Mixup warned ambulances to avoid UMC after Las Vegas shooting

A Clark County dispatcher told emergency responders that University Medical Center was “completely out of beds” late Oct. 1 even though the hospital had plenty of capacity to help victims of the Strip mass shooting, records obtained by the Las Vegas Review-Journal show.

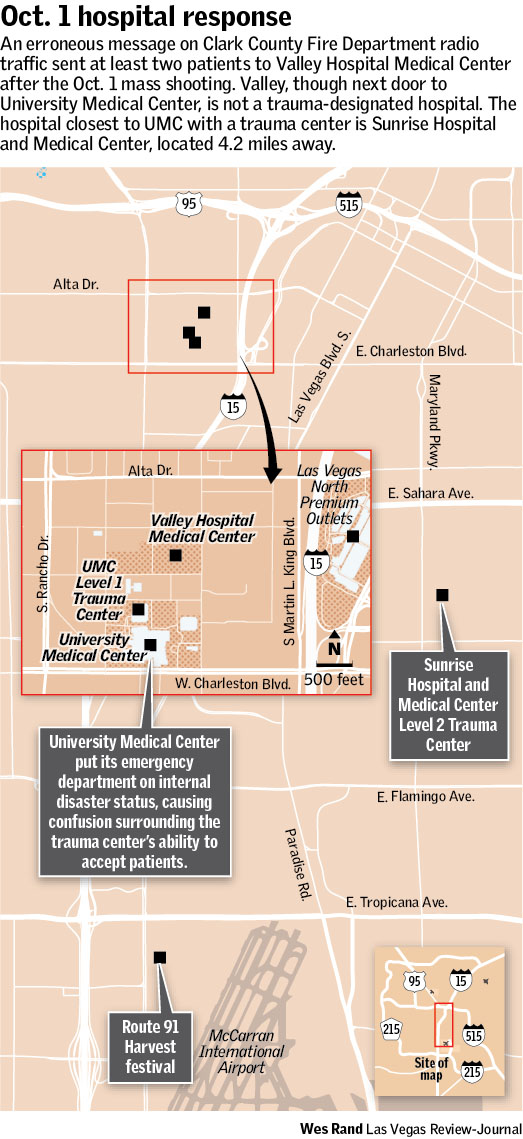

It took at least 15 minutes for the erroneous message to be corrected, but the ensuing confusion lasted past midnight, and at least two people were diverted to a hospital less-equipped to deal with traumatic injuries.

The error is the most significant known lapse in that night’s execution of the emergency plan that local first responders learn through extensive training.

The mix-up occurred after the hospital issued an “internal disaster” alert, meant to forewarn staff to an influx of patients and a potential shortage of supplies and staff, UMC spokeswoman Danita Cohen said. She declined to elaborate, and hospital officials said staff took no action to divert patients to other hospitals.

County officials cannot explain how the miscommunication occurred, but said they have no plans to investigate.

“Be advised UMC is completely out of beds,” a dispatcher told county Fire Department personnel at 11:10 p.m., about 55 minutes after the final burst of gunfire rained down on Route 91 Harvest festival concertgoers. “I know you need to go where you need to go, but just be advised.”

Any Las Vegas Fire Department, Henderson Fire Department or North Las Vegas Fire Department responders tuned to the county channel also would have heard the message.

A miscommunication

Clark County Fire Chief Greg Cassell said the message was a miscommunication, and that someone — either a hospital staffer or a Fire Department employee — misconstrued the alert. Hospital and county fire officials say that UMC’s trauma center, which is separate from the emergency department, never closes its doors. In fact, UMC officials say, the doors to their trauma unit were literally wide open that night to respond to the event that left 58 people dead and hundreds more injured.

County protocol states that a hospital on internal disaster should be bypassed in all cases except for patients in cardiac arrest or those who can’t be ventilated. Cassell said that under an internal disaster declaration, first responders would avoid the UMC emergency department but not the hospital’s Level 1 trauma center.

A security perimeter established by Metropolitan Police Department officers around the UMC campus also created confusion that night for both ambulances and civilians.

The Review-Journal has learned of two patients — one in an ambulance, another in a truck — who were diverted to Valley Hospital Medical Center, which is next door to UMC but does not have a trauma designation.

It is not clear whether any other ambulances were diverted to other hospitals as a result of the erroneous message.

It wasn’t until about 11:25 p.m. that a correction was broadcast. “We’re at UMC Trauma. They’ve been giving us information that they have plenty of beds open,” an emergency responder said. “They want as many patients coming to Trauma as possible.”

At 11:31, another responder repeated the message, “We’re at Trauma. They want as many patients delivered to Trauma as you guys can send here.”

But later phone calls between county fire staff and UMC, which is operated by the county, indicate the confusion persisted into the early hours of Oct. 2.

‘The fog of war’

Cassell said the mistake could have resulted from the intensity of the event, the worst mass shooting in modern U.S. history.

“We can’t narrow it down to who exactly said what, we just assume during the fog of war, it was misconstrued and miscommunicated,” Cassell said, adding that the department does not plan to further investigate.

Clark County Commission Chairman Steve Sisolak and Commissioners Susan Brager and Larry Brown said they were unaware of the problem until they were asked about it by a Review-Journal reporter last week. Sisolak said he trusted Cassell’s judgment.

UMC is the only Clark County hospital with a Level 1 trauma center — a rating that indicates a hospital is equipped to handle all injuries, including gunshot wounds.

The trauma center nearest to UMC, at Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center, has a Level 2 designation, meaning it lacks certain specialist care available at UMC. Sunrise is listed under county protocol as an acceptable destination for penetrative injuries, but it is 4.2 miles from UMC — about a 15-minute drive with no traffic.

Click image to enlarge

UMC officials vehemently deny that hospital staff took any action to turn away incoming patients Oct. 1, insisting that the emergency room and top-rated trauma unit quickly ramped up for the expected flood of wounded.

“At no point was a patient deterred from seeking care,” said Mason VanHouweling, UMC’s chief executive officer.

Officials have held up the planning and training that occurred beforehand as exemplary.

At a Nevada Homeland Security Commission meeting two months after the tragedy, Caleb Cage, chief of the state’s Division of Emergency Management, called the response the night of the shooting “textbook.”

Mass casualty guide

The “textbook” for mass casualty events is included in a 174-page document titled “Clark County EMS System Emergency Medical Care Protocols.”

The guide, which covers a wide range of medical situations, includes more than three pages dedicated to instructing emergency responders on patient transport based on the severity of injuries. It says a hospital that declares an internal disaster should be avoided.

“If a hospital declares an Internal Disaster, that facility is to be bypassed for ALL patients except patients in cardiac arrest, or in whom the ability to adequately ventilate has not been established,” the protocols read.

County Fire Emergency Medical Services Coordinator Pat Foley said a misunderstanding of terminology likely contributed to the confusion. In addition to its internal disaster declaration, the hospital was on lockdown.

“When we hear a word like ‘lockdown,’ that’s different than ‘divert,’ that’s different than ‘internal disaster,’ and it’s easy to mix the three up or hear another verbiage and go, ‘Oh, that’s what they’re talking about,’” Foley said.

The lockdown required Metro officers to set up a perimeter around the hospital. That’s standard procedure for hospitals during an active shooter situation to protect patients and staff from any threat, said VanHouweling, UMC’s CEO.

That shouldn’t have prohibited emergency or civilian vehicles from entering the premises, he said.

The dispatch log and one firsthand account, however, indicate that occurred.

At 11:24 p.m., an emergency responder said over county fire radio traffic, “We’ve been diverted from Trauma to Valley. We’ll be at Valley Hospital.”

Cassell noted that the message itself doesn’t mean the responder thought the hospital was shut down.

“Most likely the patients they had were not emergent (or) critical and not in need of the higher level of care provided at UMC Trauma,” he said. “This in no way says UMC Trauma was closed.”

Turned away

The account provided by Las Vegas police Detective Richard Golgart, who was off duty and attending the concert with his daughter, is more definitive.

He said he made it to UMC with a truckload of wounded victims shortly after the shooting. But later, when he tried to return with his daughter, Rylie, who had been shot in the back, officers outside UMC turned him around, he said.

“As I was trying to turn to UMC, they stopped traffic around UMC and were diverting everybody at that point” to different hospitals, Golgart said. Two Metro officers working at the intersection of Shadow Lane and Goldring Avenue directed him to Valley Hospital Medical Center next door, where Rylie was stabilized and had surgery.

Metro spokesman Aden OcampoGomez said he could not confirm that officers turned anyone away from UMC. If that happened, he said, it would be contrary to department policy.

“We can’t turn people away from medical,” he said. “We’re not doctors.”

OcampoGomez said the incident, if it occurred, was not significant.

“Both hospitals are not that far away, so they’re not turning them away to a far-distance hospital where something tragic would happen,” OcampoGomez said.

There is a difference, however. Valley Hospital does not have a trauma center. It has only an emergency department equipped to handle strokes, heart attacks, broken bones and other injuries. The hospital called in surgeons that night, but it typically does not staff its operating room around the clock and generally transfers gunshot victims to trauma centers.

Kay Godby, a UMC nurse and the hospital’s clinical coordinator of readiness response and compliance, was at the county’s Multi-Agency Coordination Center and Medical Surge Area Command, located at Fire Station 18 on Flamingo Road, east of the Strip, during the response.

In the early hours of Oct. 2 — long after the 11:31 p.m. dispatch correction about UMC’s status — Godby received a call from the county Fire Department asking whether UMC had shut down.

“They (county fire) asked me to call incident command (at UMC) to find out if we were closed, and I talked to the incident command and she verified we were not closed,” Godby recalled.

Vick Gill, associate administrator for UMC, who was at Las Vegas police headquarters performing duties similar to Godby’s, said he never received any indication that the hospital was full or diverting patients.

“I remember vividly letting them (county officials) know they could send patients to UMC,” Gill said.

Disappointment and frustration

For UMC Chief of Trauma Dr. John Fildes and trauma nurse Toni Mullan, the confusion over UMC’s status that night is frustrating.

“I wanted more victims, because we were so ready, I just wanted, I felt, we knew they were out there,” Mullan said.

A corridor linking the hospital’s trauma building and emergency department was lined with empty gurneys in the minutes after news of the shooting spread. Staff were ready, rolling beds “like a PEZ dispenser” out the trauma center’s doors, Fildes remembered.

Despite the miscommunication, patients soon arrived in waves. Mullan recalled that all areas designated to handle patients grew crowded, but UMC never ran out of space.

“Dr. Fildes and I, at one point, were sitting on a gurney waiting for more patients,” Mullan said.

Cassell said the Fire Department did not launch an investigation into how the miscommunication occurred, nor does he plan to.

“There’s nothing to look into,” he said. “It was a short miscommunication apparently, and it was quickly corrected.”

But 323 first responders who were deployed that night by private ambulance company American Medical Response are being interviewed to determine whether any were turned away at UMC, said Damon Schilling, the company’s government and community affairs manager.

“Because there’s so much curiosity about it, it caused us to be curious,” Schilling said. “Even if it did happen, it wouldn’t have even mattered because we wouldn’t have allowed them to tell us that.”

Brown, the county commissioner, said he trusted Cassell’s judgment.

“If Chief Cassell felt that there’s not a need for an official investigation, I’m very comfortable with that. He runs one of the best departments in the country,” Brown said. “If that breakdown happened, I’m sure it’s been addressed.”

‘Every second matters’

But Brager, the commissioner and member of the UMC board of trustees, concluded otherwise.

“Every minute when you’re bleeding to death matters, every second matters,” she said.

Indeed, 14 shooting victims died that night after making it to hospitals alive, Dr. Clarence Dunagan said Friday at the first Southwest Regional Emergency Medicine Conference at MountainView Hospital.

It is not clear whether any of those victims were turned away from UMC or went elsewhere as a result of the county’s dispatch error.

Brager said she wants the Fire Department to have a policy in place to verify whether a hospital reaches capacity when a mass casualty incident occurs.

Still, she said the miscommunication did not affect her high regard for the emergency response on Oct 1.

“I think from our first responders to members of the public went above and beyond what seemed humanly possible to take care of the injured.”

Contact Jessie Bekker at jbekker@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4563. Follow @jessiebekks on Twitter. Review-Journal staff writer Michael Scott Davidson contributed to this report.