Deaths of 2 homeless men in Las Vegas underscore danger of streets

The so-called Corridor of Hope — the area where most of Las Vegas’ social services for homeless are clustered — stirs shortly after dawn.

Beeping blue-and-gold RTC buses pick up sleepy-eyed riders as the area’s homeless residents wait for breakfast at Catholic Charities of Southern Nevada. Others peer out from behind the Velcro flaps on their multicolored tents.

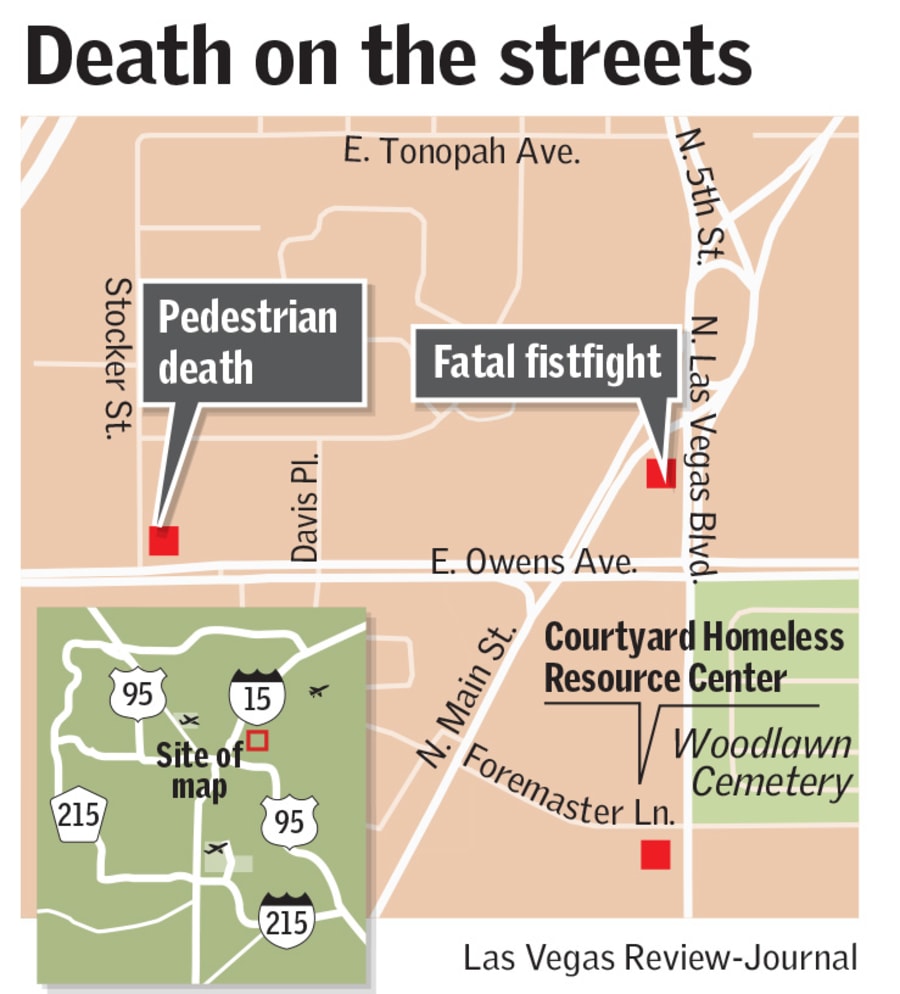

But the routines of another day on the streets can quickly give way to mortal danger, a message freshly delivered to residents this month through the deaths of two homeless men within a few blocks of the central gathering point along Foremaster Lane and Las Vegas Boulevard North.

They died in very different circumstances: One was run down by a vehicle while crossing a busy street in a marked crosswalk; the other was brutally beaten to death in a fistfight with a fellow vagabond.

Some homeless residents admit to being unnerved by the back-to-back fatalities, but others say they simply underscored a central truth of life without permanent shelter.

“There ain’t no safety on the streets,” said Kelon White, 31. “You’ve got to do what you have to do to survive.”

The first death occurred about 6:30 a.m. March 12, when a man known to social workers and acquaintances only as Nick was struck by a white pickup as he crossed Owens Avenue in a crosswalk, apparently headed from the Salvation Army on the other side of the road, North Las Vegas police said.

Spokesman Eric Leavitt said that the driver was headed to work and police don’t believe speed or impairment were factors. As of Friday, it was unclear if the driver had been charged.

Three days later, around 1 a.m., officers responded to reports of a bloody fistfight near a Super Pawn store at 1611 Las Vegas Blvd. North. When they arrived, they found a homeless man dead and his alleged attacker at a nearby street corner, pacing back and forth, flailing his arms and screaming obscenities, according to his arrest report.

Armed and alarmed

At the corner of North Las Vegas Boulevard and Owens, outside the Super Pawn, a homeless man sat by a utility box Thursday, eating a plate of orange chicken and rice. He declined to give his name but said he stays nearby and saw the ambulance respond to the killing.

“I’m shook up. We don’t know who to trust,” he said. “I have a knife for protection; a lot of people I know have knives.”

But Jeremiah Martinez, 41, who was camped out with other homeless men in a dirt lot a few blocks away, said violence isn’t his worst fear.

“When we’re out here, we choose to be here,” he said, hitting his marijuana pipe as he sat under a blue tarp. “Our biggest fear is dying without nobody knowing.”

That is so far where Nick’s death falls. As of Friday afternoon, he had not yet been identified by the Clark County coroner’s office.

Nobody in the area seems to have known him well, though several residents said they often saw him around.

Juan Salinas, director of social services for the Las Vegas Valley’s Salvation Army, said the organization doesn’t demand official identification before providing services.

“And if they don’t have an ID and just use our Clarity cards, they don’t have to provide proof of their name,” he said, referring to the cards the nonprofit issues to clients to enable them to access social services in the area.

In similar cases where a homeless person can’t be identified, the Salvation Army often holds a service at the group’s chapel, he said.

Salinas said he and other workers remind clients to be careful but acknowledged that those warnings only go so far.

‘It’s a hard thing’

“On the streets, it’s something you can’t really control. It’s a hard thing that’s out there,” he said. “The main thing is for clients to be aware of their surroundings.”

Unlike Nick, the man beaten to death behind the Super Pawn was identified within days — 23-year-old Anthony Giovanni Zambrotto.

But despite having an identity, little is known about how he ended up living on the streets of Las Vegas.

His mother, Kandi Hendricks, who lives out of state, declined to comment for this story. She has raised a little more than $1,200 through a GoFundMe account to pay for his services and care of his remains. His father, Philip Zambrotto, lives in Las Vegas but did not respond to the Review-Journal’s requests for comment.

But Michael Russell, Zambrotto’s former case manager at Freedom House Sober Living Las Vegas, remembered him as a “funny, good-hearted person.”

Russell said Zambrotto was released on parole in 2016 after serving time for attempted battery with substantial harm and was struggling to get a handle on his addiction to Mucinex DM.

“He had a lot of demons inside of his mind, and that’s why he was where he was,” he said.

Russell said he last saw Zambrotto about a year ago at a bus stop on Spring Mountain Road and Decatur Boulevard. He had a gaping gash in his head.

‘Thought he was Hulk Hogan’

He said Zambrotto told him that he had gotten beat up and was staying at a group home on Frontier Street.

“He thought he was Hulk Hogan. … I used to tell him, ‘You gotta be careful, someone’s gonna hurt you,’” Russell said.

“He used to think he was untouchable. He was just a little bean pole, a skinny guy who thought he was Superman,” Russell said. “He used to button his shirt all the way up to the top, too. He always had this image that he wanted to be like a badass, like an Italian mobster.”

The case manager said that despite Zambrotto’s tough exterior, he had a lively sense of humor.

“He was a good person, somebody that screamed out for help,” he said. “And there’s just not enough of it. There’s not enough help for people who need it.”

The suspect in Zambrotto’s death, Eddie Lee Jackson, 38, also was a familiar face in the neighborhood. He remains in custody at the Las Vegas Detention Center.

Several male residents at the Courtyard Homeless Resource Center said they knew Jackson and expressed empathy for him despite the brutality of the crime.

“He suffers from a mental illness,” said Lavelle Smith, who has been on the streets of Las Vegas for about three years. “He just be going in and out sometimes. He wasn’t in his right mind when that happened. He is a good person.”

“Everybody up here has something going on, but at the same time his is a little bit rougher.”

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @brianarerick on Twitter.