Some Nevada employees see dents in pay because of wage theft

After three years of driving for Omni Limousine, Kevin McSwiggin was fed up with his job.

According to filings with the U.S. District Court for Nevada, Omni employees were only paid an hourly wage if they were driving a client. Time spent cleaning the limo, completing paperwork, filling the vehicle with gas or verifying trip sheets was ignored.

Documents from the federal court allege McSwiggin was underpaid nearly $800 in a two-week period. His wife, Christy McSwiggin, faced similar difficulties at the company.

“We were doing office work but not being paid for it,” Christy McSwiggin told the Las Vegas Review-Journal. “They weren’t paying for the first hour they required us to be there or the last hour.”

An Omni representative declined to comment for this story.

The couple’s 2014 case against Omni ended in a settlement, and the couple have moved to Nashville, Tennessee.

A document filed with the U.S. District Court on May 7 said Omni has paid the two former employees in full.

Wage theft is a recurring problem found in a range of industries across the state, according to a 2018 study. Today’s tight labor market isn’t expected to help.

Nevada’s findings

Nevada Labor Commissioner Shannon Chambers said wage theft cases — instances where a company tries to raise profits by forcing employees to work off the clock or not paying them for overtime work — have been on the rise in Nevada over the past four years. But that doesn’t necessarily mean more companies are engaging in illegal practices.

“We are receiving more claims,” Chambers said. “Part of that is because our economy is improving again, and there are more people in the workforce.”

Back wages on the rise

In fiscal 2018, the U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division collected an average of $835,000 for workers per day in back wages — the difference between what an employee was paid and the amount that employee should have been paid.

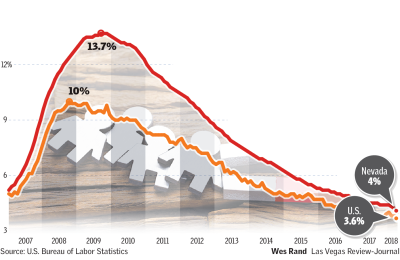

The Department of Employment, Training and Rehabilitation reported that unemployment in Nevada dropped to 4 percent in April, the lowest in 13 years.

Nevada isn’t the only state facing wage theft disputes, according to a 2018 study by national policy resource center Good Jobs First.

The report analyzed 1,200 wage theft litigation cases against large companies that have been resolved since the start of 2000, including 30 cases from Nevada. Harrah’s, Sierra Pacific Power Co., Red Rock Resorts, Walmart and Wells Fargo were some of the companies listed.

“People associate Walmart with some of these issues … but there were other large organizations, including ones we didn’t expect like banks, high-tech companies, pharmaceutical companies,” said Philip Mattera, research director at Good Jobs First.

A spokeswoman from Walmart said the company is committed to paying its 1.5 million associates for every hour worked.

“We take this commitment seriously and have worked hard to have the right processes, technology, and systems in place to make Walmart a rewarding and great place to work,” she said via email.

Recent cases in the report include a $700,000 settlement in 2017 with West Business Solutions, a call center in Reno, and a 2016 case involving Bloomin’ Brands — the parent company of Outback Steakhouse and Bonefish Grill — that ended with a $3 million settlement.

In all, the report found more than $97 million of wage theft-related cases in Nevada among 24 parent companies, 17 of which had multiple cases listed in the report.

“It was surprising for us to see those repeat offenders,” Mattera said. “It’s not like they get sued once and clean up their act. It really raises the question of whether these abuses are a part of their business strategy.”

Caesars Entertainment Corp. — the owner of Harrah’s — and West Business Solutions declined to comment. Bloomin’ Brands, Red Rock Resorts and Sierra Pacific did not respond to requests for comment.

A tight labor market

Nevada’s unemployment rate dropped to 4 percent in April, the lowest in 13 years. This has led to an increase in wage theft cases investigated by the Nevada labor Commission.

A spokesman for Wells Fargo said, “It is not uncommon for large employers to face at any time a wide range of wage and hour class-action litigation, especially in California. Wells Fargo is not an exception to that.”

Impact on employees

Wage theft can take on several forms, like ordering an employee to clean before clocking in or a manager enforcing an off-the-clock “pre-shift” meeting.

“If you’re not being paid for work time, that’s a huge impact to an employee,” local attorney Christian Gabroy said. “On the aggregate, employers make millions every year on wage theft.”

A 2017 report from the Economic Policy Institute found that in the 10 most populous U.S. states, workers suffering minimum wage violations are underpaid $64 per week on average. That’s nearly one-quarter of their weekly earnings.

In all, the report said more than $15 billion in wages are lost annually to minimum wage violations in the U.S.

“You should be paid for every hour you work,” Gabroy said. “You can’t just look at it as only 15 minutes of someone’s time. … These are hard-earned wages from employees. They have to take away time from family. They’re getting work for nothing.”

And that could lead to issues like debt, according to the McSwiggins. They said their lost wages forced them to rack up more than $100,000 in credit card debt.

While lawsuits are meant to get those lost earnings back in workers’ pockets, some say they could lead to unemployment.

Current cases

Las Vegas resident Tijuana Campbell entered a still-pending class-action lawsuit against her former employer, Southwest Gas Corp., last year after she alleged the company was not paying her for overtime work.

Campbell said she and two co-workers were terminated after their names were revealed in the lawsuit.

You should be paid for every hour you work. You can’t just look at it as only 15 minutes of someone’s time. … These are hard-earned wages from employees. They have to take away time from family. They’re getting work for nothing.

Christian Gabroy, local attorney

“We were punished,” she said. “We were scrutinized more severely and harshly than the other 15, 16 dispatchers that worked in the department. … They were trying to find ways for us to resign or terminate us.”

A Southwest Gas representative said the company does not comment on pending litigation.

Campbell signed a settlement on May 2, according to records with the U.S. District Court.

Small and large businesses

Chambers said wage theft isn’t a rampant issue in Nevada, but there are some players who abuse the system.

“There are businesses that are intentionally doing this,” she said. “But I think it’s a small percentage.”

They can be found in businesses of all sizes, she said. But larger corporations often have resources that smaller businesses can’t bring to bear — like attorneys — and can afford to educate their staff on wage theft laws.

“With the larger employers … if it’s brought to their attention, they’re able to fix it very rapidly,” Chambers said. “Newer, smaller businesses, or those from out of state, may not be as informed or up-to-date on Nevada laws,” like its two-tier minimum wage system. Nevada’s minimum wage is $7.25 per hour for employees with health benefits and $8.25 for those without.

For the most part, Chambers said, companies work to fix the issue as soon as it’s brought to their attention. But there are exceptions.

There are “some out there that just won’t comply,” she said. “You’re certainly going to have some companies and businesses that are going to push everything to the edge … and that’s a corporate decision they have to make.”

Finding a solution

Mattera said companies that are caught practicing wage theft often face financial repercussions, but that might not be enough to dissuade them from continuing the practice.

Newer, smaller businesses, or those from out of state, may not be as informed or up-to-date on Nevada laws

Nevada Labor Commissioner Shannon Chambers

In the Good Jobs First report, penalties in Nevada ranged from $5,418 for Reno Newspapers Inc. in 2005 to $85 million for Walmart in 2009 from a consolidated case among several states.

“I don’t think any of these amounts were make-or-break numbers for the company,” he said. “The sums are not astronomical.”

Chambers said the Law Commissioner’s Office is allowed to fine employers up to $5,000 for each violation.

The office’s first goal with wage theft cases is to get the money back to the worker, Chambers said, which means forcing a company to the edge of bankruptcy could hurt the employee too.

The office instead tries to keep businesses up-to-date on regulations through training seminars and educational outreach.

“I think education is our biggest tool” to combat wage theft, she said.

Contact Bailey Schulz at bschulz@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0233. Follow @bailey_schulz on Twitter.