Amid COVID-19 lockdowns, Americans everywhere wondered whether unrest would result from the grave public health crisis and financial effects of prolonged time at home.

But it was the May 25 death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers that inspired protests in all 50 states.

Now, as the pandemic, protests and quiet personal reflections on racism vie for our attention, black artists in the Las Vegas Valley say that we can find comfort and a stronger sense of empathy by familiarizing ourselves with the works of artists of diverse backgrounds.

If you look at art, you think about the reasons the artist created it.

Vicki Richardson

“If you look at art, you think about the reasons the artist created it,” says Vicki Richardson, founder of Left of Center Art Gallery in North Las Vegas. “You gain more respect for the person and the imagery. This is a very trying time. And I think art really does have the ability to heal.”

Through paint, poetry, performance and photography, these five Las Vegas artists channel empathy by illustrating their investigations of loss, perception and beauty.

Brent Holmes

In exploring the theme of history, Brent Holmes uses diverse media.

“I can say that the primary body of my work from 2015 until now addresses all of the issues extant in the current civil unrest,” Holmes says.

For a recent show, he built a water fountain out of ceramic and steel. He provided an activated charcoal face mask and invited visitors to rub the black scrub into their skin while music by a black composer played.

Holmes titled the project “Clotilda,” named after the last slave ship to land on U.S. soil.

The idea was to provide a recursive experience for the audience. What if, by wearing blackface, a person were granted black consciousness and the perceptions, anxieties and difficulties that black people experience?

I can say that the primary body of my work from 2015 until now addresses all of the issues extant in the current civil unrest.

Brent Holmes

The project is one way that Holmes investigates empathy in his work.

“Empathy is the great conqueror of strife,” Holmes says. “It is the purest form of human intimacy. Understanding another person’s perception is a powerful manifestation of love.”

Holmes says that the job of an artist is to be an “internaut.” Where the role of an astronaut to explore what lies beyond, an artist’s job is to explore within.

“Our job is to go in and dig around in there, then bring what we find out into the world and describe it as accurately as possible,” he says.

Holmes has attended several Black Lives Matter protests in Las Vegas as a photographer for Nevada Public Radio. He has not yet created art in response to that movement, but he expects to work on performance art with the organization he co-founded, RADAR, after having had time to process.

He says he has perceived performance art within the protests, themselves.

“At one of the protests, there was a line of police, and protesters were kneeling and asking the police why they wouldn’t join them,” Holmes recalls. “That’s what a lot of performance art looks like, a series of actions that confront an idea.”

Shereene Fogenay

A lifetime of experiencing microaggressions had left Shereene Fogenay feeling she could not fully express herself.

“If I’m passionate, I get called angry,” explains the Las Vegas artist. “If I express knowledge, I’ve been told I’m ‘really smart for a black person.’ As I got older, I didn’t feel comfortable showing emotion because it comes off different when you are a person of color.”

With watercolor, ink and water-soluble pencils, Fogenay creates portraits in black expression, assigning real and complex emotions to her characters.

In her painting titled “He Looks Up,” Fogenay used watercolor to depict a man craning his neck to gaze upward, as though looking for something more.

If I express knowledge, I’ve been told I’m ‘really smart for a black person.’ As I got older, I didn’t feel comfortable showing emotion because it comes off different when you are a person of color.

Shereene Fogenay

Fogenay says she was inspired by the vulnerability she sees in the men in her life. Since painting it, she says the image has taken on new meaning.

“I feel like it’s relevant today because this piece to me shows that this man is vulnerable,” Fogenay says. “In connection to police brutality, these men are most likely not criminals. This man loves his family and is trying to provide like anybody else.”

In the last two years working at the Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art, Fogenay has learned more about Japanese art than she did while studying art at the College of Southern Nevada.

She found that, in delving deeper into Japanese artwork, she found connections to themes and practices artists use today.

“By looking at work of other artists, you’re opening your horizons to their ideals,” Fogenay says. “In discovering other cultures, you’re inherently understanding yourself.”

Chase McCurdy

Chase McCurdy practices his art in a place of contradiction.

He says that the balance between freedom and discipline in which he writes and draws every day extends from his practice to his daily life, as he strives to identify ways to carry a positive momentum.

When he is not creating artworks, like those currently on display at the City Hall gallery, the commercial photographer volunteers his time to teach art to what he says are other marginalized communities: children and senior citizens.

One of his 2018 pieces is a staged photograph, showing an American flag suspended by a thin string and backlit by a bright window.

I look at it as a country in distress. As a historical piece, there’s a legacy of lynching.

Chase McCurdy

He says the image could carry several meanings.

“I look at it as a country in distress. As a historical piece, there’s a legacy of lynching,” McCurdy says.

Looking at the photo now, he wonders at what the light from the window could stand for. “I see the green of the plant and the new light coming through, like a new horizon.”

The artist prefers to use abstract imagery over recognizable forms.

“A lot of artists I love and champion represent African American people in their art,” McCurdy says. “What I gain by using abstract shapes is the ability to potentially connect with a broader range of individuals.”

His choice speaks to another contradiction, that often black artists are grouped into one category and not afforded the same individuality as more mainstream contemporaries. He hopes his abstract images will engage audience members in a way that is more conversational.

“I am more than willing to challenge you,” McCurdy says. “I want you to interpret this but I’m not going to spoon-feed it to you. We’re going to meet halfway and explore it together.”

Lance L. Smith

Lance L. Smith’s interest in art originated as a child with comic books. As an adult, Smith uses paint and illustration to investigate ideas of loss, distortion and adornment.

Smith’s first exhibition focused on their mother, who passed away when the artist was young.

Smith developed small square paintings using images they remembered from childhood.

“I investigated older images and saw that she wore certain earrings,” Smith says. “The paintings acknowledge that memory. As a small child, that adornment spoke to the femme that lived in me.”

In another collection, Smith took inspiration from the work of author James Baldwin and created images of animals to represent ideas of moral apathy.

The paintings acknowledge that memory. As a small child, that adornment spoke to the femme that lived in me.

Lance L. Smith

Smith’s series of big horn sheep speak to that theme, informing that audience that, in this moment, nature is watching what we choose to do.

In creating and showing art, Smith questions the inequities of opportunity.

“Upwardly mobile cisgender white men can get inspiration anywhere,” the artist says. “They have access to land art. They can literally move the earth. For women and people of color, it’s much harder to get that space.”

Smith says diverse artwork offers a chance for audiences to experience ideas they may not otherwise encounter.

“Good artwork is a portal,” Smith says. “You’re getting to a place where you’re learning. And that brings change.”

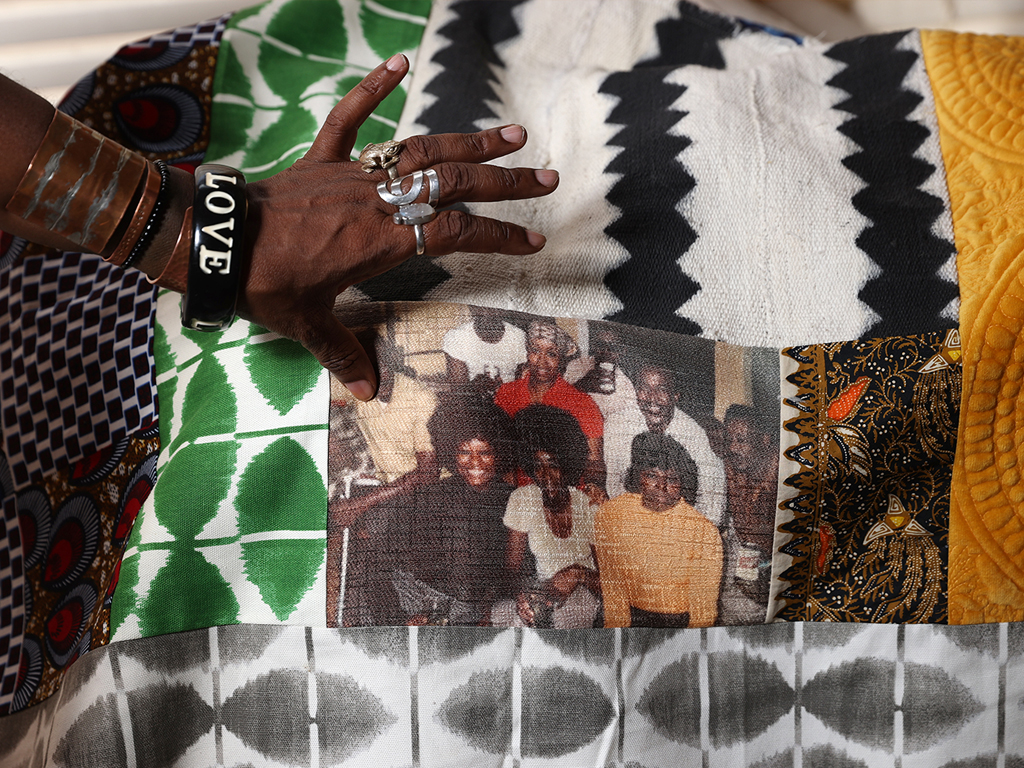

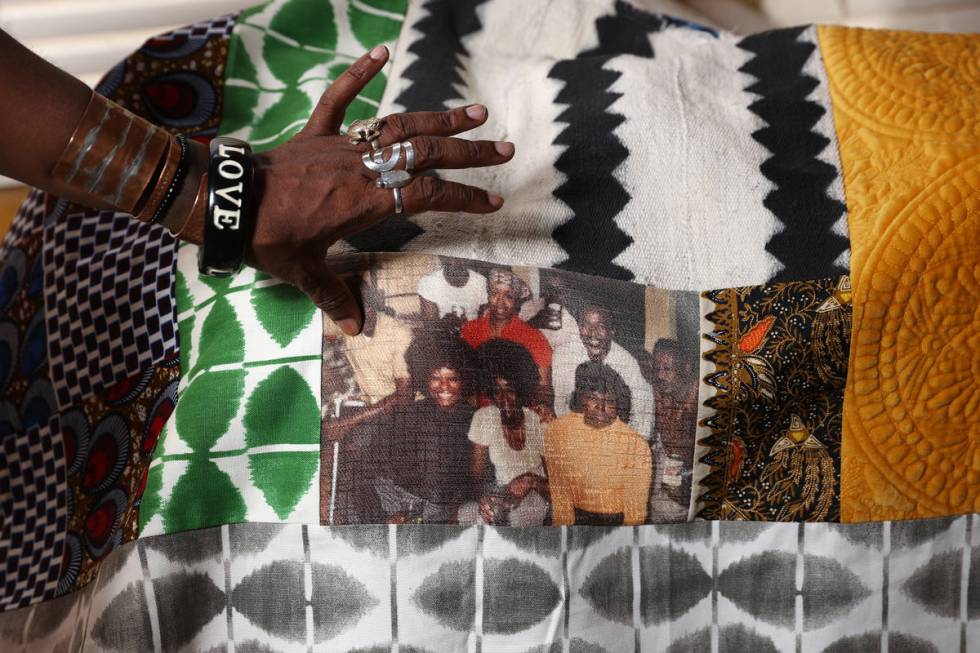

Erica Vital-Lazare

Erica Vital-Lazare grew up in the projects in Hampton, Virginia, with her mother and two older sisters. Their front yard amounted to little more than a 15-square-foot sandbox.

Every day, Vital-Lazare’s mother would have her go outside with a rake, and beautify the little plot of land.

“For me, that encompasses the need to make the hard thing beautiful,” Vital-Lazare says.

The 52-year-old artist and writer came to Las Vegas in 1994 after earning her master of fine art degree from Virginia Commonwealth University. Today, she teaches creative writing at the College of Southern Nevada.

Earlier this year, she collaborated with artist Lance L. Smith to write a poem and create visual art for an exhibition on grief through Nevada Humanities.

To be black is to be aware that there is not only beauty in surviving, but also in surviving so beautifully.

Erica Vital-Lazare

“For me, what that exhibit did was highlight the diversity of the arts community here in Las Vegas,” the artist says. “There was a shared humanity. I think that’s what art is meant to do.”

Vital-Lazare’s writing is rooted in Southern imagery, like the places where she grew up. She writes about memory and family and the question of history and how that history continues to shape us.

“As a black woman, I’m informed by a past that is rooted in enslavement and brutality,” she says. “To be black is to be aware that there is not only beauty in surviving, but also in surviving so beautifully.”

She says developing sensibility for what blackness has done for the country is to offer all artists a springboard to be their authentic selves, no matter what skin they are in.

“The fact that, after hundreds of years of repression, of dehumanization, that we can stand as we stand, and paint as Lance paints and take haunting pictures like Brent Holmes and do all of these things centuries later, that our forebears did, it frees and empowers all artists.”

Contact Janna Karel at jkarel@reviewjournal.com. Follow @jannainprogress on Twitter.