Book festival bring authors and lovers of words to downtown

There’s something about the look and feel of a book that can’t be duplicated by a screen. But, boy, those techish things sure can come in handy in a pinch.

Take the Las Vegas Book Festival. Thanks to the COVID pandemic, last year’s festival went all virtual, and while it wasn’t quite as much fun as wandering among the outdoor tents at the Historic Fifth Street School, it worked pretty well.

So well, in fact, that this year’s 20th anniversary edition of the festival will include both formats. First, from Monday through Friday, a slate of online events will make up what the festival organizers are calling “Virtual Reading Week.” Then, on Saturday, the live, in-person Las Vegas Book Festival returns with its usual all-day array of workshops, speakers, readings and activities. The festival will run from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. at the Historic Fifth Street School, and it’s all free and open to the public. For more information, visit lasvegasbookfestival.com

Ally Haynes-Hamblen, cultural affairs director for the city of Las Vegas, is pleased to have the festival “back in person and looking a little more like it used to.” Saturday’s events will include a few new offerings, including chef demonstrations and more focus on the romance genre, which, she says, “we haven’t had at the book festival for a while.”

Panel discussions and presentations remain a solid part of the festival. “Every year when we get started I have that fear, like, ‘Are we out of ideas? We’ve covered it all,’ and every year … it’s inevitable that we can’t fit it in and we have to pare it down,” Haynes-Hamblen says. “We live in such a bizarre and complicated and interesting world right now that there’s always going to be something new to talk about.”

And, as always, the festival features addresses by big-name authors Saturday. This year’s keynote speakers are Fran Lebowitz, Sandra Cisneros and Dr. Oriel Maria Siu.

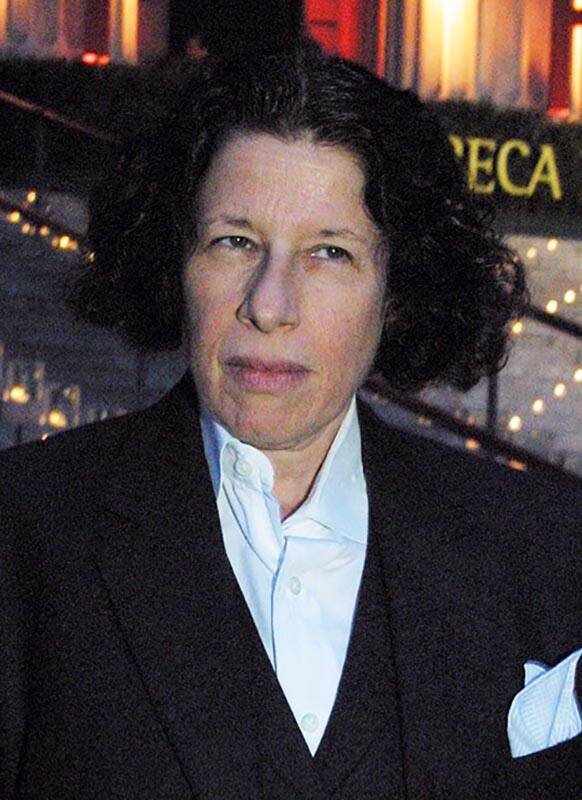

Fran Lebowitz

Strange times call for sharp social commentary, and Fran Lebowitz has spent decades covering strange times with razor-sharp wit, brutal honesty and welcome snark.

Her first collection of essays, “Metropolitan Life,” was published in 1978, followed by a second collection, “Social Studies,” in 1981. Both since have been combined into “The Fran Lebowitz Reader,” which has — along with the 2010 HBO documentary “Public Speaking” and the 2021 Netflix series “Pretend It’s a City,” both directed by Martin Scorsese — introduced Lebowitz to a generation of fans who weren’t even born when she was a columnist for Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine.

But Lebowitz doesn’t read much into that. “I think, truthfully, it’s because of this Netflix series is what’s causing all of this attention,” she says. “But I was alive before Netflix. I’ve always had young audiences. I’ve never truly understood, and I don’t understand it now.”

One theory: “Being in New York when I was younger, in the ’70s, has become this glowing era to people who are young. For decades, young people have been stopping me on the street saying, ‘Oh, I wish I lived in the ’70s.’ There are certain eras that achieve this kind of cultural attraction for people. I think that’s a lot of it.”

And that Netflix collaboration with Scorsese? “I don’t have Netflix, but I didn’t realize how gigantic it was. It’s all over the world. Also, I profited by the mistake of coming out during the height of the pandemic. It happened to come out when the entire world other than me was watching Netflix.”

During the festival, Lebowitz will participate in a conversation with local attorney and writer Dayvid Figler and then take audience questions. “They’re actually my favorite activity, not just in public speaking but in general,” Lebowitz says. “It probably started with laziness, as most things in my life do.”

Lebowitz has traveled a bit during the pandemic but mostly has stayed close to home. “I did have a date in Texas next week, but I canceled it. I looked at COVID rates and said to my agent — and, by the way, I’ve been doing this since I was 27, and I’m 70 — I didn’t know I could cancel a date. I’ve never canceled a date, but I said I’m not going to a place where COVID rates are sky high and it’s illegal to wear a mask but perfectly legal for people in the audience to have an assault rifle.”

She does see a sharply divided country out there. “I think the last time this country was in this bad condition was before the Civil War. I’m not that old, I can’t regale you with tales of the Civil War, but it looks to me that this country is very divided.”

In addition to those Scorsese projects, TV viewers may recognize Lebowitz from “Law & Order,” on which she had a recurring role as a judge.

“I get royalty checks from countries that I have to look up,” she says. “I did that, I think, about a dozen times. I did it because I wanted to wear the judge’s robe.”

Sandra Cisneros

Sandra Cisneros had the high school students she was teaching in mind while writing her 1984 novel “The House on Mango Street.” But in the years since its publication, the story of a 12-year-old Chicana girl growing up in Chicago has resonated with readers of all cultural backgrounds and among adults.

“No one is more amazed than me,” says Cisneros, who calls the novel “a cross between poetry and prose. It allowed me to find my voice.”

Cisneros will appear virtually during the festival to discuss the novel, which has been selected for the National Endowment for the Arts’ Big Read program.

Cisneros says she’s become accustomed to having virtual meetings with readers over the past year. “It’s just a weird time. Since the end of July I’ve been Zooming nonstop.” On the upside, she jokes, “it’s writer’s heaven to be isolated. Finally, I have an excuse. I’m used to having to make up excuses.”

Cisneros had no idea that “The House on Mango Street” would be embraced by so many. But, she says, it was “written with my heart, and what it has taught me is whatever is created from that place of true love is the highest work we can do.”

The novel also helped teach Cisneros about the power of an honestly told story. “I think I, like many teachers, felt upset by my impotency to affect their lives — what good is literature and teaching them how to write poetry?” she says. “Now I know art can change people’s lives. We who are writers hope that our notes in a bottle will reach the right person.

“I’m naively optimistic,” she adds. “I have to believe, and there’s something about me being eternally the child. I keep waiting for the inner adult to kick in. It hasn’t arrived yet, and know what? It works for me.”

Dr. Oriel Maria Siu

When Dr. Oriel Maria Siu was searching for children’s books for her own daughter, she wasn’t impressed with most of what she found.

Siu, then a college professor of ethnic studies, wrote her own children’s book with its own appealing heroine. The result was “Rebeldita the Fearless in Ogreland,” in which the ever-questioning multicultural heroine faces off against ogres who have a fondness for building walls and separating children from their parents.

There’s now a second book — “Christopher the Ogre Cologre, It’s Over!” — in what Siu plans to be a series. She became an accidental children’s book author in 2013 when, Siu says, “I became a mom to a Black and Chinese and Indigenous child.”

She was living in Seattle, which “has some amazing libraries. So I was looking for books.”

“I found the majority of books continued to center around the experience of white children and did not accurately represent the lived experience of children of color, and if they were present, they were shallow representations of diversity.

“As an academic, I started to look into it and I found a huge problem in children’s literature in the United States. It touched a part of me because I really love reading, and I said, ‘Why is this?’ I decided I needed to start writing for my daughter.”

The result is Rebeldita, who is “Black and Indigenous and she’s from the Americas,” Siu says. “She came to this world to show us real history and make us question borders and family separation. Why do some children get to stay and others get separated from their families? She comes to question.”

Does she ever hear that such topics are too intense for kids to handle? That, Siu says, has been a question posed only by her white students. But, she continues, “native, Indigenous children have this conversation on a daily basis. They actually live these realities of their land being occupied. Black children and parents have conversations about race all the time.”

It’s not about creating guilt, Siu adds, but promoting conversation.

“I believe it’s a matter of how we facilitate the discussion, and that’s how literature can come in handy, because it allows us to create a language that invites as opposed to pushes back,” she says. “My books are invitations to parents, teachers of children and their parents, to explore the Americas from perspectives that have been silenced.

“My books are an invitation,” Siu adds. “No story is closed. They end with an invitation to participate in it. You and I are as much part of the story as Rebeldita is.”

Contact John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com. Follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.