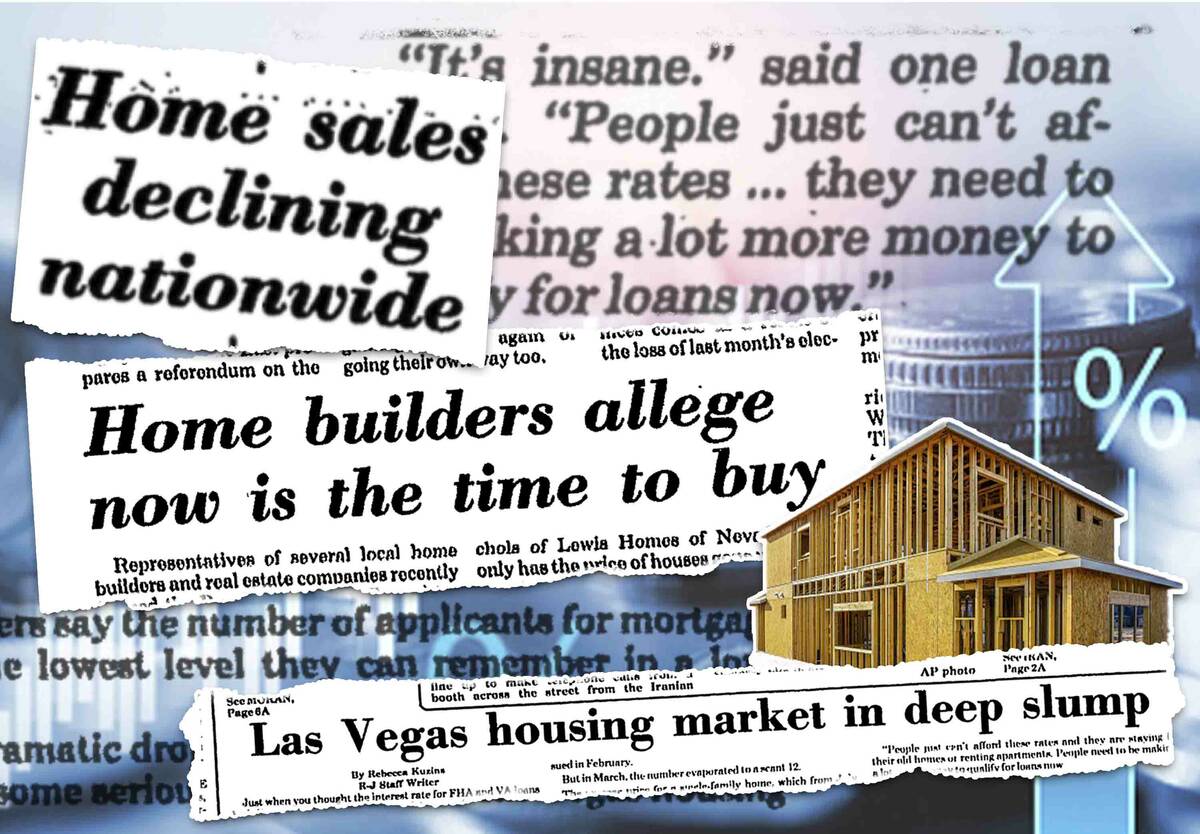

Las Vegas housing market recalls ‘insanity’ of the early ’80s

With homebuyers facing sky-high mortgage rates, news reports were bleak.

Las Vegas’ housing market was in a “deep slump,” home sales were “declining nationwide,” and U.S. home construction was in a “furious downturn.”

“It’s insanity. … People just can’t afford these rates,” a lender told the Review-Journal.

Southern Nevada’s housing market pumped the brakes in 2022 amid fast-rising mortgage rates. But it wasn’t the first time increased borrowing costs slowed home sales.

Those dire reports were from the early 1980s, when mortgage rates were vastly higher than they are now.

The average rate on a 30-year home loan was 6.31 percent as of mid-December, up more than double from a year earlier. But it was nowhere close to the rates people paid in October 1981, when the average peaked at 18.63 percent, federal data shows.

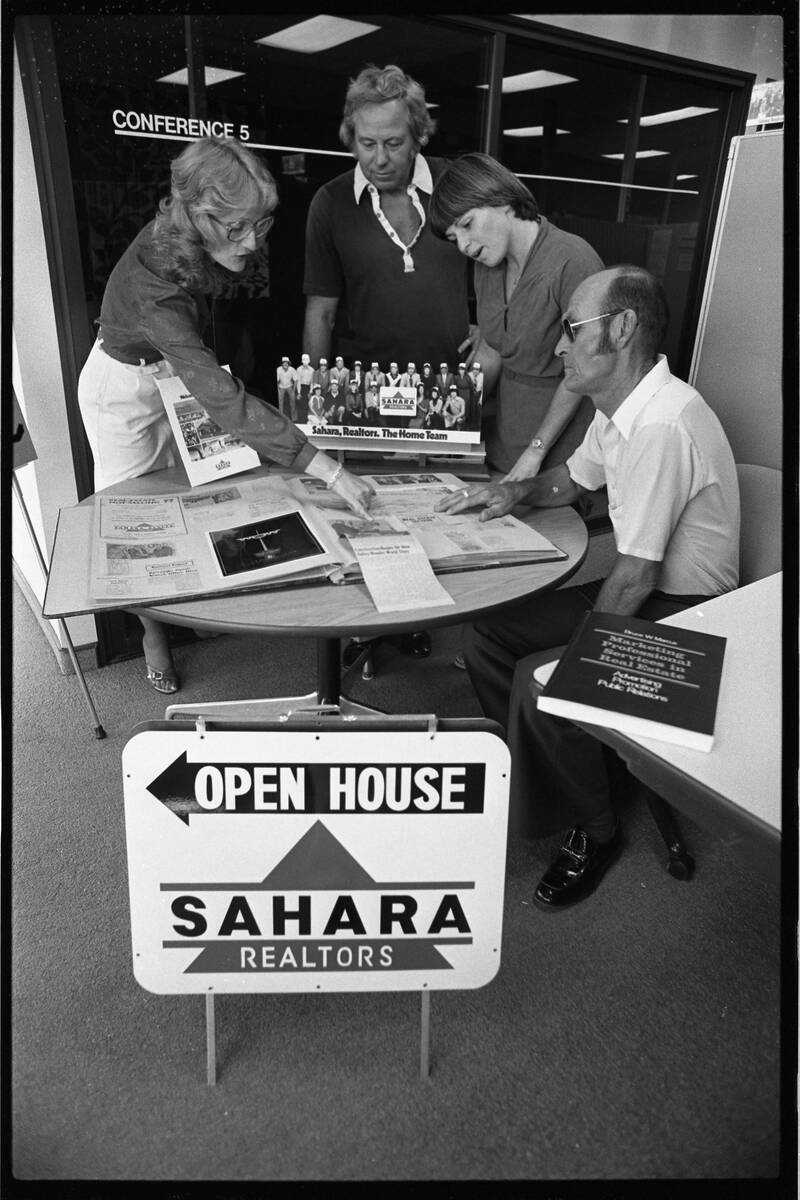

Las Vegas builders tried hard to keep people buying back then. A new development touted the benefits of people teaming up to purchase a house. There was even a Buy Now Housing Committee consisting of local builders that sought to “present a balanced and accurate account of the housing market in the Las Vegas area.”

“A home will never cost less,” the group declared in April 1980, when mortgage rates topped 16 percent.

‘Hard-pressed real estate industry’

Jack Woodcock, who has been working in Las Vegas’ real estate market since the 1970s, said it was “very difficult to get a loan” in the early 1980s if a buyer’s income didn’t support it.

There were also layoffs in the industry, as high mortgage rates had slowed activity, recalled Woodcock, a broker with Berkshire Hathaway HomeServices Nevada Properties.

Woodcock said Las Vegas’ housing slump didn’t last long. The local population kept growing, and some buyers figured they would refinance when rates fell, he recalled.

House hunters also had a way around the elevated rates.

Buyers could assume a seller’s mortgage as part of a home purchase, a practice that let house hunters lock in lower rates than they’d get with a new loan, Woodcock said.

“There’s no way they could have gotten that kind of rate, no question,” he said.

When the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a regulation allowing restrictions on these so-called assumable mortgages in 1982, The Washington Post said it was “a defeat for the hard-pressed real estate industry.”

Real estate interests “vigorously opposed” the justices’ action “on the grounds that assumable mortgages have enabled millions of home buyers to purchase at lower interest rates,” The Post reported in June 1982.

Lenders said the practice was “draining them of millions of dollars in new and more lucrative loans at a time when they need money most,” the paper reported.

‘House-sharing’

In an attempt to fight rising inflation, the Federal Reserve took aggressive steps that ended up pushing the country into a double-dip recession in the early 1980s.

Mortgage rates, which largely hovered in the 7 to 10 percent range in the 1970s, shot higher, approaching 19 percent by fall 1981, federal data shows.

“It used to be that the husband and wife both would work so they could qualify for a mortgage loan,” a lender told the Review-Journal in 1980. “But now even if they both work, they still can’t qualify. For young married couples, it’s just a mess.”

By the spring of 1980, local builders had formed the Buy Now Housing Committee to “combat negative publicity” surrounding high interest rates and its effect on the industry, according to an article in the Review-Journal.

“The only answer to the home buyers’ dilemma of increasing interest rates and increasing home costs is to buy now,” a builder said.

Amid these efforts to boost sales, the U.S. homebuilding sector was in rough shape: As seen in government statistics, home construction was “on a furious downturn,” The Associated Press reported in spring 1980.

“I’ve never seen it like it is now,” a Midwestern builder said in the article. “I think this year is going to be a complete loss.”

In spring 1981, a story in the Review-Journal reported that high interest rates and home prices had spurred the growth of “house-sharing,” in which two buyers “pool their financial resources and purchase a home together.”

Spanish Villas, a new townhouse community at Desert Inn Road and Decatur Boulevard, was “introducing” the concept to Las Vegas, with homes boasting two master bedrooms, “usually at opposite ends of the house,” the story said.

“This type of home is perfect for prospective homeowners who want to buy a nice home in a nice neighborhood without paying high mortgage payments,” said a marketing director for Spanish Villas.

Nationwide, sales of previously owned homes plunged by 50 percent between 1978 and 1981, and builders’ sales and permits “fell by similar amounts,” according to a 2009 article by American Enterprise Institute senior fellow emeritus Mark Perry.

“Simply put, the housing market crashed under the weight” of high mortgage rates, Perry wrote.

‘Much more devastating’

Echoing that period, high inflation prompted the Federal Reserve to boost interest rates several times in 2022. Mortgage rates soared, wiping out the cheap money that fueled America’s unexpected housing boom after the pandemic.

Housing markets slowed across the country. In Southern Nevada, sales totals plunged from 2021 levels, sellers increasingly slashed their prices, available inventory skyrocketed and builders offered more incentives to prospective buyers.

On the resale side, 1,521 houses traded hands in November, down 53.5 percent from the same month last year, while 7,342 houses were on the market without offers at the end of November, up 161.7 percent from a year earlier, trade association Las Vegas Realtors reported.

On the construction side, builders logged 350 net home sales — newly signed purchase contracts minus cancellations — in Southern Nevada in October, down 59 percent from the same month last year, Las Vegas-based Home Builders Research reported.

Builders also pulled 545 new-home permits in October, down 55 percent year-over-year, indicating a sharp drop in construction plans, and their land buying was “basically non-existent,” wrote Andrew Smith, the research firm’s president.

Buyers today spend more of their paychecks on housing than they did some 40 years ago, said Woodcock, who noted that incomes haven’t kept up with home prices.

Woodcock, for one, figures the increased mortgage rates of the past year have been “much more devastating” to would-be buyers than they were in the early 1980s.

“It didn’t have the same effect,” he said.

Contact Eli Segall at esegall@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0342. Follow @eli_segall on Twitter.