After Las Vegas shooting, 87 children cope with loss of parent

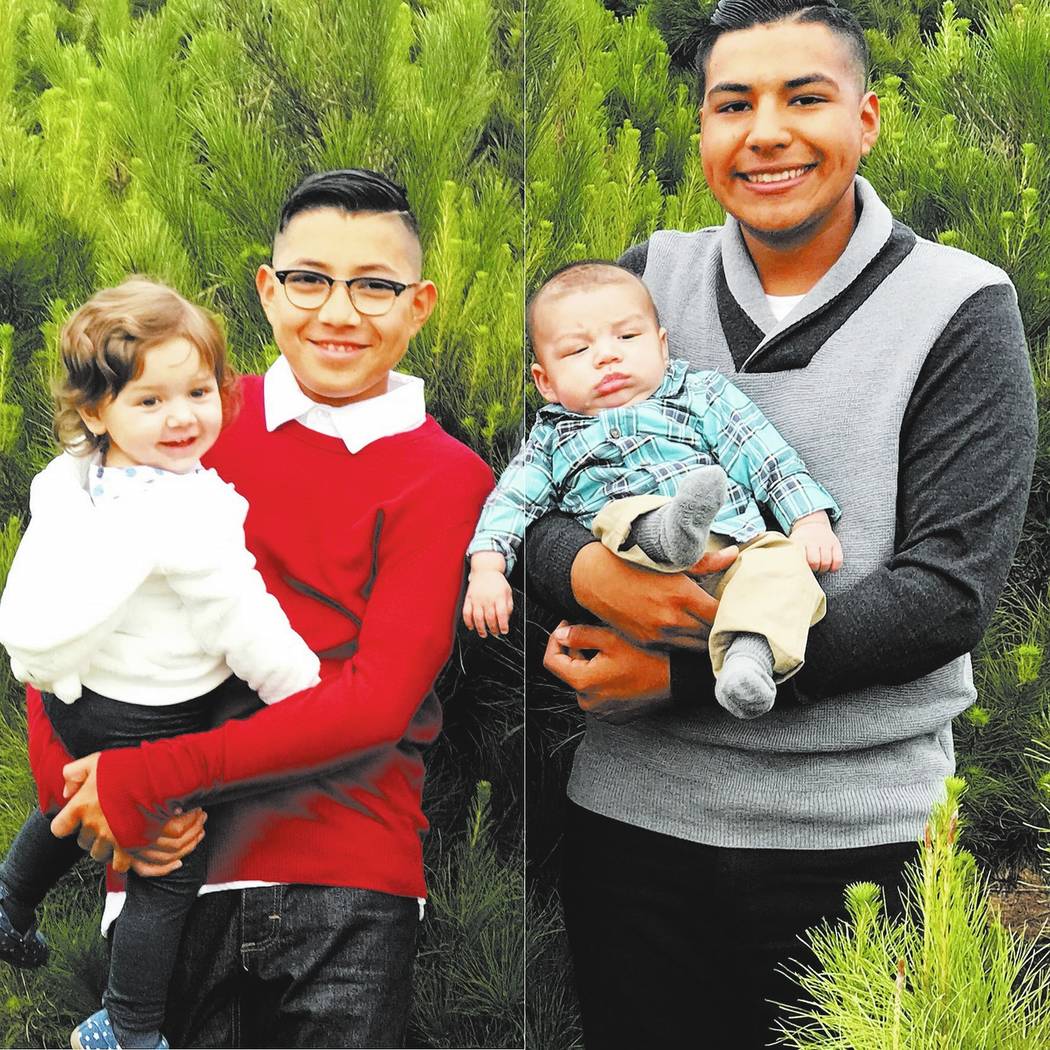

Each day during the Route 91 Harvest festival, Rocio Guillen video-chatted with her children.

The mother of four wanted to see their faces and tell them she loved them. Her youngest, Austin, was born just six weeks before the 40-year-old traveled to Las Vegas from California for the festival while still on maternity leave.

“The last morning we FaceTimed, Rocio thanked us for watching the kids and letting her get a full eight hours of sleep for the first time in a long time,” her fiance’s mother, Donna Jaksha, told the Las Vegas Review-Journal this month. “She looked so happy.”

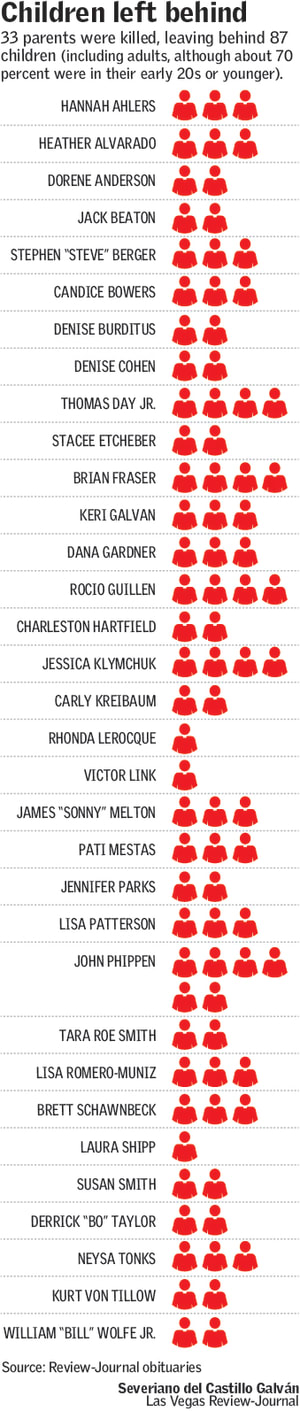

Later that night, Guillen was one of 58 people killed at the festival, and one of 33 parents who died. Together, they left behind 87 children.

Guillen’s infant son is the youngest. Some are adults with families of their own. Several are not yet teenagers.

Yet no matter the age, losing a parent in such a public and traumatic way can send a child into a tailspin, UNLV clinical psychologist Michelle Paul said.

“Children thrive on structure, predictability, routine, and knowing what to expect. That’s what creates safety and security,” Paul said. “And now a major anchor for the life of a child is gone, completely unexpectedly and out of the blue, and for no good reason. It’s going to take time for everybody to get back to a normal routine, and get a sense of what the new normal will be.”

Bedtime stories

Each night before bed, Jason LeRocque asks his young daughter, Ali, if she would like to hear a story about Mom.

The 7-year-old’s mother, Rhonda LeRocque, was one of the first people shot Oct. 1.

“I want to keep her alive in her mind,” LeRocque told the Review-Journal while sitting with Ali in their Tewksbury, Massachusetts, home.

LeRocque and his wife were married for 21 years, and he struggles with her death daily. Sometimes, though, it’s hard to tell if their young daughter fully grasps the situation. Hence the bedtime stories.

“They’re going to understand it within their developmental context,” Paul, the psychologist, said. “As we grow up and learn about life and develop a vocabulary for the gravity of the situation, we develop an understanding of what happened.”

In the meantime, children often experience grief through strong emotions — waves of sadness or anger they can’t articulate.

As time passes, “they’ll continually have questions, and when they’re ready to ask those questions, they will,” Paul said. “Especially when the surviving family members create an environment to answer those questions when they arise.”

Though LeRocque breaks down sometimes while looking at photos of his wife, he does his best to stay strong for his daughter.

“I tell her, ‘We can talk about Mom whenever you want,’” he said.

Cascade of stressors

In the weeks since the Las Vegas shooting, Robert Patterson, who lost his wife, knows his family seems OK. They get out of bed in the mornings, they still laugh and smile, and they receive constant support from family, friends and strangers.

“But we were a lot better off with Lisa here,” Patterson said while standing in his Lomita, California, driveway this month. Just inside his garage sat the mother of three’s parked car.

In the wake of the shooting, the Pattersons’ oldest daughter, Amber, withdrew from college in Arizona. Now the 19-year-old drives her youngest sibling, Brooke, 7, to school in the mornings. She makes food for everyone throughout the day. And she always tries to keep them in a good mood, like her mom did.

“My life right before all this happened was completely different. I was at school, away from everything, doing a completely different thing, and then all of a sudden the switch flipped, and now I’m here, and I’m not going to school, I don’t have a job, my friends aren’t here,” she said this month while sitting on a couch in her family’s living room. “I definitely feel like a mom now. It’s not a horrible thing. It’s just not ideal.”

Like Amber, many Route 91 victim family members likely are experiencing a cascade of other stressors that stem from a loved one’s death, said Anthony Papa, a clinical psychologist and University of Nevada, Reno associate professor.

Some examples: a loss of income; becoming a single parent without choice; having to deal with funeral homes and insurance companies.

And while Amber said her family has grown closer since her mother’s death, Papa said the consequences of the loss “can create a large amount of conflict within the family system.”

Sense of normalcy

Before the shooting, Steve Berger, 44, was already dealing with conflict within his “family system.” Berger, who was killed a day after his birthday, had recently divorced his wife, the mother of his three children, and landed full custody.

Now she’s trying to get them back.

“It’s not gotten easy,” Berger’s father, Richard, said of everything they’ve been through since his only son was killed.

Berger’s parents live in Wisconsin, where his memorial service was held. But because of the reignited custody battle, Berger’s children, ages 15, 12 and 9, are sequestered in Minnesota and couldn’t attend.

Each week, a relative travels to Minnesota to care for them. For now, it’s the only sense of normalcy they can offer because no matter who wins custody, the children’s lives will be uprooted.

“Someone is always there to get them around school and keep them company,” their grandfather said.

Healing takes time

As life moves further away from Oct. 1, Jake Beaton is stuck.

The 20-year-old’s father, Jack, was killed while shielding the young man’s mom. That his father died a hero hasn’t lessened Jake’s pain.

“He was my hero my whole life,” Jake said this month through tears. “I’m lost for words in this whole area.”

After it happened, Jake didn’t sleep for three days. Friends filtered in and out of his Bakersfield, California, home, but he’s not sure it helped.

“It’s still a nightmare,” he said.

Healing takes time. Moving forward, especially for children, can be difficult with passing birthdays, graduations or other milestones.

But it’s also important to remember everyone recovers differently. And some people will bounce back more quickly than others, which is normal, too, said Papa, the Reno psychologist.

“There’s kind of an expectation in our society that people will be significantly undone by their experience of loss,” Papa said. “You don’t have to be upset, you don’t have to be undone, and the other people around you don’t have to expect that.”

Take Braxton and Greysen Tonks for example. The teenagers’ mother, Neysa Tonks, of Las Vegas, was killed at the festival, but in a recent conversation with the Review-Journal, the two were mostly happy.

Together, they hope to “keep the party going,” as their mom would have. Her words of wisdom: “Walk it off, don’t be a hater,” and “work hard, play hard.” They channel those phrases every day.

Contact Rachel Crosby at rcrosby@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-8301. Follow @rachelacrosby on Twitter. Review-Journal staff writers Steve Bornfeld, Rio Lacanlale and Sandy Lopez contributed to this report.