Killer says deadly Hilton blaze in 1981 ‘wasn’t meant to hurt anybody’

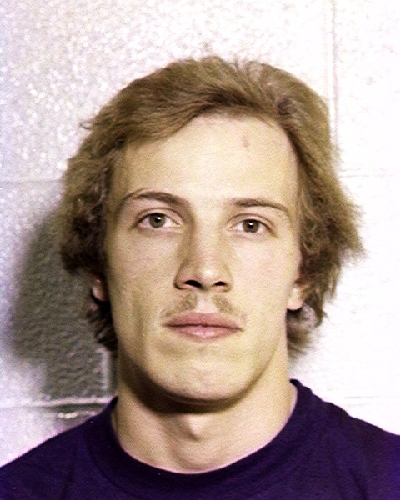

Philip Cline tries not to think of that day 30 years ago. The sky was ablaze. Hundreds were hurt. Eight people were dead. He was to blame.

As he watched the Las Vegas Hilton burn the night of Feb. 10, 1981, the 23-year-old figured he had it coming.

He had stolen cars. He had stolen money. He was probably headed to prison one way or another.

But he never wanted to hurt anyone, and he wasn't a cold-blooded killer.

That's what still bothers him three decades later.

During a recent interview in a drab cinder-block meeting room at High Desert State Prison, where Cline is serving eight consecutive life terms, he emphasized how sorry he was for what happened and insisted he never intended to hurt anyone.

"A lot of people, I think they think I did it on purpose, and it wasn't done on purpose," he said. "I did it. I'm responsible for it. I admit it. I did it. But it wasn't meant to hurt anybody or kill anybody. That's the one thing I want to get across."

But for many, Cline's words ring hollow.

Retired Las Vegas police homicide Detective Chuck Lee, who got Cline's confession during a polygraph test, always believed Cline intentionally set the deadly fire, perhaps as part of a homosexual encounter in that eighth-floor elevator lobby.

Yet even if Cline's new story is taken at face value, the dangerous nature of his act speaks for itself.

"He set the fire. Only he knows his intentions," Lee said. "You set a fire in a crowded hotel ... what do you expect?"

Petty crimes preceded fire

The son of a career Air Force veteran, Cline left his Bay Area home about 1980 and moved to Las Vegas, a glittering town he had once run away to as a young teen.

The former altar boy was hardly an angel, committing petty crimes as often as he changed jobs.

He bounced around casinos, including the El Cortez and MGM Grand, before becoming a $39-a-day busboy at the Hilton about six weeks before the fire.

By then his growing rap sheet included charges of possessing stolen property, possessing burglary tools and embezzlement. That last charge involved the theft of $100 while he worked at the El Cortez, a crime he pleaded guilty to less than two weeks before the fire.

On the night of the fire, Cline was working as a busboy in the hotel's east tower.

Now 53 and balding, Cline revealed he never had been completely honest about what happened that night. He never told his family, and he never told his lawyers.

But now, he wants everyone to know the truth.

Cline said he was on his break when he sat on the couch in the elevator lobby to smoke a marijuana cigarette mixed with cocaine and dipped in PCP that his roommate had given him.

Cline's roommate had warned him not to smoke it all at once -- advice he ignored.

"Why did I mess with that stuff that I shouldn't have?" he said. "Messing with the drugs. I couldn't handle it. I was weak-minded."

Then, "for no reason, I just, I had his lighter, and I lit the curtains on fire," he said.

The flames grew fast, climbing the curtains and igniting the couch.

Cline said he called the hotel operator to report the fire. He remembered a security guard stopping by with a fire extinguisher that didn't work.

The guard left to find another one, and the flames kept growing. Cline banged on room doors to warn guests before heading downstairs to his work area.

"The smoke on the ceiling started getting darker and darker and lower and lower,'' he said. "I got scared."

He joined other workers in the employee parking lot and watched the brilliant flames climbing the side of the building, then the largest hotel in the world with 2,783 rooms.

Panic set in as flames climbed into the night sky, rekindling memories of the deadly MGM Grand hotel fire less than three months earlier.

Shortly after 8 p.m., firetrucks surrounded the burning hotel. Guests broke windows and cried for help. Bedsheets tied into makeshift ropes hung from windows. Helicopters plucked people from the rooftop.

Inside, hotel workers told people to stay in their rooms with towels under the doors as the hallways filled with black smoke.

Seven people died from smoke inhalation, three of them in the eighth-floor elevator lobby where the blaze began. Another victim, Bruce Glenn, 47, of Plymouth, Minn., fell or jumped to his death from a 16th-floor window.

Also killed in the fire were Dennis McFarland, 32, Boone, Iowa; Frank Greenfield, 22, West Bloomfield, Mich.; Robert Leach, 54, Honolulu; Harry Gaines, 69, and his wife, Lorraine Gaines, 67, Los Angeles; Zeny Carvalho, 64, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; and Jack Turinsky, 41, Anchorage, Alaska.

About 200 others were injured in the blaze.

As he watched the horror unfold, Cline thought to himself that he had it coming.

"I was thinking, you know, all the stuff I had done prior -- stealing cars, stealing money -- was all coming back on me. When you do bad stuff, karma comes back on you. You don't get away with nothing, you know. It just comes back and gets you."

Cline filled out three written statements that night, one for the hotel, one for fire investigators and one for police. It was the last one that made him a suspect.

In all of the statements, he wrote how he had discovered the fire, called the operator and banged on doors. He also wrote that he had grabbed a wastebasket and filled it with water in an attempt to quell the flames.

But in his statement to police, he made what authorities considered a Freudian slip.

"I grabbed a trash can and filled it up with fire, and I put the couch out & then I went to get some more fire (the word was crossed out) water to put the curtain out," the statement read.

Homicide detectives questioned him the next day.

Woman's testimony sealed fate

After a polygraph test, Lee knew Cline wasn't being completely honest.

The veteran homicide detective called his bluff, and Cline broke down: He said he was on the couch having sex with a man named Joe. They were smoking a marijuana cigarette that accidentally caught the curtains on fire.

"I never believed it was an accident," Lee said.

Investigators tried to replicate the cigarette igniting the curtains and couldn't. They couldn't find the mystery man called Joe.

Some believed Cline set the fire so he could look like a hero. Others believed he was a serial arsonist who had set other fires in the Hilton that night and was responsible for recent fires in other hotels, including the MGM Grand fire that killed 87.

Cline said he had nothing to do with any of those other fires, and he insisted what happened at the Hilton was never meant to harm.

So why not tell detectives the truth?

"I didn't want to face the truth. I didn't want to tell people that I was responsible for doing that. I was scared," he said. "I thought if they didn't know the truth, I'd be all right, if that makes any sense."

Prosecutors charged Cline with arson and eight counts of first-degree murder.

The jury endured a seven-week trial that included plenty of tedious technical testimony about the fire, flames and arson. But it was the testimony of a red-haired woman early in the trial that sealed Cline's fate, two jurors recalled.

David Kelley, the then-36-year-old jury foreman, said he awoke from a dead sleep one night when the case crystallized in his mind.

The woman had testified about walking down the hall to get ice and passing a man on a hotel phone reporting a fire. But she saw no sign of fire until after she returned to her room with the ice, said Kelley, who had watched the flames crawl up the Hilton while he was working at McCarran International Airport.

"He called it in and then started the fire," he said. "He wasn't trying to hurt anybody. He was trying to be a hero."

Kathy Zeller, then a 32-year-old accountant, said the woman's testimony was key in convicting Cline.

"He probably was looking for a little stardom," Zeller said. "He got it, but not in the right way."

Hilton paid $16.5 million

Prosecutors pushed for the death penalty.

Cline's lawyer, Kevin Kelly, argued that the hotel should share most of the blame for the deaths because of its failure to maintain basic fire safety devices such as fire alarms and sprinklers.

"To say now that Philip Bruce Cline knowingly created the risk of death to more than one person is to blind oneself to the negligence displayed by the Las Vegas Hilton Hotel," Kelly wrote in court papers.

The Hilton would eventually pay $16.5 million of a $22.8 million settlement to end a federal court lawsuit filed by fire victims naming the hotel and various companies responsible for its construction and furnishings.

Jurors in the criminal case weren't swayed by Kelly's argument about the hotel being responsible, because the building was up to the current fire codes, the jury foreman said.

When it came to deciding Cline's fate, the jury settled into a debate over whether he deserved to be a free man again, he said.

"We couldn't go with the death penalty, because we didn't think he did anything to hurt anybody," Kelley said. "But we gave him no parole because after MGM he should have known how disastrous hotel fires could be."

The jury spared Cline's life, but in giving him eight consecutive prison sentences of life without parole, it all but assured he would die behind bars.

"He's in the place he needs to be," said Zeller, who now works in the Hilton accounting department.

Kelly said his former client had many issues to raise on appeal, including his lack of a lawyer when he gave his confession, but for some reason Cline was never given an attorney to file an appeal.

Kelly said Cline deserves a chance at freedom, but he doubted the governor, attorney general and state Supreme Court justices who comprise the Pardons Board would ever release someone convicted of killing eight people in a Las Vegas hotel fire.

His former client never helped himself, either.

"Philip Cline was his own worst enemy. There were a number of things he said before and after the trial that just didn't make sense," Kelly said. "He just couldn't tell the same story twice."

Yet Cline said he still hopes the Pardons Board will give him a chance at freedom.

"I don't think I deserve to die in here, but I did what I did. I'm responsible for that," he said.

During his nearly three decades in prison, Cline has gotten his high school diploma and has kept busy, avoiding the torment of reliving that night in his mind. He works sorting casino playing cards and repackaging them to be sold to tourists.

He has considered reaching out to the victims' relatives. Once he asked a friend to find their addresses, but the friend talked him out of it.

Even now he struggles to find the words he would say to the families he changed forever.

"It bothers ... me, just knowing that I can't undo what I did," Cline said. "I can't bring back them eight people. And that's what messes with me the most, is I can't undo what I did and bring them eight people back to their families. ... There's nothing I can say or do that will bring them back."

After the emotional interview, the prison guards looked at each other and made a note to put Cline on suicide watch the rest of the day, and again on Thursday -- the anniversary of the fire.

Contact reporter Brian Haynes at bhaynes@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0281.