Nevada Supreme Court ruling could expose MGM Resorts in Las Vegas shooting

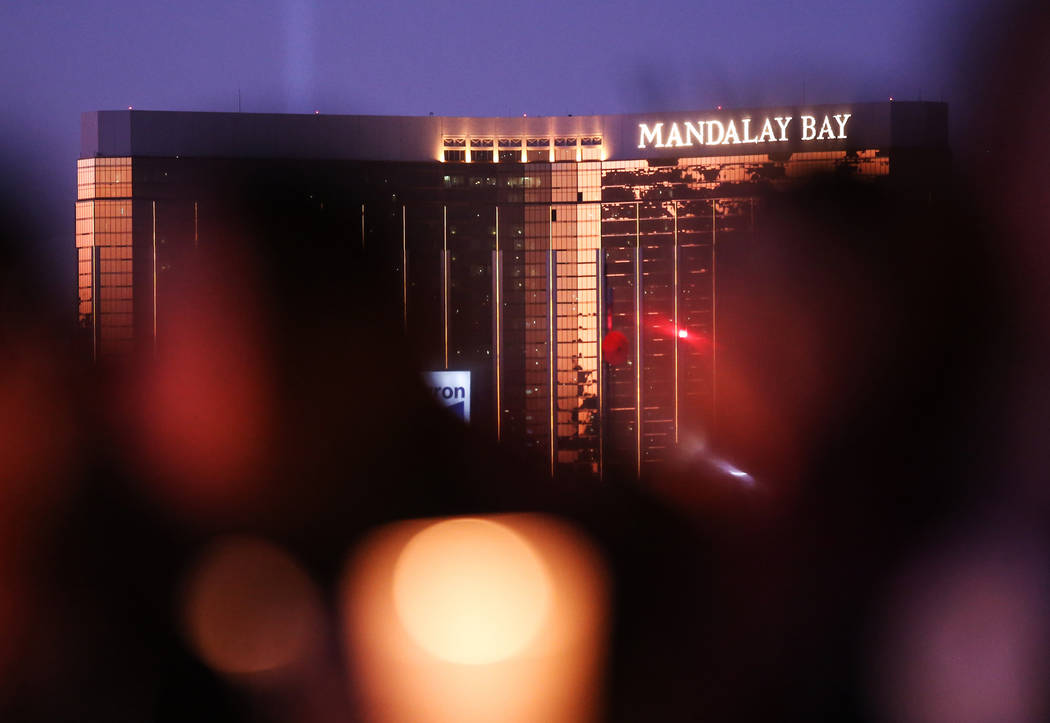

Just days after the Oct. 1 shooting, a Nevada Supreme Court panel issued a decision that could sharpen questions about the adequacy of security at Mandalay Bay and increase its liability.

The ruling is hovering over the hotel-casino and its owner, MGM Resorts International, as the company braces for a run of lawsuits related to the shooting and an expensive, yearslong court battle. A shooter killed 58 concertgoers and injured more than 500 others at the Route 91 Harvest music festival across the street from his 32nd-floor Mandalay Bay suite before apparently taking his own life.

The Supreme Court case stemmed from an assault in 2010 on a California couple, Carey Humphries and Lorenzo Rocha, inside the New York-New York, another MGM property. A lower court dismissed their lawsuit on the grounds the resort had no knowledge the attack would occur.

But in a 2-1 decision, the Supreme Court panel overturned that order. It ruled that the New York-New York should have known the attack was foreseeable because there had been similar incidents of violence there. Humphries and Rocha were attacked by a man at the casino, and she suffered a fractured skull. Evidence in the case showed there were three fights a week at the resort.

Justices James Hardesty and Ron Parraguirre were in the majority, and Justice Kristina Pickering dissented.

Craig Drummond, one of the lawyers who appealed to the high court on behalf of the couple, said the decision provides “pretty clear guidance” on cases of violence at hotel-casinos, including the Strip shooting.

“You no longer have to show the exact circumstance was foreseeable,” he said. “I think it makes it difficult for MGM Resorts to get the Mandalay Bay case dismissed by arguing it’s a lone shooter and they couldn’t have ever foreseen that.”

Longtime civil litigator Robert Eglet said the decision opens the door for plaintiffs to question whether MGM Resorts had sufficient security measures to protect its casino guests and those at the Las Vegas Village concert site, which the company also owns.

Those questions have surfaced in the most recent round of lawsuits.

The Humphries decision also could be interpreted to include similar incidents of mass violence at venues other than Mandalay Bay, said Eglet, who is preparing to sue MGM Resorts on behalf of victims of the shooting.

“I think it broadens the scope of the things a judge has to look at to determine whether this event was foreseeable,” Eglet said. “In other words, it’s no longer, ‘Has anything like this ever happened at Mandalay Bay?’ It’s, ‘Has anything happened like this anywhere?’”

But Jean Sternlight, director of the Saltman Center for Conflict Resolution at UNLV’s Boyd School of Law, said Mandalay Bay still has a strong defense under state law.

The company’s lawyers likely will argue that it was unforeseeable that a guest would bring a large number of high-powered rifles into the resort and shoot at a concert across the street, Sternlight said.

“I think the victims will have a challenging time trying to prove that Mandalay Bay failed to exercise due care in protecting the concertgoers,” she said.

MGM Resorts lawyers filed court papers this month asking the entire Supreme Court to review the panel’s decision on the Humphries case, arguing it has “significant implications beyond just these litigants.”

The lawyers contended the 11-page opinion “eviscerates”a state law that protects businesses.

Reversing the panel’s decision could spur criticism that the court is trying to protect the powerful casino industry, Eglet said.

“I don’t think it would pass the smell test,” said Eglet, a former Nevada Trial Lawyers Association president who has won several large jury verdicts in recent years.

Tragedy after tragedy

The massive litigation compares to another tragedy that cost MGM a large legal settlement: the infamous fire at the old MGM Grand, which killed 87 people and injured more than 700.

On Nov. 21, 1980, a smoldering electrical fire broke through a wall in the first-floor deli, creating a giant fireball that swept through the hotel-casino, blowing out the front doors and leaving behind death and destruction.

The wall of fire was fueled by flammable plastic furnishings, fixtures and wall coverings. There were no sprinklers in place to dampen the intense flames.

Some died trying to beat the fast-moving blaze out the casino entrance, but most fell victim to smoke inhalation and carbon monoxide poisoning in the 25 floors above the casino as a stream of thick black smoke traveled up through elevator shafts, air ducts and other openings.

Litigation over the fire was hard-fought and lasted years. It never went to trial.

For its share of the settlement, MGM had paid more than $100 million by 1983, which would amount to about $260 million in today’s dollars. Several years later, the company rebuilt and sold the MGM Grand to Bally’s Corp., which rebranded the property on Flamingo Road and Las Vegas Boulevard.

MGM went on to become the largest employer and one of most politically influential businesses in the state, with 13 hotel-casinos on the Strip, including a new MGM Grand on Tropicana Avenue.

Like the Strip shooting, most of the fire victims were tourists. Lawsuits were filed across the country, and eventually the cases were consolidated in federal court in Las Vegas. There were more than 1,000 plaintiffs and more than 100 defendants.

Some legal experts described it as the largest mass disaster litigation of its time.

Consolidation expected

Lawyers expect the shooting lawsuits to be consolidated, as well, once they are all filed. There is a two-year statute of limitations.

Eglet believes the shooting has had a greater impact on the community than the MGM Grand fire.

“This wasn’t just an accidental fire because of negligence or product defect that hurt a lot of people,” said Eglet, who expects to be at the center of the high-profile case in the months ahead. “This was a direct attack on our city. And so I think everybody collectively feels that anxiousness, that anxiety and that distress over this happening to us.”

But Steve Morris, who defended MGM in the fire case, said it may still be more difficult for victims to blame the company in the mass shooting case.

“Here you have an abhorrent actor who just happened to be in the hotel,” Morris said. “The guy took a hammer, knocked the windows out and started shooting people. It’s not an act by the hotel.”

Veteran lawyer Will Kemp, a key player on the plaintiffs’ side in the fire litigation, said that argument can’t be ignored.

“They’ve got the shooter committing an intentional act that they can argue was not foreseeable,” he said.

Eglet plans to join forces with lawyers across the country in a barrage of lawsuits over the shooting. Investigators hired by Eglet are digging up evidence, even as Las Vegas police have yet to complete their own criminal investigation.

Questions ahead

As big as the fire litigation was, there is potential for many more victims to sue over the shooting, Eglet said.

There were only 5,000 people staying at the MGM Grand in 1980, but more than 20,000 attended the Route 91 Harvest music festival.

Many of those people are suffering from stress, Eglet said.

“Look, there are people right now who can’t sleep, who are having nightmares, and it’s playing over and over in their head and they’re having all kinds of problems,” he said. “They can’t work. They can’t function properly. I mean, this was turned into a battlefield.”

Added to those complaints will be the cases of the people killed at the festival and the survivors who were shot or trampled while fleeing the hail of gunfire, Eglet said.

Kemp said filing a case in California might be more favorable to a plaintiff, because MGM Resorts is not as well-known there.

“They give a lot of money to judges and politicians in Nevada, like most big employers do,” said Kemp, who does not plan to be involved in the legal fight. “So they have a lot of influence here in the state.”

“It’s not so much that you’re worried about them paying off a judge or a judge being biased. It’s more like you’re in their hometown. They’re going to get the close calls.”

High-profile personal injury lawyer Ed Bernstein shares Kemp’s concerns about the company’s potential influence.

“When the MGM fire occurred, the MGM did not have the same kind of reach that it has now,” said Bernstein, who is considering lawsuits against the company.

So far, fewer than two dozen lawsuits have been filed in Las Vegas and California over the shooting. Fourteen victims, mostly alleging they suffered stress during the massacre, filed cases in the Clark County District Court on Wednesday.

Eglet said he is encouraging lawyers across the country to wait.

“I think that the community has to have time to heal,” he said. “We need to do our due diligence before we start filing all of these lawsuits. We need to let Metro finish their investigation and let the FBI finish their investigation.”

Eglet said he wants to make sure that he is suing the appropriate defendants.

But the scrutiny eventually will come.

There will be hundreds of depositions and hundreds of thousands of pages of court filings seeking company records about its security procedures, staffing levels and management history, lawyers said.

And the company will face the same questions testing its liability over and over again in court. Much of the case could turn on how the shooter turned his room into a sniper’s nest with an arsenal of weapons without being detected.

At the concert site, many questions center on whether there were enough exits and security officers on hand and whether there was an emergency evacuation plan, Eglet and Kemp said.

Once the shooting started, there was no direction from security officers telling people what to do or where to go, Eglet said.

“It was pandemonium, just a free-for-all,” he said.

The questions continue to grow as police and MGM Resorts officials remain quiet about key facts surrounding the massacre.

“There’s going to be a vast amount of discovery done in this case to figure out exactly what happened and what went wrong,” Eglet said.

Valet parking attendants, bellmen, housekeepers, security officers, front desk clerks, casino hosts and executives all will be among those questioned under oath, lawyers said.

MGM Resorts would not comment on the litigation.

In a statement, the company said: “The tragic incident that took place on October 1st was a meticulously planned, evil senseless act. Out of respect for the victims we are not going to try this case in the public domain and we will give our response through the appropriate legal channels.”

Eglet said he was confident that the litigation will bring out the truth.

Added Kemp: “Oh yeah, you will find the truth. Fifty-eight people dead, more than 500 injured. Yeah, the truth will come out.”

Contact Jeff German at jgerman@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4564. Follow @JGermanRJ on Twitter.

Answers sought

MGM Resorts International could face repeated questions in court about hotel security:

— Did Mandalay Bay employees unwittingly assist the shooter's deadly mission by not detecting the many high-powered weapons he brought to his suite?

— Were employees properly trained to raise suspicions about the "Do Not Disturb" sign left on his door for days?

— Did Mandalay Bay have enough security on hand the night of the shooting and an emergency plan to deal with it?

— Who was watching video surveillance cameras?

— Were there enough cameras?

— Were Mandalay Bay security officers armed?

— Why did the timeline for when Mandalay Bay security officer Jesus Campos was shot change so many times?

— Did anyone hear the shooter breaking the windows in his 32nd-floor suite before he opened fire?

— How was the shooter able to leave his own video surveillance cameras on a food service cart without anyone discovering them before the shooting?

Related

RJ reporters discuss shooting lawsuits, shooter's Mesquite home — VIDEO

14 more lawsuits filed over mass shooting in Las Vegas

Father of Las Vegas shooting victim files wrongful death lawsuit

Lawyers seek order requiring MGM Resorts to preserve evidence