A uniquely Vegas idea: The Mob Museum turns 10

Former Mayor Oscar Goodman was trying to convince a group of Italian Americans that he had a good idea: He wanted to turn a Depression-era federal building into a museum about mobsters.

They didn’t think it was so ingenious. And they pressed so hard against the topic, Goodman recalled, he ended up caving.

“It got to the point where I said, ‘A mob museum? What are you talking about? I said a mop museum,’ ” Goodman said.

Despite the early opposition, the project, formally known as the National Museum of Organized Crime and Law Enforcement, became a reality and celebrated its 10th anniversary on Monday.

Like many mafia stories, the history of the museum had its fair share of fans and detractors.

A uniquely Vegas idea

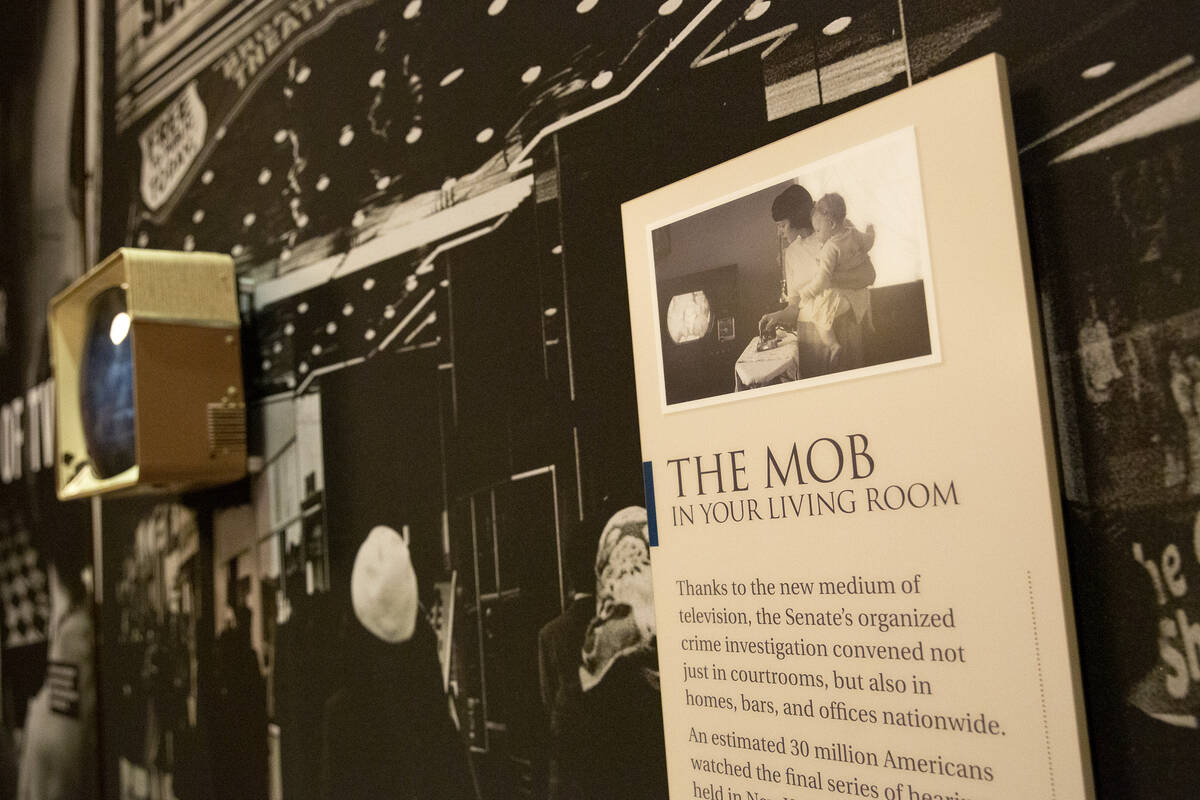

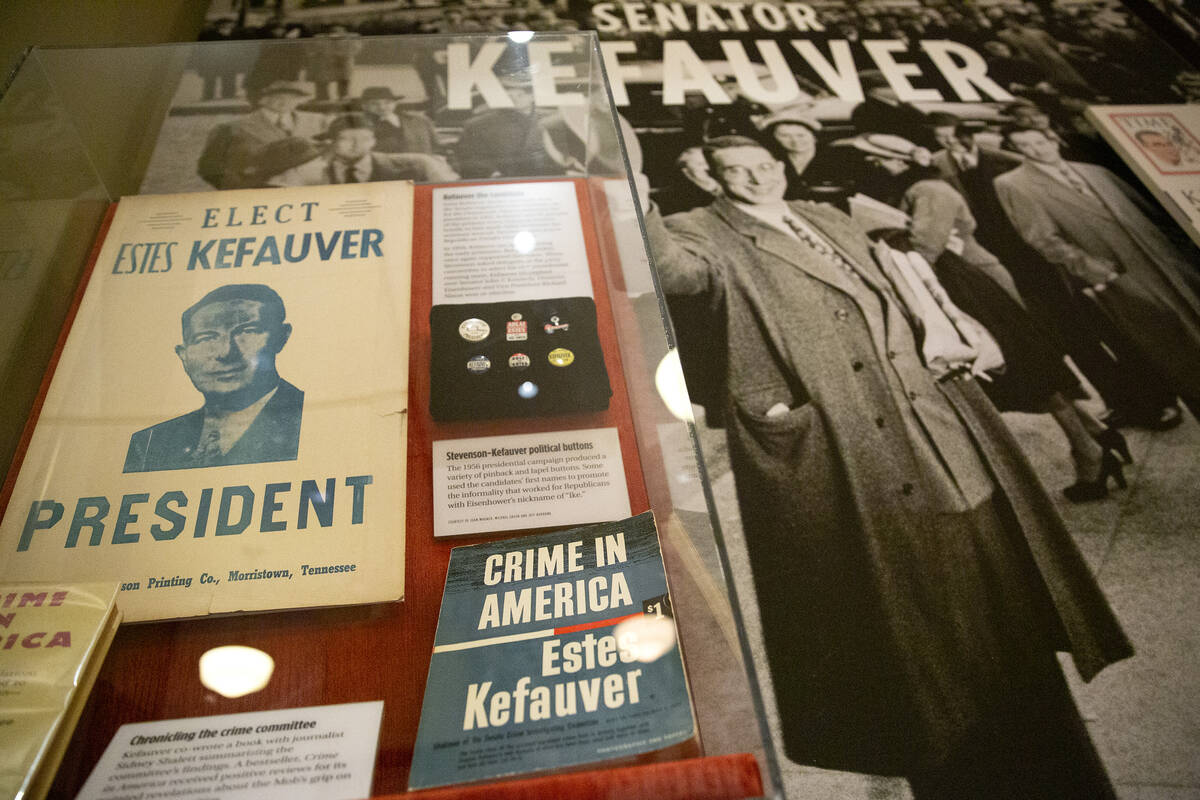

In 2002, the city purchased the federal building on Stewart Avenue, which once housed a post office and courtrooms, where even the Kefauver Committee held hearings investigating organized crime.

Goodman said it was crucial for him to restore a historic Las Vegas building — one of the few to be saved compared with older cities on the East Coast.

“I made a promise to myself. I got the support of the council,” he said in an interview with the Review-Journal. “We weren’t going to destroy any old buildings like they were doing out on the Strip. We were going to try to keep everything intact.”

Goodman, a former defense attorney for reputed mobsters, knew the topic could attract a wide audience. But locals were concerned with the reputation a museum about the mob would place on the city.

A 2005 poll surveying 600 locals and 300 tourists found a majority of Southern Nevadans preferred a museum about vintage Vegas, but 70 percent of tourists liked the mob theme, according to Review-Journal archives.

The museum team knew visitation at museums was dominated by tourists, said Jeffrey Silver, chairman of 300 Stewart Avenue Corp., the nonprofit that runs the museum.

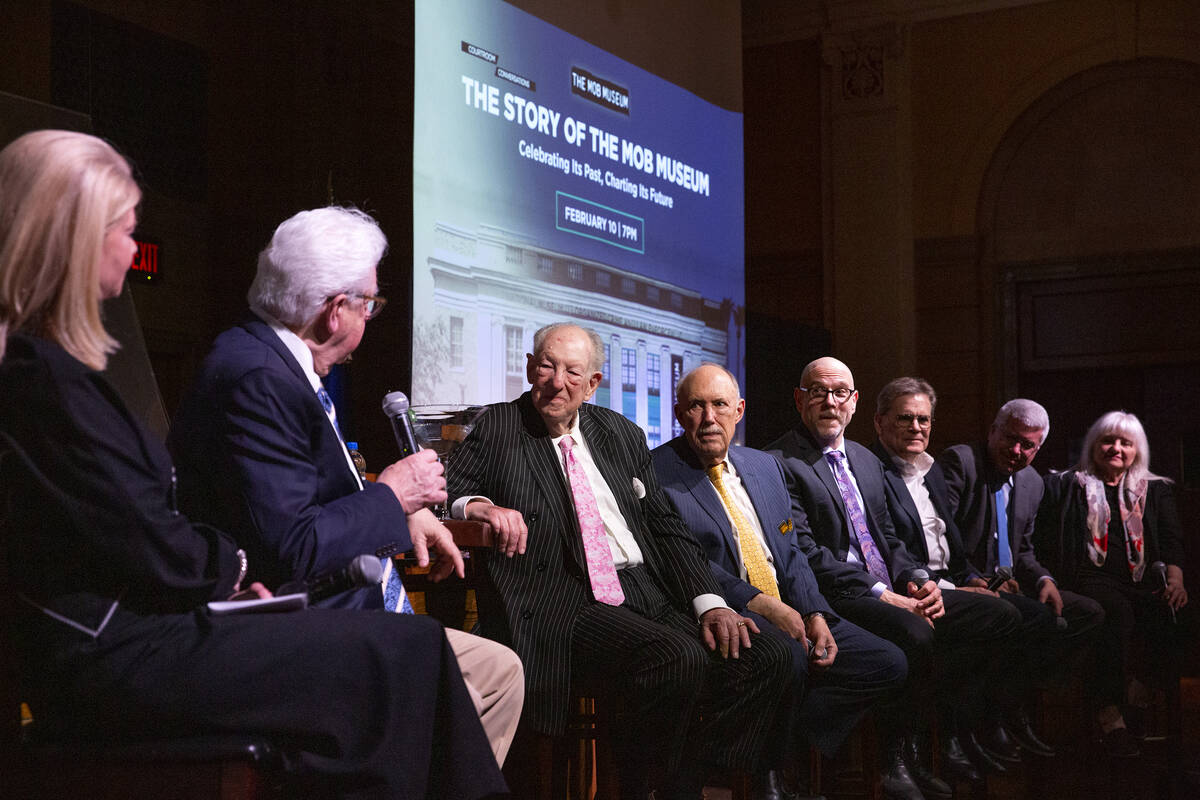

“They’re all coming from somewhere else, going to a museum as a part of their view of the city or entertainment,” Silver said at a panel Thursday discussing the museum’s history. “In this particular case, Las Vegas was an open city and for organized crime, they came from all different parts of the country. They brought with them their organized crime issues that were all a fascination for the local people that live there.”

What spurred support of the museum was the team behind it, Goodman and others said. Leaders like Ellen Knowlton, former special agent in charge of the FBI’s Las Vegas division, and Dennis Barrie, a creative director who previously worked on the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, gave credibility to the project and showed skeptics the idea would be even-handed.

The $42 million project took about 10 years and a patchwork of local, state and federal funding to complete. Even the funding had a bit of a mob flair. When it came time for the museum to pay back a portion of the city’s investment — initially given through the Federal Historic Tax Credit Program — Goodman brought $1.5 million in a handcuffed briefcase and satchel to City Hall, Review-Journal archives showed.

Expanding the museum

Now, more than 3 million people have visited since its opening 10 years ago, spending $21.5 million annually in downtown Las Vegas, according to a 2020 museum report.

A $9 million renovation, completed in 2018, expanded the museum’s presence. Experiential exhibits were added like The Underground, a speakeasy and distillery in the building’s basement that gives visitors a lesson on the Prohibition Era.

It’s unique for its ability to attract people who may not go to the museum otherwise, and bring them in after-hours through a new revenue stream, Mob Museum President and CEO Jonathan Ullman said.

“We want the people that come to the speakeasy, that are attracted to the speakeasy first to also be curious about the museum and then become fans of both,” Ullman said, noting The Underground accounted for about 15 percent of its 2021 revenue.

The last decade has still seen challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic shut the museum’s doors for three months in 2020 at an inopportune time, Ullman said. Attendance in 2019 was about 410,000 and the first two months of 2020 saw record visitors.

The pandemic forced much of the museum’s educational outreach and programming online. Attendance has steadily increased since lockdowns were lifted, ending 2021 at about 85 percent of 2019’s total, Ullman said.

“We’ve weathered the storm perfectly OK,” he said. “It’s had a lot of distress with the ebbs and flows of it all. We’ve also seen that the people that are coming, they’re doing more than they would do historically. The spend is up.”

Looking ahead

Ullman said he’s proud of how much innovation the museum has done in the past decade. The staff added exhibits on use-of-force and forensic science along with The Underground during the 2018 renovations. They’ve also created more educational outreach and will have its first-ever fundraising gala on Thursday.

But the additional 3,500 square feet of exhibits has posed a new challenge for the museum: It’s running out of space. Ullman said the future of the museum is growing outside of its stone walls, possibly creating an outdoor plaza for events, among other ideas, that would be adjacent to the property.

Museum officials also expect exhibits to evolve, just as organized crime.

“It’s not something that we should be happy about, but there’s no end in sight for organized crime and for what law enforcement has to do to try to combat it,” Ullman said. “There are already way more stories than we could possibly tell about the past 100-plus years that we cover in the existing museum, but there’s more and more every day.”

McKenna Ross is a corps member with Report for America, a national service program that places journalists into local newsrooms. Contact her at mross@reviewjournal.com. Follow @mckenna_ross_ on Twitter.