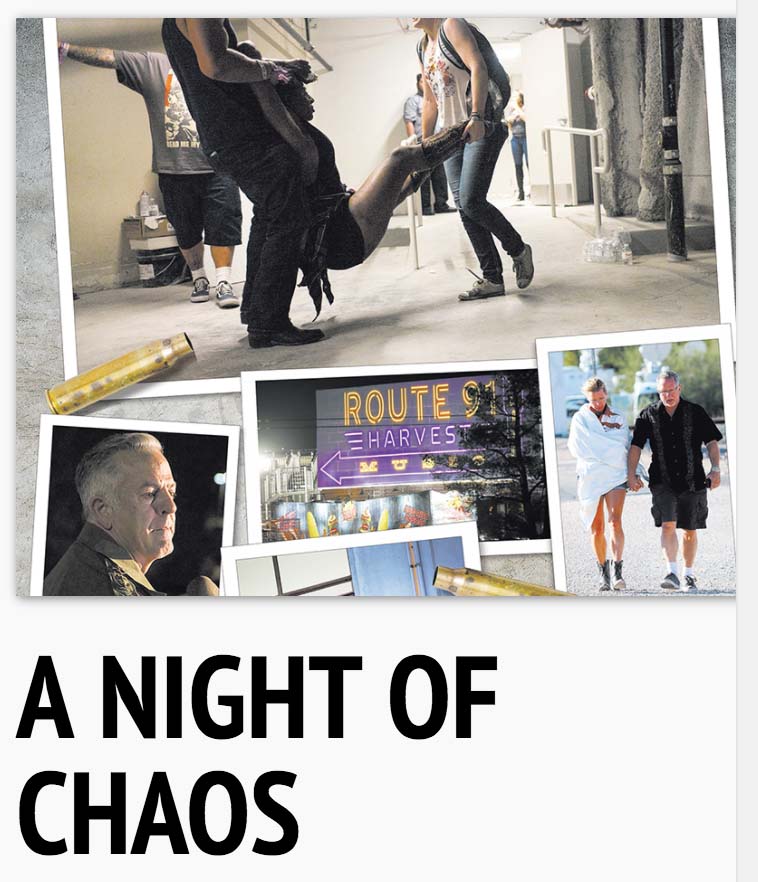

Survivors recount ‘sheer panic’ during Las Vegas shooting

There was no theater or nightclub for police to surround, no school or office building to lock down.

The attack on Las Vegas unfolded in the open, and there was nothing to contain the panic and confusion.

The shooting itself lasted less than 15 minutes. The ensuing chaos stretched on for hours, swallowing the Strip and the valley beyond.

Resorts 3 miles from the scene went on lockdown. McCarran International Airport suspended flight operations. Authorities blocked traffic on two of the state’s busiest stretches of road.

The Oct. 1 attack on the Route 91 Harvest country music festival left 58 people dead and wounded an additional 546. (The gunman died in an apparent suicide.) It also sent thousands of terrified concertgoers fleeing in all directions, triggering phantom reports of additional shootings at other locations.

Unsure where the shots were coming from or where to find safety, people sheltered in neighboring resorts and businesses, hid behind bushes and cars, or ran through vacant lots, down backstreets and onto airport runways.

Ambulances were kept at a distance until police were certain the attack was over, leaving some concertgoers to load the wounded into whatever vehicles they could find and speed away to seek help.

The chaos soon spread to valley hospitals, where emergency rooms filled with gunshot victims and waiting rooms overflowed with frantic loved ones.

Others — displaced from their hotel rooms and, in some cases, separated from friends and family members — spent the hours after the attack in emergency shelters set up in Strip showrooms or the Thomas & Mack Center.

Even in a nation all too familiar with mass shootings, this was an attack like none other.

Unbounded by walls, locked doors or a ceiling, the terrible event rippled unchecked through Las Vegas, sweeping up tens of thousands of residents and visitors, many of them far outside the range of the gunman’s bullets.

One month later, here are some of their stories.

‘They ran to a safe place’

Maria Mackert was nearing the end of an eight-hour shift when she stepped outside Allegiant Air’s maintenance hangar at about 10:20 p.m. for a quick cigarette break.

A shirtless man and two women ran toward the airplane mechanic, pleading for help. All speaking at once, the group explained how they scaled the towering security fence surrounding McCarran International Airport to escape gunfire.

“At first I thought they may be exaggerating due to drugs or alcohol, because that’s what people do in Vegas,” Mackert said.

She told them to take cover in the garage as she stepped back outside to call the police.

Allegiant Air employee Maria Mackert, a mechanic, sits inside Allegiant Air’s maintenance facility at McCarran International Airport in Las Vegas, Monday, Oct. 23, 2017. Joel Angel Juarez Las Vegas Review-Journal @jajuarezphoto

Then the swarm came.

About 300 people fleeing the shooting breached the airport’s security fence, ran onto the tarmac and eventually brought takeoffs and landings to a halt for more than two hours, forcing the diversion of 25 flights into Las Vegas.

Some people scaled the fence. Others crawled through holes punctured in the barrier. The razor wire atop the fence ripped their clothing and left some of them with minor abrasions.

About 35 of them ran about a half-mile east across the airfield to Allegiant’s 18,000-square-foot maintenance base, a last remnant of the extinct Terminal 2.

“People were crying and freaking out,” Mackert said. “I just kept trying to tell them that they ran to a safe place. They really did not know the danger they were in while running from danger.”

One man repeatedly plunked coins into the break-room vending machine to buy chips and snacks. Pretzels usually saved for airline passengers were handed out along with bottled water, soda and juice.

People with ripped clothes draped themselves with blankets. Employees shared cellphone chargers and computers with those wanting to send messages to concerned family members. Others cried while recounting what they saw and heard.

“There were people who just wanted a sympathetic ear, and they just wanted somebody to listen,” Mackert said. “That’s what I tried to do.”

— Art Marroquin

‘It was sheer panic, basically’

Ian and Wendy Gomm had come to Las Vegas from Sheffield, England, for 10 days of vacation.

They visited Fremont Street, ate good food and, on Oct. 1, hung around the pool at the Luxor, where they stayed.

Ian Gomm, 52, said he wasn’t familiar with the Route 91 Harvest festival, but other guests at the pool were clearly excited about it. They played country music and sang and danced along.

At about 9 p.m., the Gomms visited the Skyfall Lounge on the 64th floor of the Delano, where they took photos and video of the Strip.

They didn’t know anything was wrong until after they took the elevator to the ground floor.

They saw a crowd of people running, shouting and screaming about a gunman. Ian Gomm heard banging. He and his wife ran with the group.

“It was sheer panic, basically,” he said. “You didn’t know whether you were doing the right thing. You didn’t know whether to run or stay.”

They made it back to the Luxor at around 11:15 p.m. They turned on the TV to watch the news. About an hour later, a voice came over a speaker in their room to announce that the hotel was on lockdown.

That Monday, the Strip was somber. Ian Gomm felt upset walking around. They left for England the next day as scheduled.

Back in England, he said he absolutely will return to Las Vegas someday.

“You can’t live your life worried,” he said. “I won’t be put off by anything.”

— Wade Tyler Millward

‘Out-of-their-mind scared’

Judith Schulz was working a cash register at the Rebel gas station on Tropicana Avenue and Koval Lane where she is an assistant manager. First, she heard the shots. Then she saw the wave of people.

Judith Shulz was working a register at the Rebel gas station on Tropicana Avenue and Koval Lane on Oct. 1 when her store was swarmed with people fleeing from the Route 91 Harvest Festival. Judith Shulz

“There was just a swarm of people coming across the street,” she said. “Running, screaming, bleeding.”

She watched them run through traffic and jump the fences of the airport across the street.

“My store got bombarded with people,” she said. “They were sitting along the cooler doors, around the chips, the floor, the slot machines.”

Schulz said she had 50 or more people inside her store at one point, with dozens more in the parking lot.

“Everybody was just, like, out-of-their-mind scared.”

— Blake Apgar

‘Like walking into the apocalypse’

Entrepreneur, actor and TV personality Forbes Riley was attending a private party at the Foundation Room near the top of Mandalay Bay when the shots rang out.

The Las Vegas skyline glowed in the background as she took photos with friends. Like many, she thought the first crackle of gunfire was fireworks.

She watched the entire shooting unfold below as thousands of concertgoers fled the festival grounds in panic. Others lay still on the ground.

She checked her phone but couldn’t figure out what was going on.

Her group was ushered back inside the restaurant, and within minutes someone entered and screamed for everyone to get on the ground face down.

“I turned around, and I just see a giant machine gun,” she said.

Not knowing it was the police, she bolted back out onto the terrace to hide behind a large flowerpot. Before she could find a better hiding place, a SWAT officer yelled at her to put her hands up.

Riley wound up spending 12 hours in the Foundation Room with 50 other people. While they were locked down, they weren’t allowed to even use the restroom without an escort, she said. She was released from the restaurant at about 9:30 a.m.

“I go downstairs with my friend, and there’s nobody in the Mandalay Bay,” she said. “You know, casinos are never quiet. There was not a sound of any machine or anything.”

As she walked down the Strip barefoot with her high heels in hand, she noticed the cars were gone too. Patrol car lights were still flashing, but she didn’t hear a sound as she walked hand-in-hand with her friend.

“It was like walking into the apocalypse,” she said. “It really was.”

— Blake Apgar

‘I have to get home to my son’

Allison Gurley and her husband, Mike, spent three nights in Las Vegas to celebrate her 46th birthday on Oct. 1.

They were in their third-floor room at Mandalay Bay and learned about the shooting from Gurley’s mother in Boston, who called at around 11 p.m. after seeing it on the news.

Gurley hadn’t heard any gunfire. She kept the lights off and avoided the window. Outside she could see helicopters.

Her sister texted her reports of multiple shooters. Later, her sister informed her that the shooter was inside Mandalay Bay.

Gurley’s calls to the hotel front desk and room service went unanswered. All she got was hold music.

“In hindsight, I’m sure everyone went home or was busy helping,” she said. “What was scary was not knowing what was going on.”

To stay quiet, she kept the TV off. She checked Twitter and found tweets about a car bomb at the Luxor. She thought about the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks and the 2013 marathon bombing in Boston, where she lived at the time.

She asked her husband over and over when it would end. She worried the building would explode. They reviewed the evacuation route. Do they stay? Do they leave? Do they help?

“I have to get home to my son,” she thought.

They heard sirens. She got startled by the air conditioning turning on.

Around 3:30 a.m. Monday, officers dressed in military-grade gear burst into the room.

“My husband said later, ‘I’ve never been so happy to see a gun,’” she said.

— Wade Tyler Millward

‘Sunday nights aren’t usually like that’

Cabbie Dustin Webster had just delivered some tourists from Mandalay Bay to McCarran International Airport when the first reports of gunfire came over the radio in his taxi and the handhelds worn by the Metropolitan Police Department officers in front of Terminal 3.

Officers told him to stay away from Mandalay Bay, but he raced back there anyway to check on fellow drivers and the doormen he knows there.

The driver and supervisor for Desert Cab said he could hear the gunshots as he pulled away from the airport. He made it back to the resort just as the last two bursts sprayed down from the 32nd floor.

The scene outside the lobby was strangely calm — people smoking cigarettes and staring down at their smartphones, a doorman loading guests into a cab.

Then hotel security personnel showed up and ordered everyone to get inside the building, only to be overruled seconds later by Metro officers who said the shooter was inside and told everyone to get out.

Webster let three doormen pile into his cab and sped away from the resort, turning south on Las Vegas Boulevard.

“That’s when all the cops were just flying in from everywhere,” he said, some of them in unmarked cars racing to the scene on the wrong side of the road.

Webster stopped at a convenience store at Warm Springs and Las Vegas boulevards, where the doormen bought some beer. Then the cabdriver took the men to their homes and went back to work.

His first stop was the airport, where he picked up some tourists and delivered them to The Venetian, only to find the resort locked down and its driveway blocked by metal barriers.

“I ended up leaving them on the curb with their luggage,” Webster said. “The rest of the night ended up being super busy. Sunday nights aren’t usually like that.”

— Henry Brean

‘Something was really wrong’

Kevin Nelson, of Fort Worth, Texas, planned a getaway to Las Vegas with his girlfriend, Heather Cooper, his 9-year-old son, Brady, his 14-year-old daughter, Ashton, and Ashton’s best friend, 15-year-old Taylor Tuttle. The trip was to see a pair of Michael Jackson-themed shows: “MJ Live” at the Stratosphere on Sept. 30 and Cirque du Soleil’s “Michael Jackson ONE” at Mandalay Bay on Oct. 1.

The mini-vacation was a surprise for the kids. The adults left them notes as clues about where they were going. One read, “Something you see on this trip will be very ‘Bad.’”

“I was using the song title as a clue, and now of course it has an entirely different meaning,” Nelson said.

The show halted during the “Billie Jean” number. The audience was informed there would be a delay. The show never resumed.

“The kids turned around, looking for something happening in the show, because there is a lot of audience participation,” Nelson said. “But after eight or 10 minutes, people started realizing by looking at their phones that something was really wrong, and there was a shooter upstairs at the hotel.”

For many minutes, audience members took cover in the theater’s rows and aisles and awaited directions from hotel security and arriving police officers.

At about 1:30 a.m., the first group of audience members was allowed to leave the theater for a shuttle to the Thomas & Mack Center, where those displaced by the incident were being sent. Because of the minors in the group, Nelson’s party was on the first bus out.

“The only thing I can compare it to is that final scene in ‘Titanic,’ walking through all of the survivors trying to get to lifeboats,” Nelson said. “People in the lobby were shoulder-to-shoulder, waiting to get out. … It was the first time in my life where I felt I could not guarantee my own children’s safety. We were all just in react mode.”

— John Katsilometes

‘This is my hometown’

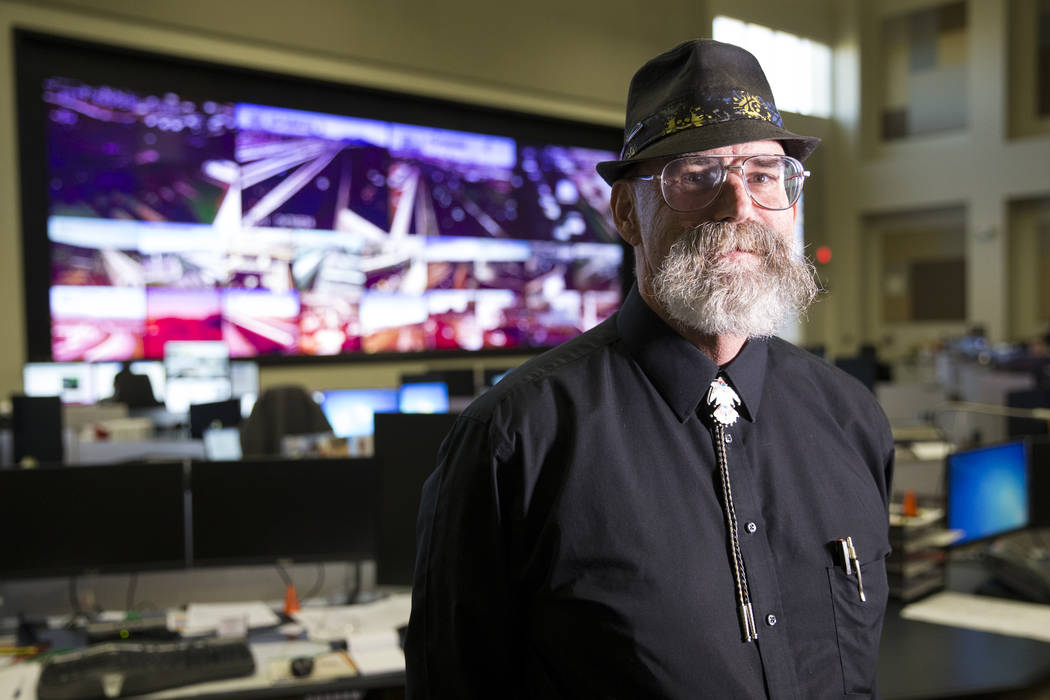

David Crisler was jolted awake at 12:20 a.m. Oct. 2 by a phone call telling him to report to work at the region’s traffic nerve center.

Crisler had gone to bed early, so a Nevada Highway Patrol dispatcher quickly shared some information about the shooting.

The rest of the story was filled in by news reports Crisler heard on the radio as he drove to the Regional Transportation Commission of Southern Nevada’s traffic management center, just three miles southwest of Mandalay Bay.

When Crisler took his seat in front of the wall of widescreen televisions at the traffic center, Las Vegas roads were in a condition he had never seen before.

Major roadways were closed to traffic, and long stretches of Interstate 15 would stay that way overnight. It would take 44 hours for Las Vegas Boulevard to completely reopen to vehicles.

“I don’t remember a time when any part of the Strip was closed for this long, certainly not for any kind of event like this,” said Crisler, a Las Vegas native.

To compensate, signal timing was changed for “a couple dozen intersections,” including parts of Tropicana Avenue, Koval Lane, Paradise Road and Russell Road. Updates about closures were posted on digital signs, shared on social media networks and sent via email to local residents.

Meanwhile, other parts of the high-tech system intentionally went dark: Signal-mounted cameras that normally stream live footage of traffic were turned away from the shooting scene as police investigated.

“This is my hometown. These are people I live and work with on a daily basis, so there was certainly that concern,” Crisler said. “But the only thing I could do to help the situation was to do my job and see to it that our part was handled the best it could.”

— Art Marroquin

‘I bet whatever happened was bad’

Nevada Highway Patrol Trooper Travis Smaka said the decision to block traffic on I-15 “saved hundreds of lives,” including at least one he knows of personally.

Shortly after the shooting, Smaka spotted a pickup truck swerving on Sunset Road near Las Vegas Boulevard. A woman hanging outside the passenger window waved at him to slow down, pleading for help.

A seriously wounded woman was riding in the truck’s bed and needed to get to a hospital.

Smaka flipped on his lights and sirens and, with the pickup following close behind, headed in the direction of University Medical Center. He was relieved to find that his fellow NHP troopers had closed much of the interstate to clear a path for emergency vehicles.

He led the way north on the freeway to Charleston Boulevard and on to UMC, where the shooting victim immediately underwent surgery.

She survived, the family later told Smaka.

“They have told me, unequivocally, that if it wasn’t for the speed in which I was able to get their daughter to UMC trauma, she wouldn’t have made it,” the trooper said. “I attribute my ability to get them there as soon as I did to having the 15 shut down.”

The decision left scores of motorists stranded on the interstate for hours, many of them with no idea of the scale of the attack that had unfolded just miles from where they sat. Confused drivers climbed out of their vehicles to take pictures and chat with one another.

“I’m literally standing on the freeway right now,” one woman said, her phone pointed at her feet as she walked from one side of the highway to the other.

“Dude, I bet whatever happened was bad,” a driver of a white sedan shouted from his window at two men sitting on a concrete wall dividing the northbound and southbound lanes.

Before the men could answer, eight more emergency vehicles flew by on the shoulder of the interstate.

— Art Marroquin and Rio Lacanlale

‘Stay put, stay put’

“Fantasy” adult revue producer Anita Mann was in the show’s theater at the Luxor and unaware of the shooting when she took her seat for the 10:30 p.m. performance.

She got word about the gunman at Mandalay Bay about 10 minutes later.

Mann sent word to singer Lorena Peril to notify the audience at the end of the performance that they would not be able to leave.

“So we had an entire room full of people who were not fully aware of what was going on, other than it was happening near the Luxor,” Mann said.

After the show, the cast and crew kept performing to entertain the captive crowd.

“Lorena sang the ‘Fantasy’ theme song. Sean E. Cooper (the show’s comedian) did ‘Proud Mary,’ and we played the opening montage. We just did everything we could to keep people comfortable.”

The cast also passed out candy to audience members. Luxor execs delivered boxes of bananas and bottled water to the crowd, which was in lockdown until 4:30 a.m. — some six hours after being seated.

Mann said what she’ll remember most is the feeling of unity in the audience.

“We had people inside the theater asking about how they could help, where they could start to give money and where to donate blood,” Mann said. “They would have done that from their seats if they could.”

Mike Tyson also continued through his show, “Undisputed Truth: Round 2,” at Brad Garrett’s Comedy Club at the MGM Grand Underground promenade. The club is actually underground and thus insulated from most activity on the Strip or the nearby casino floor.

Room manager Anthony Pecora of SPI Entertainment of Las Vegas said he felt people rushing through the Underground a little after 10:20 p.m., but he was unsure what was unfolding upstairs. “We just kept being told, ‘Stay put, stay put,’” Pecora said.

Tyson continued to perform even as the hotel itself — including the Ka Theater and David Copperfield Theater — was in lockdown.

“The decision was: Do we keep going or do we stop?” Pecora said. “After talking to security, we knew the show wasn’t being targeted, and there were no security issues inside the theater at that moment, and we went to the absolute end of the show. We were totally insulated from everything else.”

— John Katsilometes

‘Shooter, shooter, shooter’

Xavier Burkett started his Oct. 1 shift at Sundance Helicopters at 6 p.m. The detailer was washing helicopters on the flight line when he took a break around 10 p.m. to refill the soapy water.

That’s when he heard a sound he told himself couldn’t be gunfire. He figured Mandalay Bay must be setting off fireworks again.

Soon, though, the cracking sound was joined by the wail of sirens.

Sundance pilot Tara Sturm was waiting for the last scheduled tour of the night when a group of girls rushed into the Sundance lobby screaming, “Shooter, shooter, shooter.”

Sturm called 911. Then she called her wife.

She saw hundreds of people run out onto the airport property. She had to get everyone inside quiet and calm.

Some of the concertgoers were too frightened or too drunk to listen. A man covered in blood wandered off.

Meanwhile, outside, Burkett waved down people fleeing from the gunfire. He wanted to bring them inside Sundance’s building, but his security code wouldn’t open the door because the facility had gone into lockdown.

People panicked. A woman tried to scale a ladder on the side of the building. A man threatened to hurl a trash can through the front window. Another woman in a black Tahoe said she was going to plow through the barbed-wire fence leading to the helicopters.

Burkett climbed up on the Tahoe hood and tried to take control of the situation. He convinced about 20 people to hide with him in the bushes until one of his coworkers unlocked the door and let the group inside.

Sturm still felt the adrenaline as she drove home later. She said it took about 24 hours for the shock to wear off, but other feelings lingered.

At times, Sturm still finds herself crying on the way to work, but she’s encouraged by stories of strangers helping strangers at Sundance and around the Strip that night.

“The majority of humanity is good,” she said. “I would say that inherently we are good.”

— Wade Tyler Millward

‘We saw the chaos’

White crosses bearing the names of the 58 victims in the Oct. 1 shooting now stand near the city’s iconic “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas, Nevada,” sign.

But at 10:15 p.m. on Oct. 1, the site was filled only with police officers and Nancy Aguilar, who was desperately searching for her husband.

Just 10 minutes before, she was on the phone with him.

“He called me. He said, ‘Can you see the news? Can you see what’s going on?’ All I could hear was gunfire in the back,” Aguilar said. “I said, ‘Where are you? What’s going on?’”

Lucas DeLeon was tending bar at the Route 91 Harvest festival. His shift was scheduled to end at 10 p.m., but he decided to stay on a little longer until his next job on the Strip started.

When the shots rained down on the crowd, he started running. And he called his wife.

Aguilar and a friend who lives close by hightailed it in her car toward the Strip, which was only a few minutes away.

Some roads had already been closed, so they found a back way in: Dean Martin Drive to Blue Diamond Road and then north on Las Vegas Boulevard to the sign.

“The whole time, that whole time, I wasn’t able to speak with him. I don’t know what happened. He wasn’t getting signal or I wasn’t getting signal,” Aguilar said.

Worry turned to relief when her daughter called to say that her brother was on a Facetime call with their dad.

DeLeon was still walking away from the venue, when police told Aguilar and her friend to leave the sign and head south.

They ended up in the parking lot of a Jack in the Box restaurant a half-mile away.

While she waited for DeLeon to make his way to her, they saw other people walking in their direction — bloodied and frightened, asking for help.

She also overheard phone calls of people who were trying to locate children, friends and relatives.

“We saw the chaos,” Aguilar said. “People calling, saying, ‘Are you OK?’”

When DeLeon finally made it to the parking lot after 2 a.m., Aguilar was relieved.

“It just felt like an eternity,” she said.

— Natalie Bruzda

‘She was our angel’

Matt and Robyn Webb escaped the Route 91 Harvest festival grounds only to be caught in a stampede inside the Hooters Hotel.

Robyn was knocked to the floor and had a woman land on top of her as at least 100 people surged through the casino to escape what they thought was more shooting from another gunman.

Matt pulled his wife to her feet, and the couple from Orange County, California, made their way outside, where they hid trembling in some bushes at the edge of the parking lot. That’s where Hooters waitress Darrellyn Blake found them a few minutes later and offered them a ride.

“She didn’t know us. She didn’t have any reason to help us. But she said, ‘Get in my car. I’ll get you away from here,’” Matt said.

The Webbs returned to Las Vegas from Southern California on Thursday to pay their respects at the memorial at the Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas sign.

Seeing that line of crosses only stoked their survivor’s guilt, but they also hope it will help them find closure.

“We were in complete survival mode” that night, Matt said.

“We were just trying to make sure our five kids still had parents,” Robyn added.

On Saturday, the Webbs headed to the Hooters Hotel for a tearful reunion with the 22-year-old woman who helped them that night. They brought a bouquet of white flowers to thank her.

All Blake did was give a couple of desperate strangers a lift to a gas station a mile and a half away, but the distance and the gesture meant the world to them.

“She was our angel,” Robyn said. “She was the safest we felt that night.”

— Henry Brean