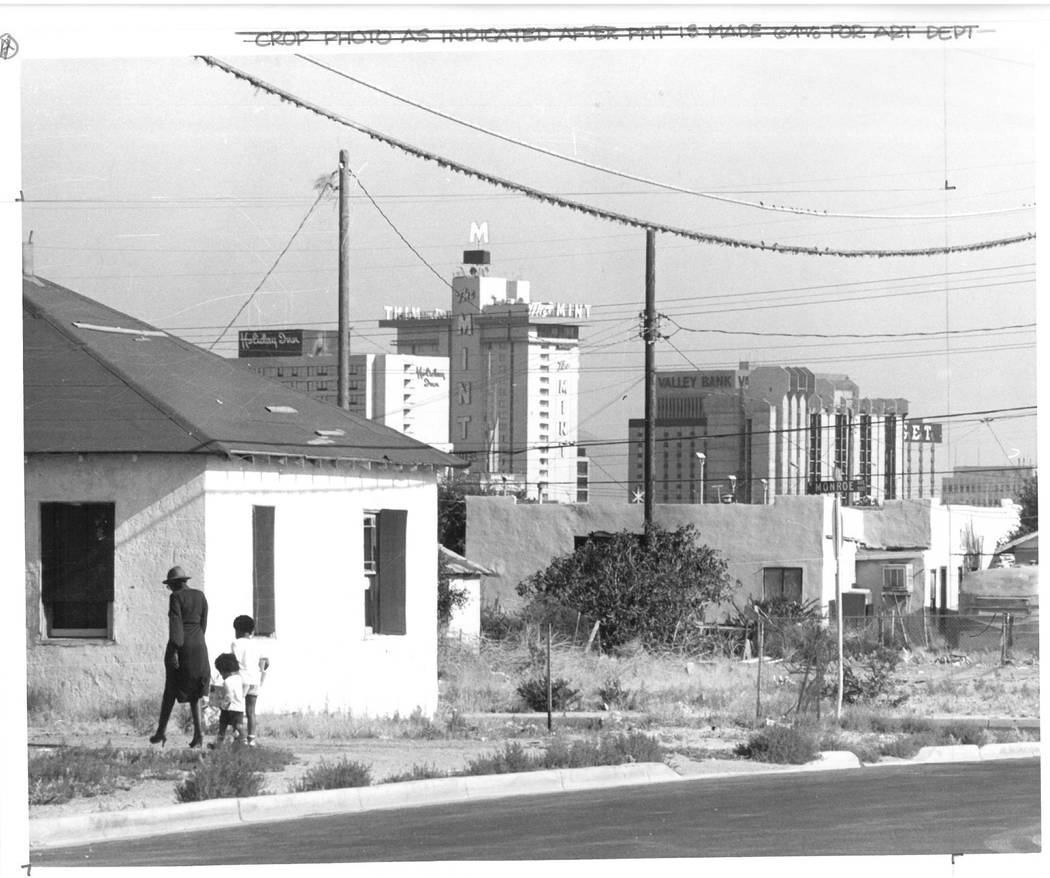

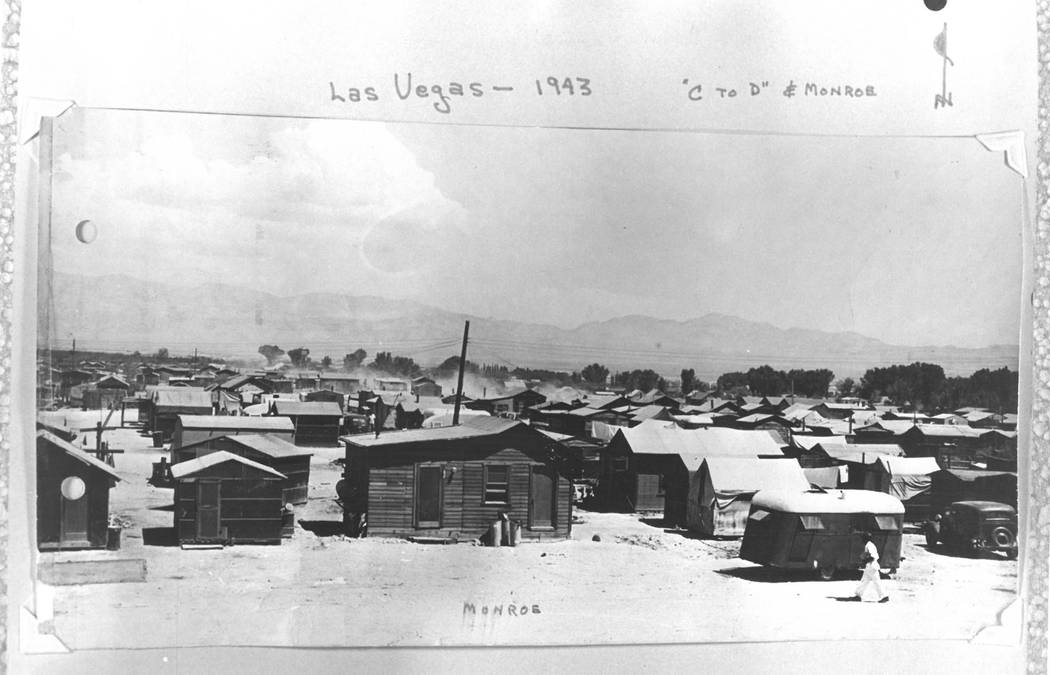

“Shacks” is how Cora Williams described her first homes after she moved to Las Vegas from Louisiana in the early 1950s.

It’s the word she used to describe houses on Monroe and Freeman avenues in a 1975 interview with UNLV as part of the university’s project documenting the black experience in Southern Nevada. The interview came fewer than 10 years after the death of King and birth of the Fair Housing Act.

Williams also described the houses as shacks to her youngest son, Howard Williams, now 53. Cora Williams died in September 2004 at age 73.

In the 1950s, parts of town were off-limits to black Las Vegans, Cora Williams told a UNLV interviewer. Inability to get a loan made building and improving property difficult for black locals.

“You couldn’t get a loan on any house in west Las Vegas,” Williams said. “All black people lived in west Las Vegas.”

No loans also made starting a business difficult. Cora Williams started out as a maid in the hotel industry when she moved to Las Vegas. After six months, she became a beautician and opened Sparks Studio Beauty Shop in west Las Vegas. She served on the state’s Cosmetology Board.

Without loans, people saved money from constructions jobs. They learned to rely on each other.

“They would rotate with each other,” Williams said. “You work on my place this Saturday; I’ll work on yours next Saturday.”

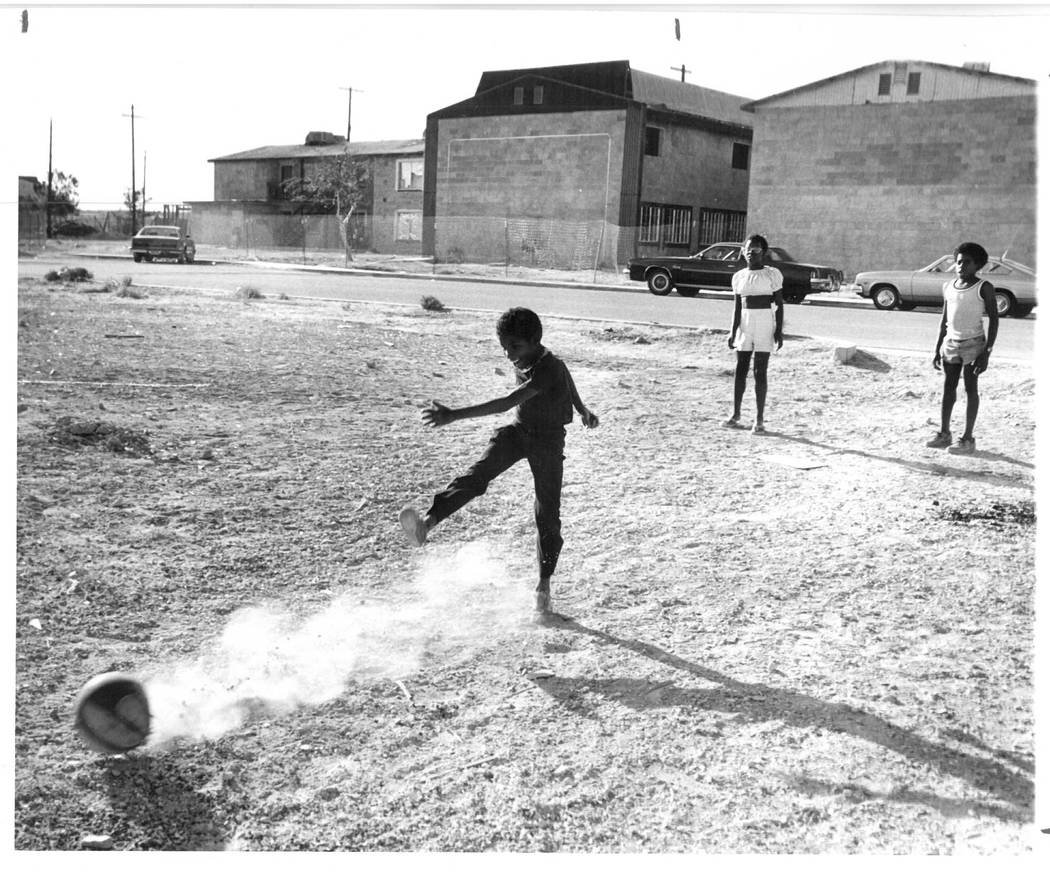

Cora Williams moved into a house on Van Buren Avenue around 1957. Today, son Howard Williams occupies the 912-square-foot house. He moved back in to take care of his mother when she first became sick around 2001.

The neighborhood has changed since he was a kid, Howard Williams said, adding that more police in the area has eased the crime rate. But with all the changes, his boyhood home that Cora Williams built has always been there for himself and his eight children and stepchildren, now in their 20s and 30s.

Data show disparity

Decades after Cora Williams faced strife in Las Vegas, King spoke against discrimination and Congress made housing equality the law of the land, accusations of disparity persist.

In December 2016, the National Fair Housing Alliance sued government-controlled mortgage company Fannie Mae.

The alliance, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit, accused Fannie Mae of taking better care of homes in predominantly white neighborhoods than those in predominantly black and Hispanic communities.

The discriminaion occurred in 38 metro areas, including Las Vegas, according to the NFHA.

In Las Vegas, according to the complaint, 40.6 percent of Fannie-owned homes in communities of color had peeling or chipped paint, compared with 16.7 percent in mostly white neighborhoods.

Some 34.4 percent of its foreclosed homes in nonwhite neighborhoods had overgrown or dead shrubbery, compared with 16.7 percent in predominantly white areas. About 9 percent of its homes in communities of color had a damaged fence, compared to none in mostly white neighborhoods.

Fannie Mae has denied the accusation, saying that it strongly disagrees with the allegations and that its maintenance standards for foreclosed homes “are designed to ensure that all properties are tended to and treated equally.”

Ongoing challenge

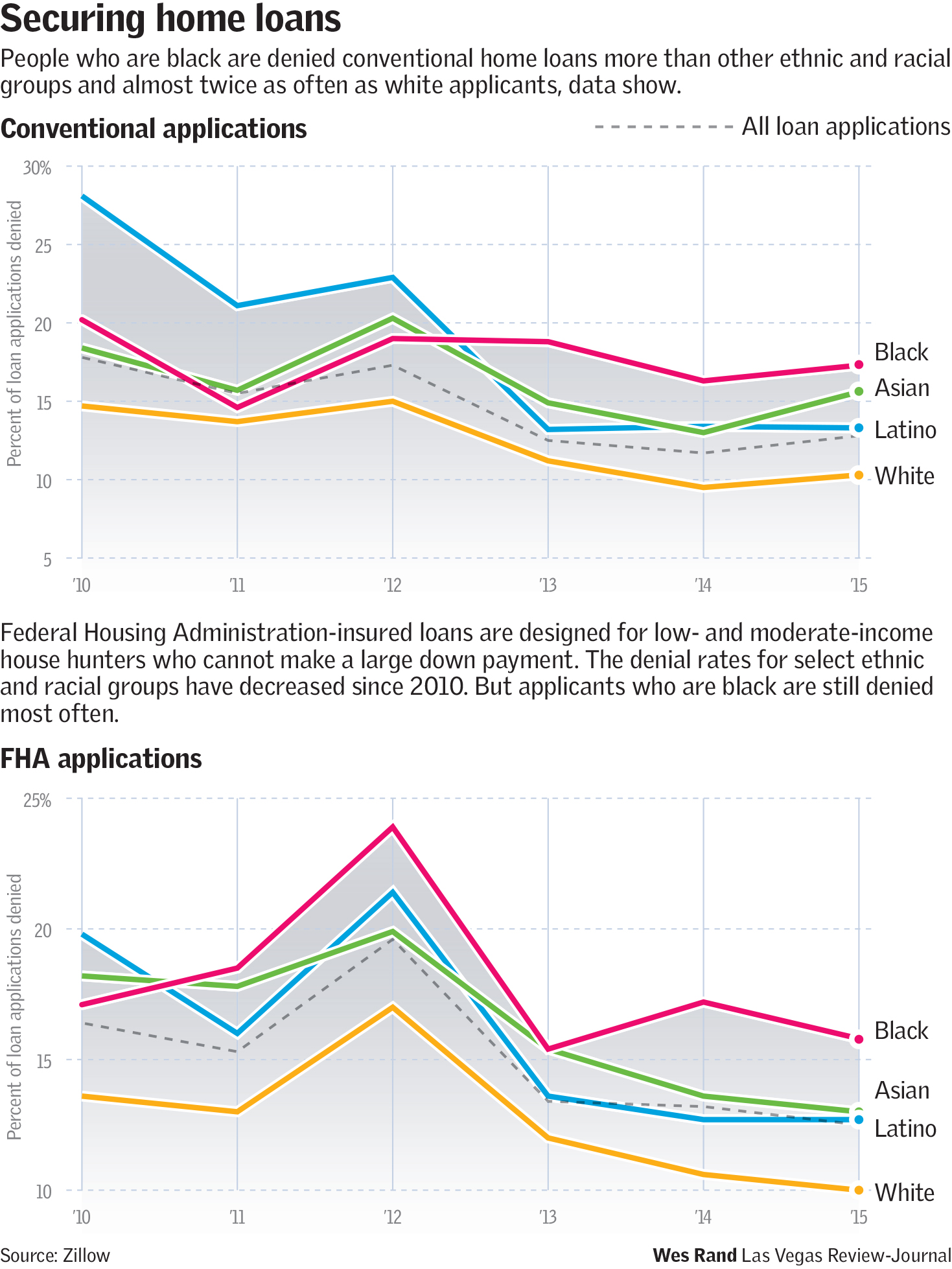

For people like the Nelsons, the Las Vegas couple looking for alarger home, the odds are worse for receiving conventional home loans compared to white applicants.

In November 2016, real estate data company Zillow reported that white applicants in the Las Vegas area were denied loans 10.3 percent of the time in 2015.

Black applicants faced a 17.3 percent denial rate. Asians were denied 15.6 percent of the time. Hispanics were denied 13.3 percent of the time. Denial rates for all groups have shrank since 2010.

Zillow expects to release updated numbers in April, a spokeswoman said.

The Las Vegas area has long had among the lowest rates of home ownership regardless of race. About 50 percent of people in the Las Vegas area owned a home in 1994. The number rose to 63 percent in 2004 and 2006. The rate stood at 51 percent in 2016.

Las Vegas demographics favor the rental market because of borrowing and lending constraints after the financial crisis, said Vivek Sah, director of UNLV’s LIED Institute for Real Estate Studies.

Many Las Vegans already struggle for a down payment large enough to qualify for conventional loans, he said.

Growing home prices only raise the down-payment requirements, pricing people out.

“That is why you may be seeing an apartment boom in the valley,” Sah said. “The Vegas market is dominated by low-end, less-educated jobs in the gaming and hotel industry. These jobs do not make a strong case on qualification for home buying, as the salaries are not stable and a lot are gratuity-based.”

‘Educate the buyer’

Las Vegas real estate agent Tracie Lockett-Green learned the value of home ownership around 8 years old. After her parents paid for their New York house in full, her father burned their mortgage documents to celebrate.

Lockett-Green moved to Southern Nevada about 25 years ago. She saw the Great Recession hit downtown Las Vegas especially hard. She worked with the Neighborhood Stabilization Program to help rehabilitate foreclosed houses, helping 90 homeowners. The program helped around 3,000 Nevadans.

The program lost funding in 2014.

The way to improve home ownership among people of color and people with low incomes is education, Lockett-Green said.

Not enough people know what agencies to go to for assistance, what determines a credit score, or how to improve inherited property to increase its value, she said.

Disadvantaged groups are making up for generations of lost time building wealth and credit. For Lockett-Green, government programs, employer programs, online resources, and programs from organizations such as the Culinary union help first-time homeowners close the gap.

“This should be in high schools,” she said. “We’ve got to educate the buyer.”

Contact Wade Tyler Millward at wmillward@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4602. Follow @wademillward on Twitter.