History, music inspire center’s art for the masses

The sketch looks kind of like decorative sheet music, sound transcribed into color and then given shape.

The bright columns of various hues all have a musical note written beneath them, the width of the lines corresponding with the length of the note, whose pitch determines its shade.

The finished piece is mounted on the wall in an adjacent room of artist Tim Bavington's downtown Las Vegas studio, which is tucked away in an industrial area beneath U.S. Highway 95.

It's a striking painting, bold and conceptual, and it enlivens its workmanlike surroundings like a flower that's bloomed from a crack in a sidewalk.

It's one of two works that Bavington has created for The Smith Center for the Performing Arts, both of which are inspired by composer Aaron Copland's "Fanfare for the Common Man."

"The painting was based on the bass and treble lines of the music," Bavington explains, standing over the schematics for the piece, which are sprawled across a work table on a recent Thursday afternoon.

Music has long played a driving role in Bavington's art, and you can tell as much just by looking at him -- currently, he sports a black Sun Records T-shirt emblazoned with the image of the single for Elvis Presley's version of "I Forgot to Remember to Forget."

He selected "Fanfare for the Common Man" from a list of suggestions, ranging from Beethoven to Willie Nelson, supplied by Smith Center board members.

Thematically, the composition dovetails with one of The Smith Center's central aims, which is to make the arts accessible to a broad audience in egalitarian fashion.

Written in 1942, "Fanfare" also harks back to the era shortly after the construction of the Hoover Dam, which was a significant design motif in the building of The Smith Center.

Using the past as a springboard to the present figures prominently in Bavington's works as well.

"I can relate to what the architect did to the building," explains the England-born Bavington, who's lived in Las Vegas since 1993, "because when I started making these paintings back in the mid-'90s, I had a parallel sort of thought, where I was looking back 30-odd years to the '60s to color field painting and abstraction. I was looking back to an era that I felt was still relevant."

The challenge, then, is looking back while simultaneously moving forward, a balancing act that has come to serve as the fulcrum of Bavington's career.

With his Smith Center commissions, Bavington expanded his signature acrylic paintings to a new medium: sculpture, in the form of a massive, 80-foot-long installation piece that serves as the backdrop of the outdoor stage at Symphony Park.

The project is basically a Bavington painting in steel form, with lushly enameled tubes of various heights and widths.

"The difficulty was imagining how something like this might look at scale, because how can you imagine something that's never been seen?" wonders Bavington, noting that some of the metal pieces are close to 30 feet high. "I can't think of another work that's been made like this. It gives you a little more incentive to actually do it."

The tubes were fabricated in a shop in Los Angeles, as Bavington's studio, while spacious, isn't nearly big enough to house the mammoth project.

Just next door, at another work space in the complex, artist David Ryan is putting the finishing touches on a pair of large wall sculptures that will be displayed in the upper level of Reynolds Hall in The Smith Center complex.

Because of their large dimensions -- the pieces are around 7 feet by 8 feet -- it's difficult to get a feel for them on the ground level, so Ryan takes us to the second floor of his studio, where we look down at the elaborate, curved figures, their contours highlighted by gold leaf.

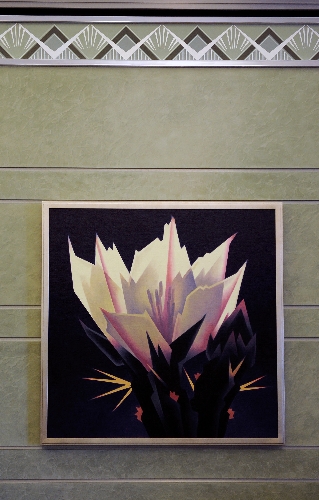

The pieces are both inspired by and something of a counterpoint to the art deco style that The Smith Center's design is posited upon.

Ryan, a nonrepresentational artist whose works are frequently characterized by irregular line work and asymmetrical patterns, isn't used to placing any bounds on his work, but for his Smith Center contributions, he did create within some parameters set by the board members.

"There were some good rules there that I could get behind and see what I could make of it," says Ryan, as "Suzie Safety" from Los Angeles popsters Sparks plays in the background. "It definitely inspired the look. It didn't feel like a limiting boundary. I found more freedom in it, so I kind of embraced it."

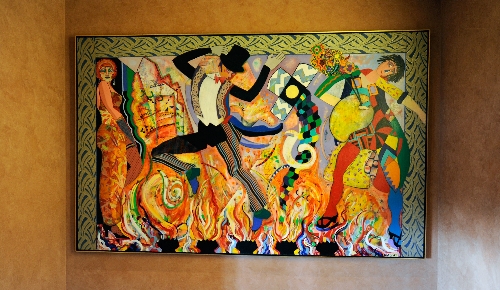

Ryan credits The Smith Center for seeking out locally based artists or those with ties to the city for much of the artwork, which also includes an installation piece from another Las Vegas artist, Shawn Hummel, as well as a contribution from renowned sculptor Benjamin Victor, who lived in Vegas for a time, beginning in the late '90s. (North Carolina's William Behrends, who created a bronze sculpture of Smith Center namesakes Fred and Mary Smith, as well as Western-themed painter Ed Mell also have works featured at The Smith Center.)

Victor's contribution is based on Oscar Hanson's "Winged" figures at the Hoover Dam, but rather than create a replica, he put the piece in motion, so to speak.

"The more I got into the study of it and what was going on at The Smith Center, I thought that it would be more meaningful if it had the essence of Oscar Hanson's work, but it was in flight to really capture that theme and concept of the performing arts at The Smith Center," Victor explains. "Of course, you have a lot of respect for an artist's work, but it almost shows more respect to do that sort of thing than to do an exact duplicate of their work."

The layout of The Smith Center itself also played a role in Victor's conceptualization of the piece, which can be found in the center of the Grand Lobby within Reynolds Hall.

It's a design posited on grand ambitions, and one could say the same of the art it catalyzed.

"That was huge," says Victor, who also created a bronze statue of former Las Vegas Mayor Oscar Goodman for The Smith Center. "When I walked in there for the first time, especially after the interior was done, it was just unbelievable. The materials they used are top notch, and just the way everything is set up with an uplifting feeling and the art deco theme to it really matches well. In most buildings you couldn't put a 16½-foot sculpture inside."

Contact reporter Jason Bracelin at

jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476.