Disabled veteran killed in police shooting

Stanley Gibson was trying to find his way home.

The 43-year-old disabled war veteran was off his anti-anxiety medication and stricken with paranoia as he headed back to the apartment where he and his wife recently had moved.

In his confusion, Gibson ended up at an apartment complex a few blocks away, prompting suspicious residents to call police.

Officers confronted Gibson in his car, which was pinned between two patrol cars, ultimately firing a fatal shot. He was unarmed.

A breakdown in communication between supervisors and the firing officer might have contributed to the shooting, multiple department sources told the Review-Journal.

Early indications were that two supervisors decided to use a beanbag shotgun -- a weapon designed to subdue but not kill -- to shoot out at least one window of Gibson's vehicle. But their decision might not have been understood by the firing officer, and when one of the supervisors fired the shotgun, the officer fired multiple times in a reaction to that blast.

Department spokeswoman Carla Alston said that it would be "speculative" and "premature" to comment on those details before the investigation is over and before the department had a chance to conduct full interviews with the officers involved.

"The sheriff doesn't have all those details," she said.

Details are all that matter now to members of Gibson's family, who say the ex-soldier had been through so much for his country and received so little in return.

"I just want someone to answer," said his wife, Rondha Gibson, 48.

'A SAD DAY'

Clark County Sheriff Doug Gillespie rarely participates in news conferences immediately after police shootings. He said he was prompted to speak Monday because of the circumstances -- the fatal shooting of an unarmed man -- and because there hasn't been a coroner's inquest of an officer-involved shooting since October 2010. The Clark County coroner's inquest was the fact-finding process in which details of shootings were released to the public.

"We have not had an inquest in over a year, and I don't think it's right to wait. I want answers as much as you," Gillespie said. "Anytime we have a fatal use of force incident, it is a sad day."

But the sheriff offered little insight into the case, citing the ongoing investigation and that none of the officers at the scene had given statements.

Officers are required to give internal statements to police within 72 hours that cannot be used against them for the purpose of criminal prosecution.

Officers have stopped speaking to homicide investigators, who have been handling criminal investigations into police shootings since the beginning of this year.

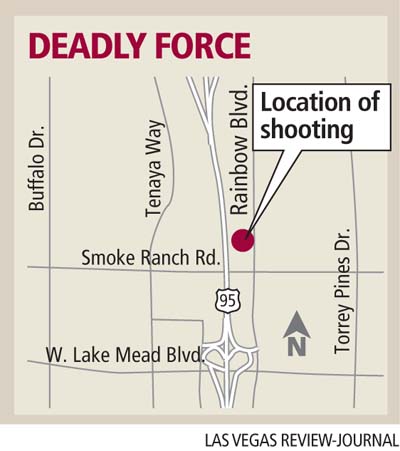

Police said officers had responded to reports of a burglary suspect at the Alondra apartments near Rainbow Boulevard and Smoke Ranch Road.

Raymond Allmendinger, 55, did not see the shooting but witnessed the preceding events.

Allmendinger said two patrol vehicles with their lights on pinned the vehicle, making it unable to back out of the parking spot.

The driver began spinning his car's wheels, he said.

"The tires were just spinning and squealing, but the car wasn't moving," Allmendinger said. "The fumes and smoke went crazy. You could not see the car. The smoke was everywhere."

Police eventually ordered Allmendinger to evacuate from his home, and as a result, he no longer could see the scene. About 20 minutes later, he heard seven or eight shots.

ANTI-ANXIETY MEDICATION

Gibson's family said he was never a threat to police. They believe Gillespie and the department have painted him as a criminal by calling him a "suspect."

"To them he's just another dead soldier or a dead black man," Rondha Gibson said.

She blamed police for using deadly force against her husband. Most of her anger, though, was directed at the Department of Veterans Affairs, which she said constantly slashed her husband's benefits and destroyed his morale.

Gibson had finished the last of his anti-anxiety medication earlier this month. Then a VA doctor canceled their appointment, she said, and refused to refill the prescription without seeing him.

By Saturday, a full two weeks without his medication, Gibson started to believe it was 1987 and spoke of searching for his father, whom he had never known, she said.

"He didn't know where he was and didn't what he was doing," Rondha Gibson said.

On Saturday morning, Gibson went outside and had a mental breakdown, screaming at cars and causing a scene, his wife said. He even began accusing his wife of conspiring against him.

Las Vegas police eventually arrived and arrested Gibson on a charge of resisting arrest.

He was booked into the Las Vegas Detention Center about 1:45 p.m. Saturday on the misdemeanor offense.

Rondha Gibson pleaded with the officers not to arrest him because he wasn't in the right state of mind.

"They said he was in a fighting stance," she said.

The officers assured her they would have Gibson placed on a 72-hour psychiatric hold, called a "Legal 2000," where a doctor could evaluate his state of mind.

But Gibson showed up at home Sunday, well before the 72 hours. He told Rondha Gibson he had taken the trash out and didn't remember going to jail.

City spokesman Jace Radke said Gibson was released eight hours after his arrest on his own recognizance and had no information indicating he was supposed to be under a psychiatric hold.

Rondha Gibson said detectives later told her the system failed her husband by not keeping him for evaluation.

She has no idea where Gibson was between 10 p.m. Saturday and Sunday morning.

LEFT HOSPITAL

Sunday was not a better day for Gibson. He twice called 911 and asked to be taken to a hospital, Rondha Gibson said.

But each time, he abruptly left without receiving treatment.

When she found out Gibson had suddenly left University Medical Center about 7 p.m. Sunday, Rondha noticed her husband's white Cadillac was gone.

She didn't hear from him until Sunday about 9:30 p.m., when he called and said he was parked outside the complex's office.

But when she checked, Gibson was nowhere to be seen, she said. That happened several times, with Rondha Gibson getting more and more frustrated. Her husband never came home.

When she turned on the TV early Monday morning, she saw reports of a police shooting at the building just north of her complex. And she saw her husband's Cadillac at the center of a crime scene.

'REMEMBER SEPT. 11'

The Gibsons' apartment on Monday felt like a soldier's home, although they had occupied it only for a few days.

A "Remember Sept. 11" reminder sticker is displayed on their fridge. The background of a photo of the couple is an American flag.

As family and friends gathered in the home Monday afternoon, faith in the country seemed to be waning.

Christopher Murray, a childhood friend who attended Eldorado High School with Gibson, said his friend felt abandoned by the VA and the country he served.

Gibson lost most of the control on the right side of his face because of cancer, which the family thinks he received from exposure to depleted uranium in the Gulf War.

Each year, the VA slashed his benefits, Murray said.

"He would say, 'I committed my life to them and they need to honor their commitment to me,' " Murray said.

At one point during the gathering, Rondha collapsed into the arms of Gibson's brother, Rudy.

Rudy Gibson began sobbing.

"He's not hurting anymore," he said.

Murray questioned whether anyone would remember Gibson or how he died.

He pointed to the cases of Eric Scott and Trevon Cole, two men killed in separate high-profile police shootings in 2010.

"What's the end? What's it going to change, dude?" he said. "We've lost a friend, he's lost a brother, she's lost a husband, and what's it going to change?

"In a month, he'll be a statistic, and no one will remember."

Reporters Lawrence Mower, Antonio Planas, Brian Haynes and Keith Rogers contributed to this report. Contact reporter Mike Blasky at mblasky@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0283.

DEADLY FORCE

Review-Journal investigative report on officer-involved shootings