Study: Las Vegas deportation program ‘most targeted’ toward major crimes

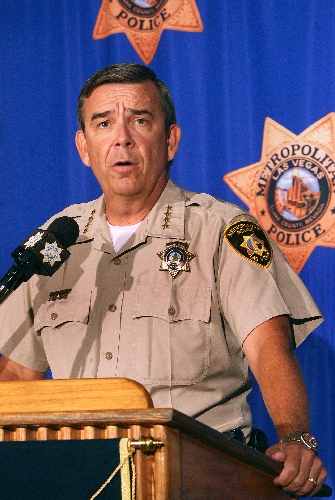

When Sheriff Doug Gillespie decided to support a controversial partnership between his department and federal immigration officials, he promised the program would target for deportation inmates arrested for "higher-level" crimes.

Over the partnership's more than two-year history, he has mostly made good on that promise, according to a new study.

While some of the nation's law enforcement agencies, particularly in the Southeast, are turning over to federal authorities illegal immigrants who commit even minor offenses, the Metropolitan Police Department has focused on deporting serious criminal offenders arrested for felonies, according to the study, released Monday by the Migration Policy Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based nonpartisan think tank.

Among law enforcement agencies studied by the institute, Las Vegas' program was found to be the "most targeted" toward serious offenders.

"This shows that the way we run the program has been consistent since we started," said Lt. Rich Forbus, who manages the local program. "We will continue to manage it the same way."

The study examined seven of the more than 70 jurisdictions that have entered into "287(g)" partnerships with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The partnership -- named for its corresponding section of the federal Immigration and Nationality Act -- grants some federal immigration enforcement powers to state and local law enforcement officers.

In Las Vegas, the partnership allows specially trained corrections officers at the Clark County Detention Center to identify immigration violators and place "immigration detainers" on them. The detainers let local law enforcement hold deportable inmates after they otherwise would be released so immigration officials can take custody of them.

Critics have said such programs could lead to racial profiling and harm relationships between police and immigrant communities.

The study was based on visits and interviews in Las Vegas; Cobb and Gwinnett counties in Georgia; Frederick County, Md.; Los Angeles County, Calif.; Prince William County, Va.; and the state of Colorado. Researchers also analyzed data provided by ICE on all people processed through the program in all participating jurisdictions.

Enforcement varied widely in the jurisdictions studied. Several agencies in the Southeast were turning over to federal officials every illegal immigrant taken into custody, despite federal guidelines stating the program's primary focus should be on those charged with crimes such as rape, murder, robbery or drug offenses.

In Las Vegas, more than 70 percent of illegal immigrants detained for transfer to federal authorities had been arrested for serious crimes. That figure was less than 10 percent in several other jurisdictions.

The study "highlights the absence of a clear and comprehensive interior immigration strategy," said Randy Capps, senior policy analyst for the institute and co-author of the study.

Conflicting messages from the U.S. government and local political pressure may account for discrepancies between jurisdictions, the study said.

In Las Vegas, "political considerations were not the primary motivation" to enter into the 287(g) agreement, the study said.

Gillespie has long said he pursued the partnership because he wants "to know who is being booked into our jail." Previously, officers did not have the ability to check the immigration status of inmates and the sheriff's department had to rely on ICE officials to investigate and place detainers on potential immigration violators. ICE officials were not consistent in their approach, Gillespie said.

Twenty percent of inmates referred from Las Vegas to federal authorities were booked into jail on traffic-related charges, the report said. But Forbus said the department typically would only refer such inmates to ICE if they had a police record that included more serious crimes.

The department also refers for deportation a majority of illegal immigrant inmates arrested for domestic violence and for driving under the influence, Forbus said.

"Our goal is to make this the safest community in America," he said.

Since the program began in late 2008, through the end of 2010, Las Vegas corrections officers placed immigration holds on 5,184 inmates, Forbus said. They did not place immigration holds on another 2,804 inmates found to be in the country illegally because they had no prior criminal history and had been booked on only minor charges.

Since the program began, 2,867 of the inmates referred from Las Vegas to federal authorities were removed from the United States, ICE said. Immigration cases can drag on for months or even years.

Community members in Las Vegas and Los Angeles County didn't express as many serious concerns about the 287(g) program as in other jurisdictions, the study said. Both jurisdictions target serious offenders. As a result, they "give immigrants less reason to believe that ordinary interactions with police will lead to detention and removal," the study said.

Michael Flores, an immigrant rights activist with ProgressNow Nevada, said Las Vegas "does a great job of implementing 287(g)."

"We have to understand that policies are needed to weed out the bad apples," he said. "I don't want some serious felon living next door to me, either, whether they have documents or not."

Flores said the local department does a good job reaching out to the local Hispanic community and explaining the program. "At the end of the day, I do believe they are running it well," he said.

But Fernando Romero, president of Hispanics in Politics, said he still has "many concerns" about the program. He worries about the 30 percent of inmates arrested on less serious crimes who are referred to ICE, and says local police haven't been responsive enough in supplying statistics about the arrests to the community.

"We're looking at individuals who have led relatively clean lives, have children in school and go to church," he said. "We support getting rid of the criminal element, not law-abiding citizens who fall into the net."

Contact reporter Lynnette Curtis at lcurtis@reviewjournal. com or 702-383-0285. The Associated Press contributed to this report.

287(g) study by Migration Policy Institute