Nevada’s labor force still struggling during pandemic

Retailers at Las Vegas North Premium Outlets enticed job seekers on Thursday morning with a variety of tactics, from sugar cookies coated with orange icing, treats from Starbucks to a goody bag featuring a QR-code leading to an online job application.

The outdoor mall near downtown Las Vegas hosted its first holiday job fair of the year to help the 31 participating retailers fill about 100 seasonal positions. But halfway through the three-hour event only a handful of job seekers had arrived.

“The turnout has been very light, but we’re hoping it picks up later because Las Vegas is a later-type town,” said Vicki Rousseau, area director of marketing and business development for the North and South Premium Outlets. “It’s been challenging for (retailers) to find employees, so that’s why we figured if we got everybody together, we would hopefully help them see a pickup in employment.”

Rousseau later shared that the job fair brought in a couple dozen people, though she’s unsure if any offers were made.

Low turnout at job fairs is no anomaly. Businesses across Nevada expected a flood of job applications after the enhanced federal unemployment benefits ended Sept. 4. Instead, they’re still struggling to fill open positions.

Meanwhile, Nevada’s unemployment rate has consistently declined since the height of the pandemic in April 2020, when the state reported an unemployment rate of 29.5 percent.

A declining unemployment rate is generally a harbinger of good news — signaling a recovery — but experts say other metrics from labor force participation to other measures of unemployment show a number of reasons why thousands of Nevadans are not fully back in the workforce.

“What you might see is people who aren’t looking for work because they expect to be recalled by their former employer or they’re not working because they are looking for child care,” said David Schmidt, chief economist for the Department of Employment, Training and Rehabilitation. “So any of those factors of ‘I didn’t look for work in the last four weeks’ would push someone out of unemployment and out of the labor force, which is why you see that big decline in the unemployment rate.”

Another measure of labor

The unemployment rate widely reported nationally including by DETR, known as the U3 unemployment rate, counts people who don’t have a job, are available for work and have actively been looking for work in the prior four weeks.

But the U3 rate doesn’t always show “the overall strength of the market” and “underestimates labor market distress increases during a recession,” according to an April report by Boston College professor Christopher Baum and Tufts University professor Michael Klein.

The pair pointed to another metric, called the U6 unemployment rate, as one showing a fuller picture since it includes people not counted by the official unemployment rate.

The U6 rate not only includes the unemployed counted under the U3 rate but also adds workers who have been forced to work part time for economic reasons and those who stopped looking for work in the past month but did in the past 12 months.

Baum and Klein argue that a failure to account for the U6 rate means policy decisions may not match up to what is really needed to help the labor market recover.

For Nevada, the latest reported U6 rate is 17.9 percent for the second quarter of 2021, which the Bureau of Labor Statistics measures as a 12-month average, or from July 2020 to June 2021. For the first quarter of this year, it was 21.8 percent while the fourth quarter of 2020 it sat at 19.6 percent.

And while the latest U6 rate has improved from the previous quarter, it remains significantly higher than the state’s monthly unemployment rate, currently at 7.5 percent, indicating many workers are still struggling to get back on their feet.

Declining labor force participation

Peter Norlander, an associate professor at Loyola University Chicago, said labor market conditions also haven’t changed much compared to last year.

“Even though we’re not in the depths of the crisis that we were in, the overall picture is still really bad from a labor force participation perspective,” said Norlander. “That is the percentage of the working age population that is in the labor force, and you still have millions of people across the country who have dropped out and that includes older workers, women, minority workers.”

Nevada reached its highest labor participation rate in 1982 when the monthly rate stayed close to 74 percent. It continued to slide down over the years, reaching 61.6 percent last month.

Since the BLS began tracking the rate in 1948, the labor force participation in the U.S. peaked during 1999 when it hovered just over a seasonally adjusted 67 percent — even higher for those aged 25 to 54 with a rate of about 85 percent.

But ever since the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, the rate has steadily declined to 61.6 percent for September.

“It’s a long-term story of weak labor markets in the United States and inadequate recovery,” Norlander said. “We’ve been hit with the dot-com (bubble), the Great Recession, COVID — crisis after crisis, and no recovery has brought us back to where we were in 1999.”

But it’s expected to drop lower, reaching 60.4 percent in 2030, according to a BLS report this month, which cited the decline to slower population growth and baby boomers reaching traditional retirement age.

Hitting the pavement

Precious Briggs, a former cocktail server at Palace Station, was laid off in March last year like thousands of other casino workers.

“I’ve been hoping to get my job back, but I haven’t been working anywhere else,” Briggs said. “I never imagined being shut down completely like this then not having your full-time job call you back. Never imagined it.”

She’s only found a few full-time job openings and said the job search has become frustrating, adding that the passage of Senate Bill 386, dubbed the “Right to Return” bill, should’ve brought her back to Palace Station. She’s been able to survive on savings and help from family but needs to find a job this year.

“Before the pandemic, Vegas was up and rolling. It was nothing to get a job,” she said. “It’s very different now. There aren’t any full-time positions — well, there are some — but not many full-time positions to accept.”

Las Vegan Chelsea Ortiz, who lost her call center job in April 2020, said it took nearly a year to find a new job. She said many employers either never responded after she applied or called to say they were “not hiring because of COVID.”

“I did get discouraged for about a month,” she said. “My mental state just kind of declined because I thought, ‘Oh, I’m never going to get this.’ It’s been a really hard journey.”

But even the new position Ortiz snagged as a retail associate wasn’t enough, as she was working only two days a week.

She continued scouring Indeed and joined job groups on Facebook, where she learned about Goodwill of Southern Nevada’s partnership with NV Hope. The program offers free career training helping participants train for and pass the Certified Nursing Assistant licensing exam.

“I just passed my exam in September, and I already got a job offer at Centennial Hills Hospital so I’m so excited,” said Ortiz, whose goal is to become a registered nurse.

Schmidt said there are thousands of Nevadans like Ortiz, who are considered underemployed because they can’t yet find full-time work or their hours have been cut back.

He said the latest figure, 90,600 workers, is almost close to what it was just after the Great Recession when there 105,400 workers forced to work less than 35 hours per week.

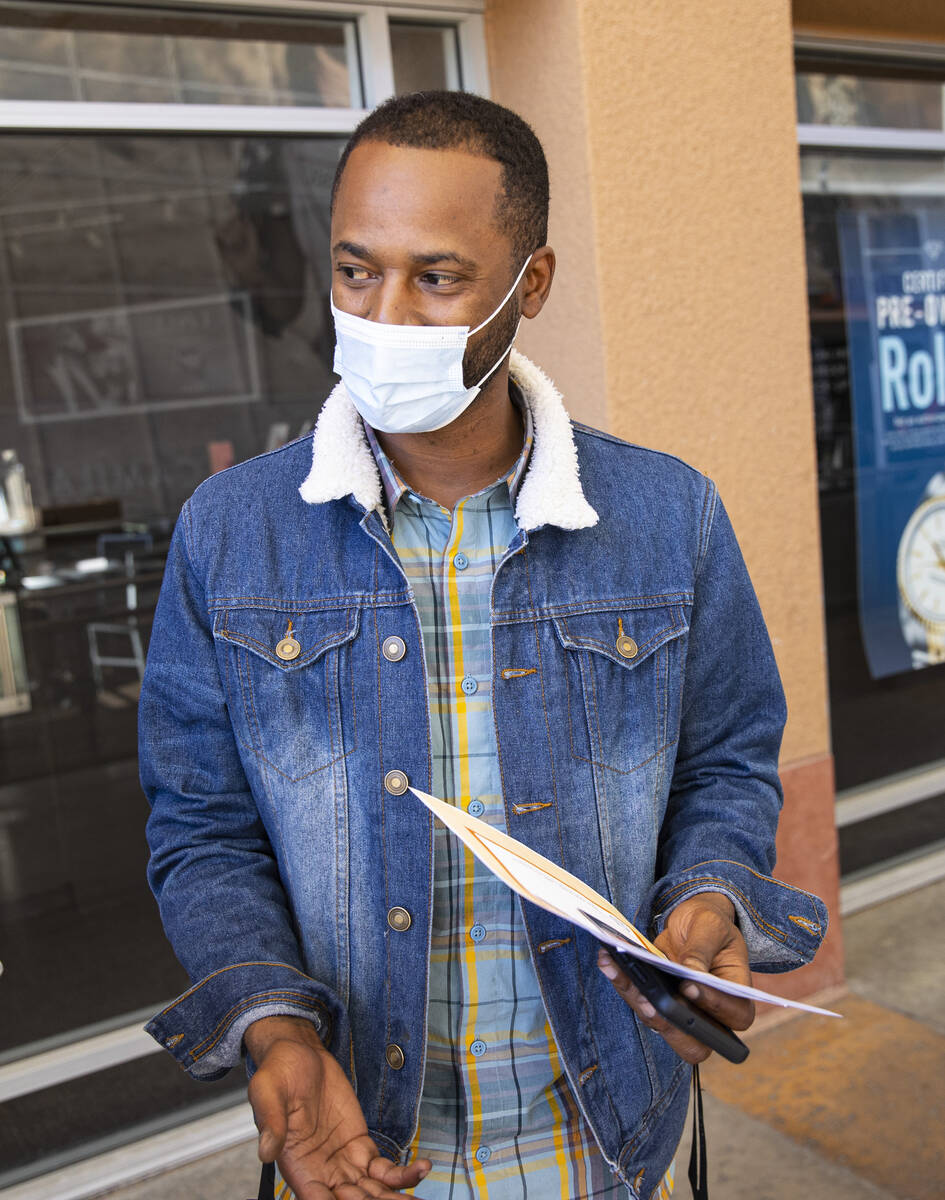

“It has been difficult to be gainfully employed instead of underemployed,” said Las Vegas resident Javane Smith, who was at the Premium Outlets job fair.

Smith, who worked at a luxury boutique inside a Strip hotel shopping center, was laid off last year and has struggled to find a full-time supervisor position paying more than $15.

“I have a bachelor’s degree. I have experience, and I can’t afford to live off that,” she said. “Housing costs went up so much, and the wages aren’t keeping up with it.”

She said she’s able to be slightly picky after hoarding all of her extra unemployment benefits and slashing her expenses. She also moved back home after her lease expired.

“I’ll be OK where I can afford to be more choosy, but not everybody is blessed to be in that situation,” she said. “Some people, especially with kids or other responsibilities, they don’t have that luxury. It’s a tough climate.”

Contact Subrina Hudson at shudson@reviewjournal.com. Follow @SubrinaH on Twitter.