Local teaching artists boost arts education

Forgive the alteration of an old expression:

Those who can, do. Those who can't, teach.

Those who can will, but why not teach, too?

Particularly for artists, those twin gigs are a win-win proposition that is often a lost opportunity.

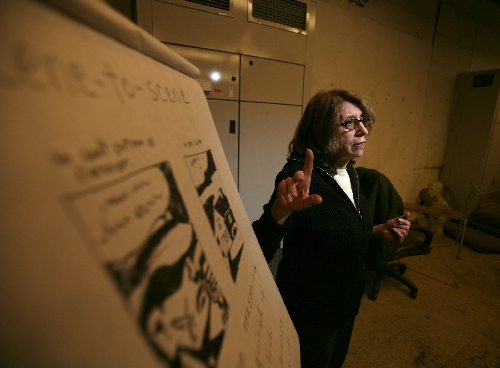

"Most of the artists I know don't teach," says Susanne Forestieri, an oil/acrylic/watercolor painter who doubles as an adjunct professor, teaching drawing to college students at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and to children at her home. "A lot of them came here during the boom years and they are all hanging on by a thread because they didn't go that route."

What a waste, financially, educationally and creatively -- a sentiment shared by the University of Chicago's Teaching Artist Research Project. Last year, the group released the results of a three-year study, concluding that artists heading up classrooms are an "underutilized resource" and "can be an important element of any strategy to reverse the long-term decline in arts education for American children."

Decline can be linked to lack of exposure and combated by the determination of working artists to usher the next generation into the artistic fold. That's clear when photographer Anita Getzler, a teacher of visual arts at Centennial High School, makes a disturbing estimation.

"At least 95 percent of my students had never been to an art museum and seen real paintings," says Getzler, who began an academic career as a museum educator around the same time she started exhibiting her photographs.

"I bring in that aspect so when students leave my class, they have skills for looking at art and talking about it, knowing the language of art."

Most artists, the Chicago study says, teach part time, earn about $10,000 annually from it and are eager for more, which would bolster numerous skills of their students.

"Learning in the arts is strongly correlated with improved student behavior, attendance, engagement in school, critical thinking, problem solving, creativity and social development," says Nick Rabin, the study's principal investigator, in the report. "The positive effects are most significant for low-income students."

Yet the quality of local arts education, even with some teaching artists, isn't held in high regard by one major arts figure in town. While praising Las Vegas Academy for providing "motivation," Arts Factory owner Wes Myles is less impressed with the execution. "The actual skill level is not up to national standards, in terms of what teachers are teaching," he says.

"They're doing the same damn thing I got taught in grade school: 'No, Johnny, a house doesn't look like that. No, Johnny, a house looks like this.' It's the same (expletive) with no real exposure to the art world. The big field trip is to go to the Bellagio. That's a lot better than nothing, but it's not the broad experience I've seen in other cities."

Benefits of teaching artists go both ways, says Las Vegan Brent Sommerhauser, a sculptor/3-D artist/printmaker who is a visiting lecturer at UNLV.

On one hand, students gain perspective from a genuine practitioner of the art. "I'm a sculptor myself, so I have actual experience making a lot of the same decisions I'm asking them to make," Sommerhauser says. "They come up with questions on things I'm going to grade them on, and I can say I've run into that problem myself and here's how I handled it, not just what I think the right answer should be."

Conversely, teaching can inspire the artist. During the first two weeks of school, Sommerhauser says he accomplished more in his studio than during a similar period during the break. "You go to (teach) and pay attention to the process and talk about it," he says. "You come home and turning on the TV is less appealing when you've mustered a genuine enthusiasm in front of 40 people. It kind of sticks around."

Still, like most teachers, artists often are stymied by budgetary restraints when they try to build on the expertise they can offer students by bringing in fellow artists as classroom guests.

"I have nothing to offer working artists in terms of compensation," Sommerhauser says. "When I taught in Detroit, we had a small budget where we could give someone $100 for making the trip. Here at UNLV, I suggest it every now and then but nothing has come of it."

Psychological benefits of artists as educators include getting them outside themselves emotionally. Though most do their work alone, getting out into the community can alleviate the overwhelming solitude for some.

"Some people are solitary enough that they don't crave other things, but I'm very outgoing for an artist," Forestieri says. "I can't be in my studio eight hours a day, I'd get miserable and depressed, and I couldn't do without the income."

Even so, Forestieri cautions that more than just extra greenbacks should motivate teaching artists. "I know (an artist) who teaches and she's all about keeping the room clean and getting the kids in and out in an orderly fashion," she says.

"There's no creativity or flexibility. It's deadening."

Ideal attitude? Sommerhauser nails it:

"I didn't want to teach in default mode," he says. "So many fall back on teaching when they can't find anything else to do. Teaching is something I choose to do."

He can do.

He teaches, too.

Contact reporter Steve Bornfeld at sbornfeld@review journal.com or 702-383-0256.