Las Vegas shooting still shaping life for Summerlin couple

Night is always the hardest. It’s when Kimberly Calderon’s panic ignites like a bundle of sparklers in her stomach.

She struggles to distinguish her fear from reality.

On the night of Nov. 12, Calderon and her boyfriend, William King, went to California Pizza Kitchen at The Park. She sat facing the front door. Meanwhile, the nearby crowd from the Rock ’n’ Roll Marathon packed the Strip.

“They’re just fish in a barrel,” she thought. “They could all die.”

Another time, while the couple slept, Calderon saw King in a vivid dream, falling backward off a bridge. She woke and grabbed a fistful of his shirt.

Just nights after King was shot before her eyes at the Route 91 Harvest festival on Oct. 1, the power went out in their home. She dialed 911.

“I think they’re going to come and kill me,” she told the operator.

The woman on the other end cried.

“Were you there?” the operator asked.

New normal

It’s been three months since the bullet missed his heart by half a centimeter.

That night, when the gunshots cracked and cut through the sky, King immediately pushed himself against Calderon. She felt him jolt as she watched the bullet go into his back, a spray of blood droplets sprinkling her face.

He was taken to Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center — the hospital where he was born 39 years ago.

As the doctors wheeled away her boyfriend of more than three years, Calderon, 26, nervously pulled on her hair and watched the bodies arrive.

King was saved. Now the Summerlin couple has found a new normal and a new appreciation for every day. Like many other Oct. 1 survivors, that night continues to shape their life together, their sense of safety and their daily responsibilities.

“Everything after Oct. 1 is a first again,” King says.

On a recent weekday, it’s morning in the King home. A square of sunlight peeks through the blinds, splashing into the peach-colored house.

Calderon is catching up on sleep upstairs. Downstairs, King makes waffles.

The couple met in November 2014, when Calderon was working as a paralegal in the same office as King’s dad.

She had long, black hair and a smile that reached her high cheekbones; his bushy beard clung to his face like moss on rock.

Each had been married before. They moved in together in March 2015 but never committed their relationship to paper.

“We’re more than married,” King says now. “We’re bonded by blood.”

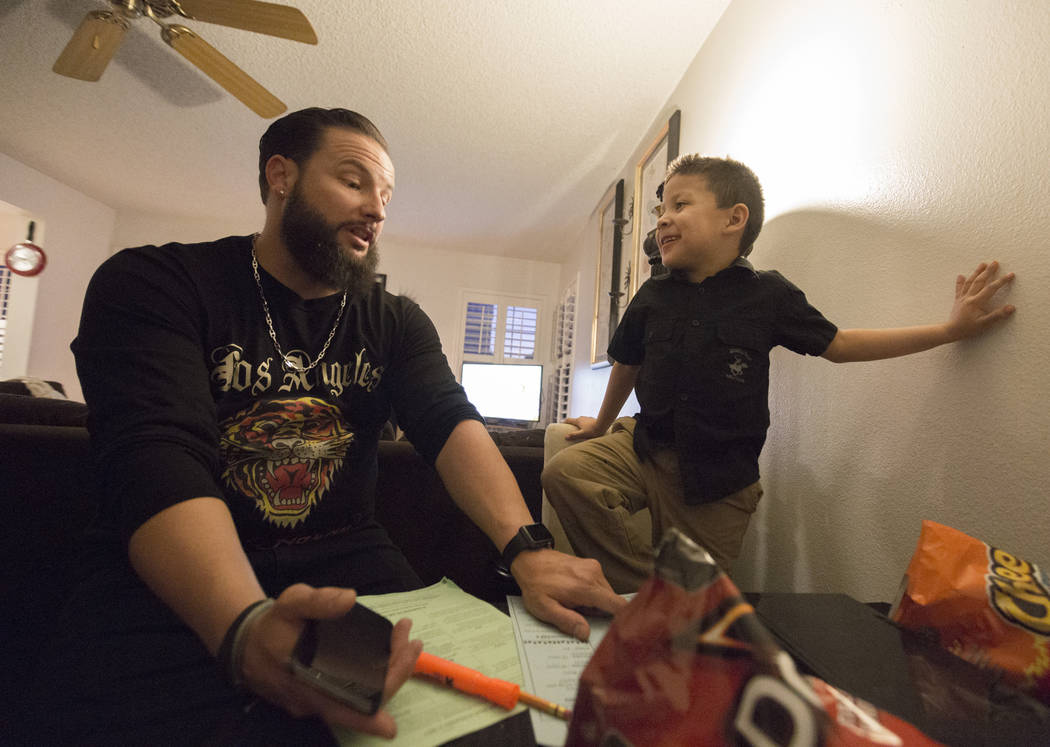

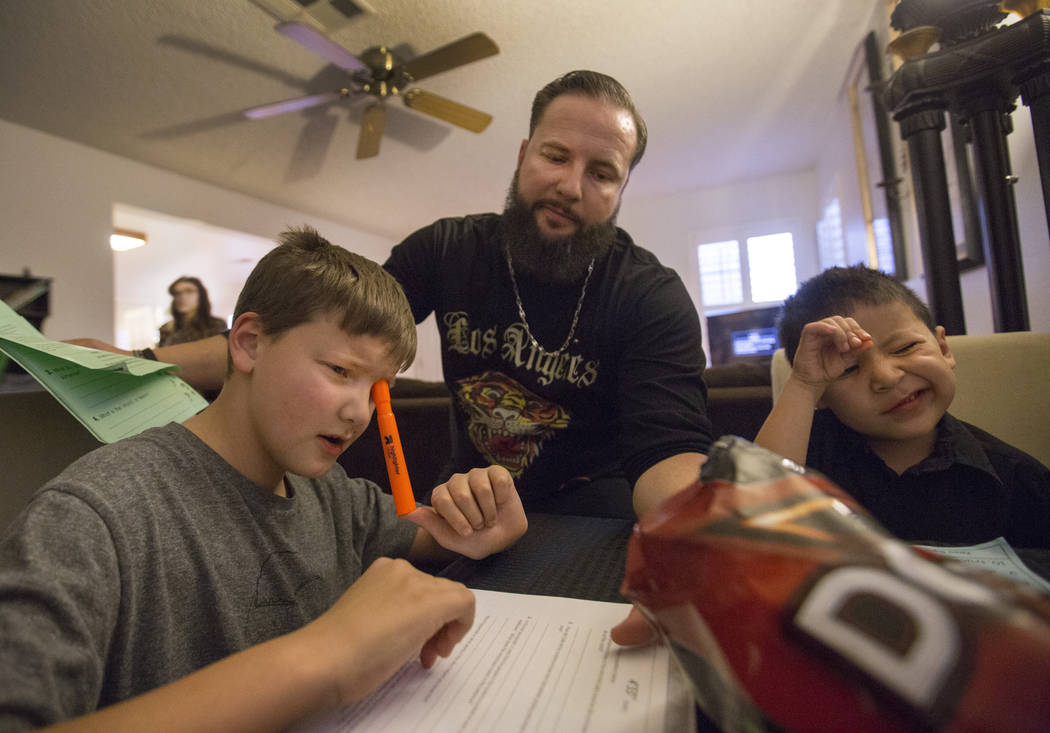

They each have two kids of their own. Max, 6, and Velonee, 8, are Calderon’s kids. Enoch, 9, and Eli, 8, are King’s boys. They wait at the table as King finishes breakfast.

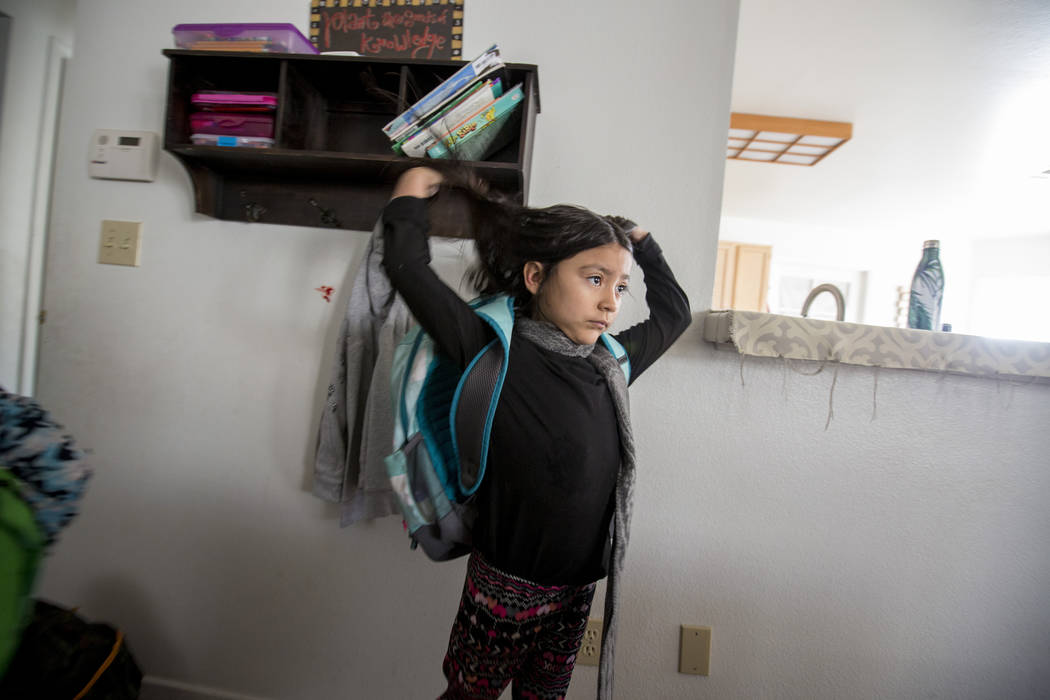

As the syrup drips off the kids’ waffles, King brushes through every last knot in Velonee’s long, dark chocolate strands, matted from a recent shower. It’s nice to take care of a daughter, he thinks.

Before they leave for school, King opens the tribal shirt folded on the table. It was torn off him Oct. 1 — and now is stained with two large patches of blood.

Wrapped in the shirt is a piece of the purple Route 91 Harvest wristband and a leather trinket.

He stows them in a drawer.

Pain tolerance

On a recent weekday, King goes to his fourth doctor’s appointment since the shooting. Edward Victoria, King’s physician, sits on a blue swivel chair and asks King how he’s doing. Calderon sits in the corner, listening.

“I tried to test it,” King tells Victoria. He means his tolerance for pain.

Pushups left him cringing, King says.

“It feels like something moving in my chest,” he says. “The bullet fragments within me.”

The doctor places the stethoscope on King’s chest. King breathes in and out.

“Your breathing here is good,” he says, easing King’s worries. “I’m not concerned about the heart.”

King’s wounds have kept him from his job as a bellman at the Delano Las Vegas, next to Mandalay Bay. For more than 18 years, he worked for MGM Resorts International, starting at the Monte Carlo in 1999. He can return to work in February. But he’s not sure if he wants to.

As he recovers, he receives $138 a week in disability. He also started working full-time with Calderon, who had been selling life insurance with Primerica. He enjoys the extra time with his kids. Since Oct. 1, the couple has hired three shooting survivors.

They are still waiting to see whether his mounting bills will be covered by the Las Vegas Victims’ Fund.

King says his hospital stay alone left him with a $31,000 bill.

Before they leave the doctor’s office, King wants to know one more thing: Can he get his vasectomy reversed?

“You want to have more kids now after this thing?” the physician asks.

“We just don’t want the time to keep going by,” Calderon says.

Permanent marks

Every so often, King is overwhelmed with emotion. Sometimes, it’s when he drops the kids off at school. Other times, it’s when he looks in the mirror and sees the smooth, reddened patch of scar tissue the size of a thumbtack on his chest.

It brings him back to the carnage — the bloodied scene of cowboy hats, boots and bodies. The injured and the dead.

He knows it’ll be with him forever.

Before the shooting, Calderon was against guns. But in the midst of the panic and the constant pangs of fire, she never wanted a gun more than on Oct. 1.

“If he can have a gun, then I want one, too,” she says.

When the couple came home from the hospital, Calderon’s son, Max, felt safer at his dad’s home. At his mom’s, the dimpled boy cried whenever she left the house. When Calderon double-checked the locks on the door and armed the house, he grew more scared she might not return.

His sister, Velonee, took it better.

“I’m happy you’re OK,” the long-haired little girl says.

King’s sons, Enoch and Eli, were concerned but also curious. They wanted to see the bullet wound.

A healing reunion

Shortly after he was shot, King says, he was rescued by a former Marine. The man and his wife threw their bodies in front of a moving car to get Calderon and King to the hospital.

The man, Joseph Nolan, 26, had pressed hard on King’s chest, sticking his finger in the bullet hole to stanch the bleeding. Nolan and his wife, 25-year-old Paola, came to the concert from Los Angeles. They had been married just two months.

Ever since King got out of the hospital, he knew he wanted to reunite with the couple. They met again in Las Vegas on Dec. 9.

That morning, King and Calderon threw up because of nervousness.

“I feel like I’m meeting the president,” she says.

King spots them coming down the escalator. He can’t keep his brown eyes dry. Calderon’s dark eyelashes brim heavy with tears.

Nolan flashes a boyish smile.

“How you doin’, sir?” he asks.

Later, they take the couple to the Las Vegas Community Healing Garden. They pass each of the 58 trees, one for each life lost. They gaze at the angels in the trees, the butterflies in the branches, the letters written for “Mom.”

In the center of the garden, sprouting out of a heart-shaped mosaic, is the Tree of Life, illuminated by white lights. The couples talk about their progress.

“The only reason we didn’t get shot was chance,” Paola says.

Joseph looks at the names on the memorial wall, the cowboy boots filled with flowers. “That person was here two months ago,” he says.

Earlier that night, a woman at the garden sang a song she wrote for the city.

We are reunited. Yes, we’re Vegas Strong.

We went from strangers to family.

Forever changing our destiny.

We have a second chance at life.

‘So blessed’

That night, the two couples eat dinner at Rivea, on the 64th floor of the Delano Las Vegas.

They stand outside, on the balcony overlooking Las Vegas Village, the Route 91 Harvest festival site. Glowing lights blanket the Strip. The Luxor pyramid blinks. The High Roller flashes blue in the distance.

“It felt like it was the end of the world,” Calderon says of Oct. 1.

Joseph Nolan remembers the sound of bodies being hit by bullets: hollow, like a cow hit by a baseball.

“Helping you gave us something to focus on with everything going on,” he tells King.

They think about how a month ago, none of them would have been able to sit there, overlooking the Strip from a similar vantage point as the shooter.

Seeing the empty lot, though, gives them some comfort.

“We’re so blessed. I look at it as a chapter being open, and a future that we’re going to have,” King says.

Lowering his voice, he turns to Calderon. His ears turn red. He gets on one knee.

“That night, it’s where we became one,” he says.

He pulls out the homemade leather ring, made from his tattered shirt and purple wristband. He hopes he can squeeze it on Calderon’s ring finger.

“Will you marry me?”

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @brianarerick on Twitter.

Related

Las Vegas friends find strength in one another after shooting

Therapy helps Las Vegas shooting survivor with panic attacks

Las Vegas woman survives shooting, struggles with emotional scars

Las Vegas shooting survivor finds courage to race again

Identical twins, hurt in Las Vegas shooting, hope to help others