Exhibit spotlights art, life of Frida Kahlo

Passion and pain pour from her paintbrush.

They inform her delicate face, sprouting antlers. They ripple through her sleek, animal physique mounted on four legs, arrows protruding from the deer with the human visage, wounds seeping blood.

Know thyself? Frida Kahlo did.

"She lived in a lot of physical and emotional pain," says Atzimba Luna, consul for community affairs for the Mexican Consulate in Las Vegas. "This exhibit walks you through different stages of her life, so you get to know her not only as an artist and this iconic figure of contemporary art, but the complex and tormented person she was."

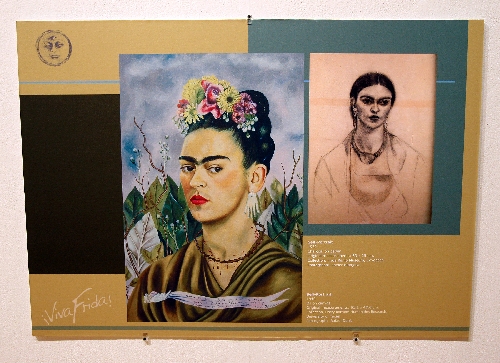

That exhibit is "Viva Frida," on display at the Barrick Museum at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, marking the centennial of the Mexican Revolution.

"She was also very much involved in the political life of her time, the revolutionary times when everything was happening," Luna says from the consulate, which is presenting the exhibit. "She left a deep imprint in the art, something you immediately relate to as Mexicans. The color, the topics of her paintings, it is very infused with a Mexican identity."

Described as both folk artist and surrealist -- one colleague described her as a "ribbon around a bomb" -- Kahlo endured considerable anguish, much of that emotion emerging in her art.

Suffering from polio as a child, there's speculation she also battled spina bifida, a congenital disease affecting spinal and leg development. A teenage Kahlo was aboard a bus that collided with a trolley, leaving her in such a horrible condition that she had to recover in a full body cast, during which time she painted to pass time.

Playing on a continuous loop in the museum's screening room, that chapter of her life is chronicled in "Frida," the 2002 film starring Salma Hayek. "Right now I'm a burden, but I hope to be a self-sufficient cripple someday," she tells her father in the film, later rising out of her wheelchair to haltingly walk right into the joyful embrace of her parents.

Turbulence also ripped through her two marriages to painter Diego Rivera, rife with each's extramarital affairs -- hers with both men and women, including Josephine Baker, his including one with Frida's sister -- and fiery fights.

"I had two bad accidents in my life," reads one Kahlo quote. "The first was when the trolley crashed. The second was Diego."

Emotionally and physically, it's all mirrored in the many self-portraits and portrayals of the couple hanging on the Barrick walls. "There is a quote from her: 'I paint self-portraits because I'm alone so much and I know myself the best,' " says Aurore Giguet, Barrick's program director. "A lot of times, artists try to portray themselves in a better light, and she doesn't do that. She paints herself as she sees herself."

Pain underlines such pieces as the aforementioned "Wounded Deer" and "Henry Ford Hospital," picturing her in a Detroit hospital room after a miscarriage, her figure in bed, surrounded by elements including the fetus. Essentially wiping out her ability to have children, the bus crash was so traumatic that she could never bring herself to paint it, though its horror is depicted in a pencil sketch as she's on a Red Cross stretcher, trolley suspended above her.

Addressing her health hurdles further, the oil painting "The Broken Column" shows us Kahlo, breasts exposed, torso with a gash down the middle for the numerous operations on her spinal column, her body encased in a steel corset, nails in her body representing intense pain.

Life with Rivera -- and its contradictions -- are also evident in works such as "Double Portrait," created as a birthday gift to her husband, their faces melding into one to demonstrate the strength of their union, two halves of the whole. Yet "Without Hope" has her in bed surrounded by animals some observers think represent "The Hen," "The Turkey" and "The Pig" -- Kahlo's names for her husband's lovers.

Elsewhere in the exhibit is a piece inspired by the four years she and Rivera lived in the United States, a portrait of Kahlo straddling the border between America and Mexico. Desert flora and elements of Mexico's cultural past fill its side, while the U.S. portion depicts our obsession with industry and technology, brimming with skyscrapers and smokestacks spelling "F-O-R-D" belching gray clouds into an American flag above.

"She had a very unique style and managed to incorporate many elements of Hispanic culture into her paintings," says Luna, adding that despite her lasting troubles, she also embraced life, as evident in a simple still life of fruit, with a phrase etched into a watermelon slice: "Viva La Vida" ("Long Live Life"), completed eight days before her death.

Introspective insights flow through "Viva Frida," spotlighting an artist who turned her life into art that spoke for so many lives. As photographer Lola Alvarez Bravo said of Kahlo:

"Frida is the only artist who gave birth to herself."

Contact reporter Steve Bornfeld at sbornfeld@ reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0256.

Preview

"Viva Frida" exhibit

8 a.m.-4:45 p.m. Mondays-Fridays, 10 a.m.-2 p.m. Saturdays (through Dec. 10)

Marjorie Barrick Museum at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas,

4505 S. Maryland Parkway

Free; suggested contributions: $5 for adults, $2 for seniors (895-3381; barrickmuseum. unlv.edu)