Mediation process leaves both homeowners, lenders unhappy

The Nevada Supreme Court, which oversees the Foreclosure Mediation Program, has several times in the past 18 months updated program rules in response to concerns that have arisen, but bank officials and homeowners say the program still has problems that must be addressed.

At a meeting with homeowners' representatives this month, homeowners complained about the process as much as the lenders, said Barbara Buckley, former speaker of the Assembly and author of the 2009 legislation that created the mediation program.

Homeowners said the program should track how often lenders do not negotiate in good faith, and should establish a sliding scale for financial sanctions based on the lenders' track records.

In addition, Buckley said attorneys for homeowners in three different areas of the state told her of cases in which a bank charged a homeowner for the bank's half of the $400 mediation fee that the law states is to be split evenly.

For other homeowners, problems have surfaced as they navigate the mediation process with mixed results.

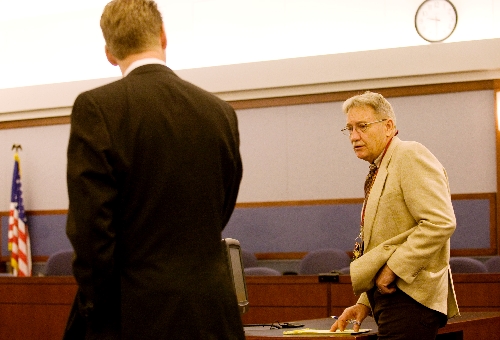

Longtime Las Vegas attorney David Crosby, who said he has dozens of clients facing foreclosure, is expected to present arguments to the state Supreme Court Feb. 7 on behalf of homeowner Moises Leyva, said Troy Fox, an attorney with Crosby's firm. He said Leyva's lender didn't bring the required records to the mediation, but District Court Judge Donald Mosley authorized a foreclosure after he ruled the lender provided sufficient documentation.

Leyva is asking the court to clarify the definition of good-faith negotiating at a mediation, and to determine how much weight the Supreme Court give District Court deliberations on appeal, Fox said.

In addition, Crosby is handling a second appeal filed with the state Supreme Court in late November. Besides seeking a reversal of that decision, the appeal asks the court to clarify multiple aspects of the law, from terminology, to the role of its administrators, to sanctions it can impose on those who won't play fairly.

"First, we want the bank to come to the table and work with them (clients) to save their home. It's absurd for the bank to sell the home for very little when they could work with the customer and avoid the foreclosure," Crosby said. "Second, the system needs to be adjusted a bit. There need to be standards for when the program administrator issues a certificate of foreclosure or not. She should know when she can and when she can't without having to make legal decisions. Leave that for a judge."

Bill Uffelman, president and chief executive of the Nevada Bankers Association, said the foremost concern for banks isn't the foreclosed homeowners who pursue mediation, but the larger percentage of homeowners who express no interest in it.

Even when a homeowner doesn't request mediation, the Foreclosure Mediation Program takes up time examining the case before authorizing a foreclosure, Uffelman said.

"My expectation was that if the borrower did not respond (in requesting mediation) within 30 days, you could move forward with the foreclosure. ... That is the step that is not clicking," Uffelman said. "If there is no mediation requested, why do we need to send in all the paperwork (to the administrator)? You are sending in mountains of paperwork when you should only have to send in paperwork in about 10 percent of the cases."

Buckley acknowledged that banks should be allowed to foreclose if they can show a homeowner has no interest in mediation, but she also recalls a high-profile case in which a bank foreclosed on a home only to learn that the owner was serving in Iraq when the foreclosure notice was mailed.

"You have to have a balance," Buckley said. "We don't want to delay the process when a homeowner doesn't want to participate; but, on the other hand, we don't want to deprive a homeowner of a chance to participate when a lender hasn't notified him."

If the mediator determines either side failed in its requirements, or did not negotiate in good faith, the other party can appeal the matter to a District Court judge. The judge is expected to determine whether further negotiations are warranted, whether a foreclosure should move forward or whether a second mediation is needed.

Crosby's Supreme Court case appeals a decision, by Clark County District Judge Donald Mosley, to allow foreclosure against the home of Evangelina Quintana-Turek. The appeal asks the court to define what constitutes good-faith negotiating by a lender, a "lack of authority" to negotiate on the bank's behalf, the mediator's role and authority, and a judge's obligations when considering an appeal from a mediator's decision.

The Quintana-Turek case asserts that the chief administrator of the Foreclosure Mediation Program, Verise Campbell, exceeded her authority by allowing the lender to foreclose even though the lender didn't negotiate in good faith. Campbell doesn't have authority under the law to make such life-changing decisions, Crosby said.

"Verise Campbell issued a certificate of foreclosure contrary to the legal opinion of her attorney," Crosby said. "And, as soon as we got into (Mosley's) court on it, she rescinded the foreclosure, so there seems to be something wrong with the process."

However, since Mosley approved the foreclosure anyway, Quintana-Turek moved forward with the appeal.

Campbell, a deputy director of the state's Administrative Office of the Courts, who oversees the Foreclosure Mediation Program, couldn't be reached for comment. Michael Sommermeyer, spokesman for the Foreclosure Mediation Program, said program administrators are prohibited from commenting on litigation before the state Supreme Court because the court oversees the program.

"It's a new law and it needs a few adjustments," Crosby said.

Many concerns in the Quintana-Turek appeal are also raised in a court challenge filed last month in Washoe County District Court on behalf of a Northern Nevada couple, said the couple's attorney, Phil Olsen of Incline Village. He was a mediator with the program for a few months, but was let go last year.

The petition for a writ of mandate was filed last month. Among other issues, it asks the court to confirm lenders' obligations under state law and explain how a homeowner appealing a decision is supposed to recount the mediation session, since recording the negotiation is forbidden. Homeowners and banks are allowed to take notes during the mediation, and are allowed to keep those notes after the negotiation, Sommermeyer said.

Another big problem, Olsen said, is that program administrators are bridling mediators in violation of the state law. Administrators have told mediators they are not authorized to recommend sanctions against lenders, yet the law says that is part of their role, Olsen said.

Neither bank officials nor their attorneys are required to cooperate with news media. As a result, nearly a dozen attorneys litigating foreclosures in District Court on behalf of Bank of America, Wells Fargo and other large lenders would not comment for this story.

Instead, Uffelman, from the Bankers Association, confirmed that large lenders will not speak publicly about their policies on foreclosures or the effectiveness of the state's mediation program.

Uffelman said "stakeholders" met earlier this month with Buckley, D-Las Vegas, and newly elected Assemblyman Jason Frierson, D-Las Vegas, to discuss problems with an eye toward addressing them in the upcoming session of the Legislature.

One frustrated mortgage lender recently told Uffelman she has hundreds of homes ready to foreclose on, but that she could take control of only a handful because the mediation program was holding her up.

"There is a problem with the conclusion to the nonmediation cases," Uffelman said. "There is a delay when we try to get the (foreclosure ) certifications for the nonmediation cases."

Sommermeyer said the mediation program has a backlog of about 2,000 foreclosures to examine before either scheduling a mediation or issuing to the lender a certificate to move ahead with a foreclosure.

He acknowledged that the law gives a homeowner 30 days to apply for mediation after receiving the first foreclosure notice, but he said the program staff takes additional time after the deadline to double-check whether the homeowner truly isn't interested in mediation. It's possible the homeowner didn't open the mail or that the application got lost in the mail, he said.

"If they don't opt into the program, we want to make sure that they have that opportunity," Sommermeyer said. "We think it is appropriate because it gives us time to do that research. ... We are not in the homeowners' corner, but our mandate is to provide homeowners and lenders an alternative to foreclosure."

Another concern of bank officials is the program's failure to disqualify on the front end of the mediation process cases that are ineligible for the program. Too often banks are required to prepare for mediation only to learn later that the home is not owner-occupied, and is thus ineligible, Uffelman said.

Sommermeyer said mediation program staffers weed out clearly ineligible property owners when applications are received. However, the staff must assume a homeowner is being truthful on the application, or the verification process would take far too long and further delay mediations, Sommermeyer said.

If homeowners lie on applications, the truth typically comes to light and could lead the mediator to determine the homeowner didn't negotiate in good faith.

A third problem mentioned by bank officials involves mediations that conclude with a temporary agreement to sell the home for less than the amount owed on it. In such a "short sale," the lender typically eats the difference between the sale price and the amount remaining on the debt. The bank typically gives a homeowner two or three months to accomplish a short sale. But very often, the homeowner fails to sell within the allotted time, and the bank must start the foreclosure process all over again.

Sommermeyer said the mediation program is aware of the problem, but the rules prohibit the program from authorizing a foreclosure if a temporary agreement is in place.

One way around the predicament may be to set a deadline for any temporary agreement, and allow a foreclosure to proceed if the terms of the agreement are not met by the deadline, Sommermeyer said.

Contact reporter Frank Geary at fgeary@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0277.