Southern Nevada LGBTQ clinic growing to keep up with demand

When Rob Phoenix was growing up gay in rural Pennsylvania, he never had someone with whom he could feel comfortable asking questions about sex or his body.

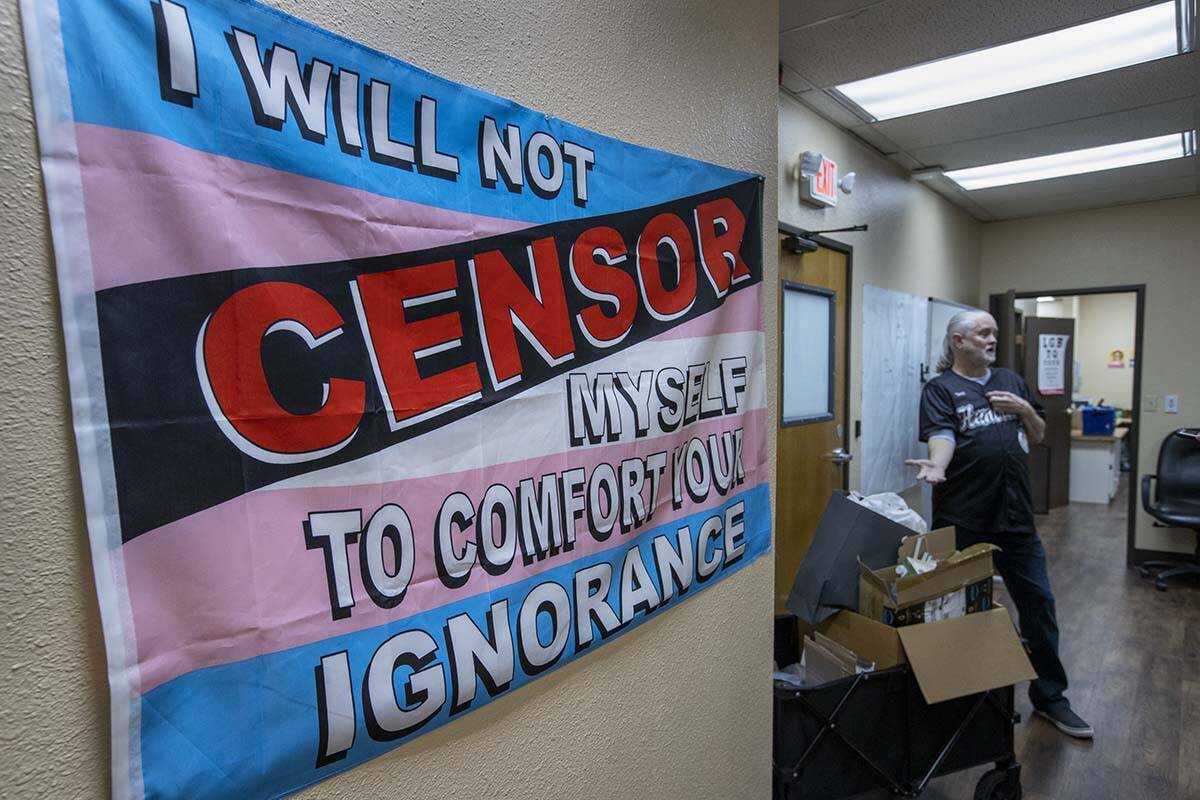

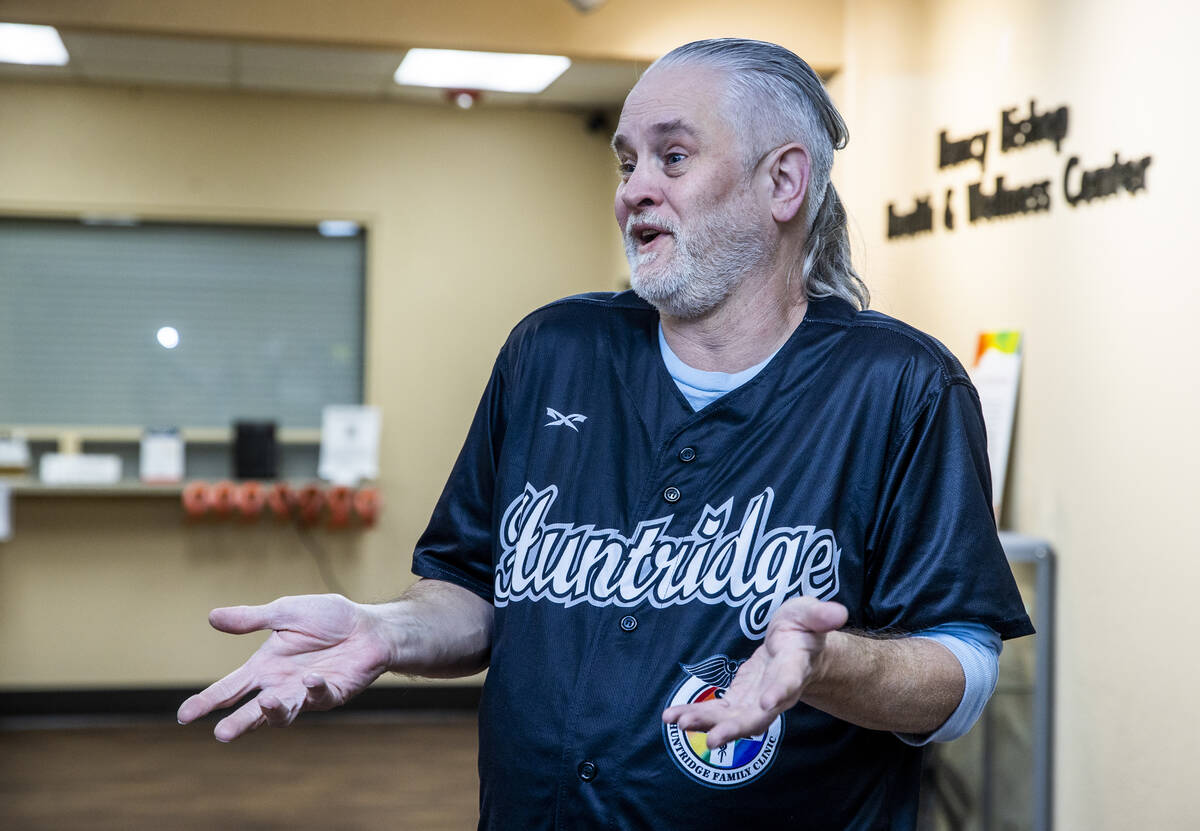

Today the 56-year-old family nurse practitioner is doing his best to ensure that others won’t face that situation through his Huntridge Family Clinic, the only LGBTQ-focused health clinic in Southern Nevada. His goal is to provide care for all of a patient’s needs regardless of who they are, their needs or ability to pay.

Now, his small clinic on East Sahara Avenue is having a big impact on the LGBTQ community.

Huntridge fills a niche for Nevadans who may struggle to find health care providers who understand and are willing to meet their needs. Since opening in 2013, the clinic has evolved to keep up with demand and provide holistic care to some of Nevada’s most vulnerable residents.

“Everybody can feel comfortable talking about what they’re doing in the bedroom or in the car or behind the bar or wherever they’re doing whatever they’re doing,” Phoenix said.

Expansion plan

Huntridge staffers provide primary care, HIV prevention and treatment and hormonal care to patients, roughly 80 percent of whom identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or transgender.

“Without them, I don’t know what we would be doing,” said Laura Hernandez, the director of the Nevada Alliance for Student Diversity, a student and parent advocacy organization promoting gender and racial diversity. “I don’t know where our families would be. I don’t know how we would manage.”

An estimated 5.5 percent of Nevadans identify as LGBTQ, the third-highest rate in the nation behind Oregon and Washington D.C., and Clark County is home to 78 percent of queer Nevadans, according to the UCLA School of Law’s Williams Institute.

Phoenix was named the Southern Nevada Health District’s 2018 Public Health Hero for his work at the clinic and with the district’s Office of Epidemiology and Disease Surveillance.

The clinic opened in 2013, operating on Monday mornings with two exam rooms in a 1,000-square-foot space he shared with the now-defunct Huntridge Teen Clinic. Three years later, the family clinic moved to another building, and in January 2021, it moved to a more spacious location at 1820 E. Sahara Ave.

The clinic is a Southern Nevada leader in HIV research and distribution of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). The clinic has 19 staffers, sees 20 to 40 patients per day and serves around 700 to 800 HIV prevention patients as one of the largest such providers in the state, Phoenix said.

In February, the clinic spent $3,000 to pay rent for patients. It spent another $3,000 some weeks ago to pay for a patient’s monthlong stay getting sober at an in-patient rehabilitation facility, he said.

Huntridge takes commercial insurance and Medicaid, offers a sliding-scale cash pay system for those without insurance and participates in the federal assistance Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. The clinic has even accepted tamales as payment, when during Christmas one year a patient said she couldn’t afford her co-pay.

Such expenses come with the territory. As Phoenix said, “I am not in this business to get rich. I am in this business to provide services, and to me, that is a cost of business.”

‘It’s the place to go’

Most of the clinic’s patients come by word of mouth or referrals from other providers. Huntridge also partners with the LGBTQ Center of Southern Nevada for HIV and STI infection testing and treatment and the center’s substance use program.

The clinic’s partnerships with community groups and individual leaders are a strength, said UNLV psychology professor Rainier Liboro, who studies health disparities in racial, sexual and gender minorities and is a research lead at a mental health research lab. Liboro recently partnered with the clinic to find willing participants in two studies of gay and bisexual men living with HIV.

Liboro said the clinic models how an LGBTQ-focused clinic can work, a community beacon to be replicated and supported.

“As an openly gay man, I’m more comfortable seeking support from a health care provider that understands and knows my needs without me having to explain it to them, or having to specify what would make me more comfortable,” Liboro said. “That’s not a small thing. That’s a huge thing.”

Hernandez, the diversity alliance director, said the clinic is at the top of the list she keeps for referrals.

“Everybody’s going there because it’s the place to go,” she said.

Hernandez’s daughter is a patient at the clinic. Her daughter began transitioning several years ago and at the time was prescribed puberty blockers, giving her daughter some time to work through her transition before deciding whether to start hormone replacement therapy. Phoenix allowed Hernandez to pay cash at a significantly reduced cost for her daughter’s lab work when Hernandez lost health insurance in a job change. Puberty blockers and labs for ongoing care are “outrageously expensive,” she said.

Without that option, Hernandez said, her child wouldn’t have gotten the care she needed.

“People don’t really understand the way that adolescents’ mental health is affected when they start going through puberty that makes them feel like their body’s betraying them,” Hernandez said. But Huntridge does understand, she said.

Supply and demand

With demand high, patients sometimes face long wait times. While the clinic has taken steps to streamline the patient care process and wait times, the clinic is often booked a few months out for new patient visits, Phoenix said.

Hernandez said she knows multiple families who were frustrated with wait times and sought care elsewhere, only to find themselves back at the clinic several months later because they felt unsafe at the new provider. There’s an overwhelming need for more queer care, she said.

“I wouldn’t want to be in a position of having to try to figure out how to create the infrastructure to meet the demand that’s there,” she said. “It’s hard work, and I think that they’re doing a good job.”

She said there are some 300 families in the alliance’s network and somewhere between 50 to 80 of them leave the state to places such as California and Colorado for medical care.

Krista Whitley speaks glowingly of the clinic, thinking highly enough of the care her 12-year-old son, Kai Castellarin, received at Huntridge to leave a four-paragraph review on the clinic’s Facebook page on April 1, 2021. Kai came out as a trans boy to his family on Valentine’s Day last year, and Whitley scheduled an appointment for 45 days later at the clinic.

Kai, then 11, left his first Huntridge visit feeling confident, validated and “like he had the tools in his toolkit that he needed to really live his truth,“ his mother said.

They’re now one of the families who travels for care — Whitley said she can afford to travel to Beverly Hills every three to six months so Kai can have more tailored care with shorter wait times.

Still, she considers Phoenix a community trailblazer and continues to recommend the clinic as “absolute choice number one” to local families seeking LGBTQ-friendly care.

She credits Phoenix and the clinic for empowering Kai, a 12-year-old honor student on his middle school’s boys soccer team and a founder of the school’s pride club.

“Sometimes it just takes that one positive experience to really lay a good foundation for these kids, because a negative experience can be so disheartening,” Whitley said.

Here to stay

Phoenix hopes to expand Huntridge’s offerings.

He is awaiting regulatory approval to open an in-house pharmacy. He has some unused office space he envisions could house a behavioral and mental health component. And he’s looking for a building to create a sobering center, where substance users can wait out their intoxication in a safe environment rather than a potentially costly emergency room visit.

Phoenix said he wants to Huntridge to become more efficient at the things it already offers, but he finds it hard to say “no” to expanding the services the clinic offers.

Las Vegas needs more housing and substance use resources beyond the “revolving doors” of in-patient care facilities, he said. The valley also needs more health care providers that focus on the disparities experienced by LGBTQ people, particularly people of color, he added.

“I have a lot of patients that come in and they’re like, ‘Nobody’s ever had a conversation with me about my sexual health,’” Phoenix said.

John Waldron, CEO of the LGBTQ Center of Southern Nevada, said queer people often struggle finding medical providers who are qualified and knowledgeable to meet their health needs.

A 2019 Human Rights Campaign survey found 56 percent of lesbian, gay and bisexual people and 70 percent of transgender people reported experiencing discrimination from health care providers.

Phoenix, Waldron said, is committed to helping transgender and intersex Nevadans and to teaching other practitioners and community members.

Huntridge hosts nursing, medical and pharmacological students and residents to work out of the clinic. Phoenix said he wants to educate students on HIV treatment and prevention, gender-affirming care like puberty blockers and hormone replacement therapy and other pertinent care. Then, he said, they will be equipped with the knowledge and skills to effectively help queer patients and potentially open their own LGBTQ-focused clinics or practices.

Silver State Equality director Andre Wade said Phoenix’s efforts toward closing the gap in queer-centered medical care are making a difference.

“Even though it’s this one clinic that is overloaded with people trying to get services, at least it’s there,” Wade said.

This story has been updated to clarify a previous statement about puberty blockers and lab work.

Contact Mike Shoro at mshoro@reviewjournal.com. Follow @mike_shoro on Twitter.