Hospital heroes offered aid, comfort after Las Vegas shooting

The bus that pulled up to the main entrance of Desert Springs Hospital Medical Center the night of Oct. 1 was more ambulance than express. It disgorged 25 to 30 people injured in the mass shooting at the Strip, about half of them so badly hurt they had to be carried through the main entrance.

Emergency room clinical supervisor David Barrett, who was standing outside the entrance using his cellphone when the bus arrived, immediately took on the role of hospital attendant. He guided injured concertgoers — half with gunshot wounds, others cut, scraped or hit by shrapnel — to the emergency waiting room.

“There were a lot of people that were using other people as crutches,” he recalled.

Barrett was one of countless employees at Las Vegas Valley hospitals who leaped into new roles following the massacre at the Route 91 Harvest festival. Others did the same jobs they normally do but with a fevered repetition they could never have imagined.

While the surgeons who saved lives that terrible night have rightly been lauded, by President Donald Trump among many others, many other faceless hospital heroes have not. Here are a few of their stories:

Searching for loved ones

The madness wasn’t confined to the operating bays or even the emergency rooms. As doctors triaged the wounded, workers came from every corner of the hospital or rushed in from home and did anything they could to assist.

Shana Tello, director of medical staff services at University Medical Center, spent only two hours that night ensuring that the hospital had enough specialists on hand because so many volunteered. Through the rest of the night and morning, she tried to help friends and families find their loved ones.

She first helped a woman covered in so much blood that Tello thought she had been shot. The blood, it turned out, was from her best friend, who had been hit in the face. The woman wanted to know whether her friend was in the hospital and, more importantly, whether she was alive.

The woman’s name was not registered, so Tello took a photo and began asking questions of the trauma staff.

She then visited several patients’ rooms before finding a woman whose face was covered.

“I then leaned over to the patient and looked at the photo trying to determine if it was her,” Tello told the Las Vegas Review-Journal. “It was difficult since her face was covered, but then I kind of leaned down and asked the patient her name. She shook her head to respond it was her!”

Tello raced back to the first woman to say her friend was alive. She later met her in person.

“I went and visited her when she was transferred to another unit. I told her this story, and we both cried,” Tello said. “She asked that I write this down in a book for her.”

‘They were all crying, nonstop’

Phone operators were often placed in the role of crisis counselors.

Emily Coyle, a communications specialist for the Valley Health System, reported for work early on Oct. 2. She said she and four other operators answered 4,400 calls that day for the system’s six hospitals – more than double the usual volume.

“It was just one call after another that morning. They all were crying, nonstop. People were trying to find their loved ones. … They sounded panicked, scared, out of breath. … I wanted to cry too, but I had a job to do.”

Trina Burrage-Simon, a supervisor of telephone operators at UMC, recalled a man who called in asking about a friend.

“Then he must have looked down because he realized he had been shot. He started yelling, ‘Help, ‘Help,’” she said. “Someone got the phone from him and brought him to a hospital.”

She later learned that he had been treated and released.

‘Standing on the edge of eternity’

In many cases, nonmedical personnel didn’t have to change roles. They just had to do their jobs over and over.

Chaplain Gary Roysen was at UMC the entire night. In the hospital cafeteria, he visited with friends and family members of victims who were receiving treatment.

“At one point, I looked around, and everyone I saw was covered in blood. They had been trying to help and were that close to being hurt themselves.”

Once, as he met with people grieving in a hallway, a man walking past angrily yelled out: “Where was your God?”

A young chaplain he had been mentoring came up to Roysen after helping people through the aftermath of the shooting and said, “You know, I go in ICU or emergency and take them by the hand, and spiritually I feel like I’m standing on the edge of eternity with them.”

Roysen said he prayed with who-knows-how-many families, including one young girl who approached him in the cafeteria and asked him to pray for her sister, who had been shot.

Later he saw the girl, and her twin sister, who was struggling to move behind a walker, as they went down a hallway.

“You remember me,” the girl said. “You prayed for my sister. Thank you. Your prayers worked.”

At St. Rose Dominican Hospitals, Sister Katherine McGrail, vice president of mission, also helped patients and their families cope with loss and tragedy. On her own time, in the days following the shooting, McGrail wondered as she read scriptures each morning how God made his presence known the night of Oct. 1.

“The presence of God was witnessed to me in seeing people’s concern for one another and how they were caring for them and worried for them,” she said.

Feeding the exhausted, grieving

Meantime, food services officials and workers prepped countless meals for the medical personnel and the growing flood of grieving or frightened civilians who were told they could wait in the cafeterias rather than the public waiting rooms.

Eric Quarles, who had just started as dietary services director at Desert Springs, was in Maryland collecting belongings at his former residence when he received a call from a supervisor about 3:45 a.m. Eastern Time on Oct. 2 telling him he had to get a crew into the cafeteria.

He did, and coffee was immediately made and water stations were set up around the hospital. A breakfast was ready to go within an hour. The lounge for first responders was stocked so they could refuel when they had a moment.

“The dietary team kept an eye for family and visitors to ensure they had what they needed, giving special desserts and treats for children,” Quarles said.

Others dealt with a river of food and donations that arrived.

Tracy Szymanski, director of Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center’s volunteer program and phone operators, arrived at the hospital in a tank top and shorts within a few hours of the shooting.

She pulled donated clothing from the hospital’s “Care Closet” so visitors wouldn’t have to walk around in blood-stained outfits. She distributed cellphone chargers from a cart.

“And then it was the food.”

By Monday morning, donations of sandwiches, cupcakes, pasta and pizza were pouring in.

‘Potato chips and Gatorade’

‘Potato chips and Gatorade’

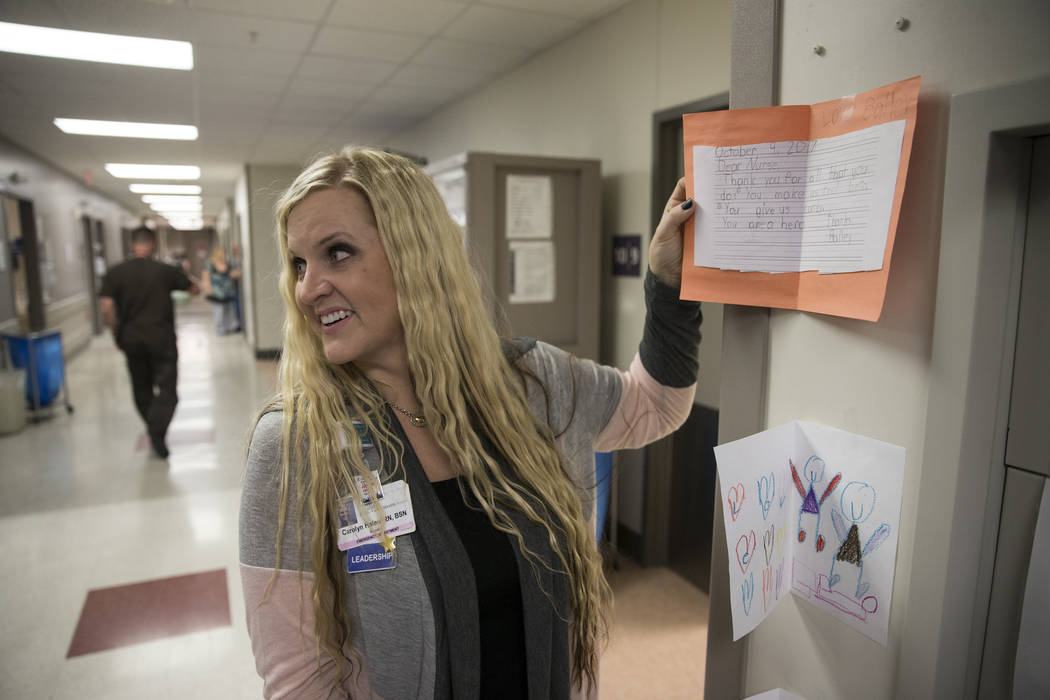

Carolyn Hafen, director of the emergency department at Spring Valley Hospital Medical Center, said she’ll never forget one donation.

“The most touching one was when this little 5-year-old boy walked in with a grocery bag that had some potato chips and Gatorade in it,” she said.

His parents said that’s what he had picked out and bought with his money.

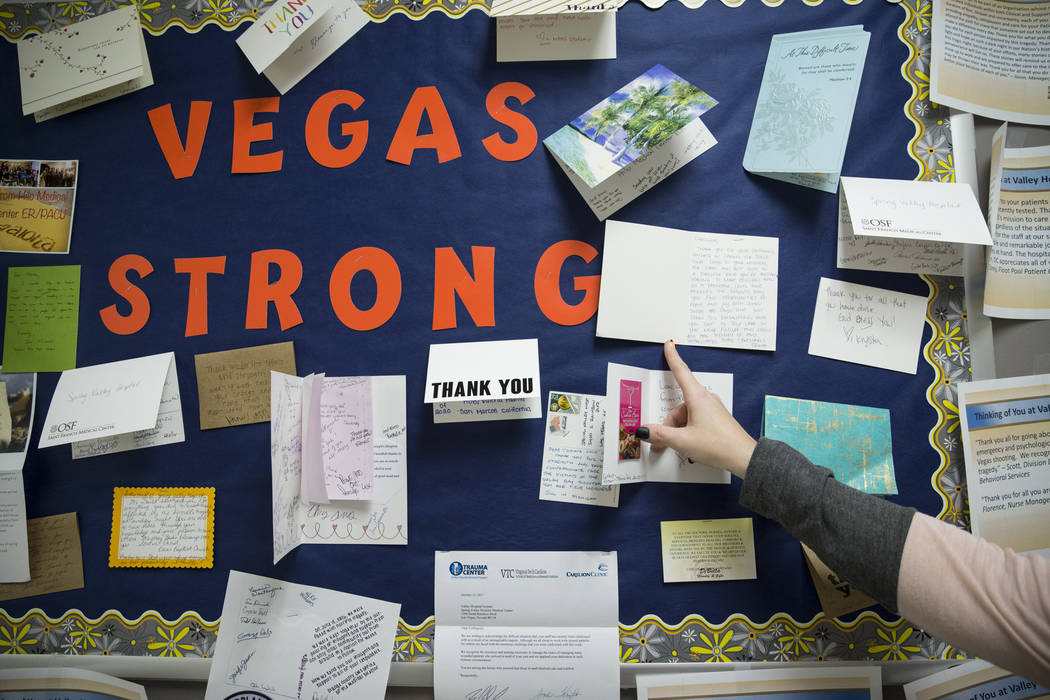

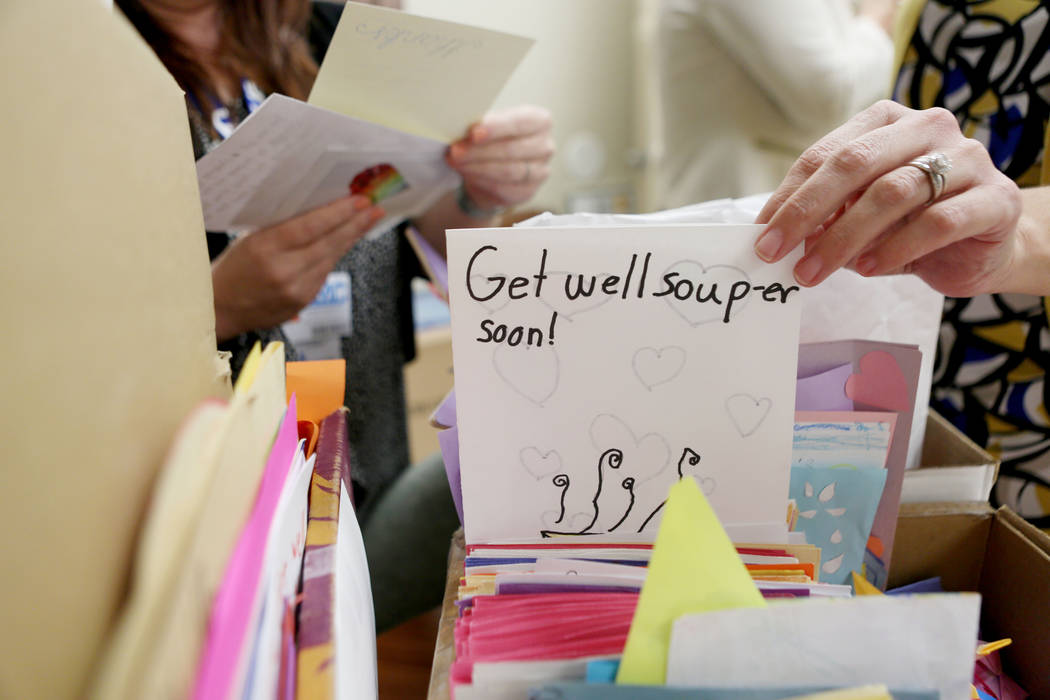

Hospitals reported receiving thousands of cards from well-wishers around the country. Some also received banners that are now hung in hallways.

Hafen also said she’d never forget a card addressed to the emergency department that had obviously been written by a child. It read:

Dear Person That I Don’t Know

Don’t be mad and don’t be sad. There are people in this world that love you.

Man’s best friend

Chris Bateman, a clinical social worker and head of the gero-psych unit at Desert Springs, recalls the FBI bringing nine therapy dogs to the hospital. He said he was in the room of an unresponsive patient when a dog was brought in.

“He was sleeping, but he must have heard everyone in his family talking about the dog that had been brought in,” he recalled. “He woke up and reached and petted the dog. It was the first time the family saw him awake. The family started crying. Nobody said a word. … Everybody started taking pictures. They seemed desperate to find a positive memory to hold on to.”

Louis Lepera, director of public safety at UMC, said security was especially tight at Nevada’s only Level 1 trauma center because there was fear that what had happened at Mandalay Bay was a terrorist attack and that UMC could be a secondary target.

In addition to his 50 uniformed men, police from the Metropolitan Police Department, UNLV and the Nevada Highway Patrol guarded the hospital.

“We even turned away a delivery truck with food because it didn’t have the proper paperwork,” he said.

‘One small thing’

Jennifer Sanguinet thought of her two children back home as she scrubbed blood off a pair of country boots.

“Being a mother, I wouldn’t have wanted to receive back those boots in that condition,” said Sanguinet, Sunrise Hospital’s infection prevention director, who worked as a family resource volunteer that night.

The boots belonged to a woman who had died. Sanguinet spent hours consoling the victim’s mother and four additional family members after they learned that their loved one was gone.

“We were using pictures of … tattoos and things,” she said of the process of confirming identities of victims, many of whom had no identification on them when they arrived.

Family member after family member approached her, asking, “Have you seen this person?”

The victim’s boots had apparently been removed during the desperate efforts to save her life. Days later, her mother contacted a colleague of Sanguinet’s, and the two promised to look. Sure enough, they found them at the bottom of a box where the hospital’s security guards kept unclaimed belongings.

There was just one more thing that needed doing. Around 8 a.m. late in the week of the shooting, Sanguinet sat in her office with hospital-grade disinfectant, removing evidence of the tragedy from the boots.

“To me, that’s kind of a closure,” Sanguinet said. “We did that one small thing for the family.”

Contact Jessie Bekker at jbekker@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4563. Follow @jessiebekks on Twitter. Contact Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702 387-5273. Follow @paulharasim on Twitter. Review-Journal staff writer Art Marroquin contributed to this story.