Nevada State Museum exhibit flows from earliest life to Rat Pack

Ratpackosaurus.

Sorry, no skeleton casts of Frank and Dino nursing a drink and a cig. Consider that shorthand, though, for the range of exhibits -- more or less the Mesozoic Era to the Ring-a-Ding-Ding-ozoic Era -- at the new, 70,000-square-foot Nevada State Museum up the hill from Springs Preserve, its sprawl making its old digs near Lorenzi Park look like a men's room.

The joint's jumpin' with history.

"This is a really great place, but it's more than that," says museum director David Millman. "It's part of Las Vegas maturing as a city. Soon you'll have the Smith Center, with the Neon Museum, the Mob Museum downtown. It's not just culturally and educationally important, but it's one more piece of bringing Las Vegas back to where it was economically, and certainly a step ahead culturally."

Through the front door, to the side of the twisty facsimile of a bristlecone pine, the state tree, awaits the museum store -- gotta peddle the merchandise -- plus an educational center for school groups, research library and special events facility before you enter the hallway offering two destinations: the permanent exhibit hall and the changing exhibit space. (That area currently hosts "Unexpected Nevada" featuring the sharp, crystalline photos of Cameron Grant, into April. Then exhibits change every three months.)

Outside the permanent exhibit, examine the "Desert Love Buggy" (imagine makin' out in this contraption at the drive-in), the 1911 Sears Model K obtained in 1939 for the Helldorado Parade, motoring around till 1994. Also, a display case titled "Gone But Not Forgotten" sets a Vegas mood with a $25,000 Dunes gambling chip and postcards from iconic hotels, including the Sands (Red Skelton on the marquee), Stardust ("Lido de Paris" on the marquee), Thunderbird and Last Frontier.

Inside? Nevada, from soup (prehistoric life) to nuts (Howard Hughes) and beyond. With exhibit-specific sound effects, the layout is stuffed with informative panels, posters, models, illustrations, photos, artifacts, fossils, skeletons, re-created railway and mining outposts, 3-D films and sections on the rise of Reno and of Vegas' development into the Entertainment Capital of the World, with footage that is, in the era's lingo, a gas, baby.

Hey, big boy -- and we're talkin' BIG at about 13 feet high: That's the skeleton cast of the Columbian mammoth, an elephant that roamed Vegas between 10,000 and 60,000 years ago (making it our first major headliner). The creature weighed about 11 tons, and the remains of its tusk, teeth and lower jaw were retrieved from Price, Utah.

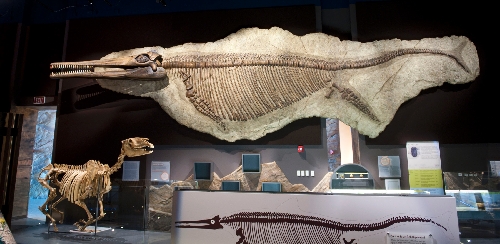

Modest by comparison are species including the Shasta ground sloth (posed in attack mode), which lived in Nevada for several million years until the end of the last Ice Age, and the reptilian ichthyosaur, a marine predator from the Triassic period, 225 million years back. Low-tech but fun, a sliding magnifier enables visitors to closely inspect wall-mounted fossils.

"The Desert Does Its Best Talking at Night," reads a quote from travel writer William Least Heat-Moon, tying together exhibits brimming with models of cougars, lizards, a gray fox, bighorn sheep and coyote, among others, set against the projection of a warm, purply desert dusk behind a scrim. Flora and fauna and the landscapes of the Mojave and Great Basin deserts feature plants and insect life, while a rock tunnel teaches about limestone, sandstone and volcanic rock.

Large, lit panels offer portraits and tidbits on numerous influential Nevadans, including John C. Fremont (whose account of his campout at Las Vegas Springs was the first published record of Las Vegas), opera singer Emma Nevada (who adopted her state's name before becoming a warbling phenom in Europe), and Yale geology professor Chester Longwell (who mapped much of Southern Nevada).

Exhibits examine Nevada's first Native Americans and European settlers, aided by film portraits of Washoe tribe members, as well as Wovoka, the Northern Pauite religious leader who founded the Ghost Dance spiritual movement.

Near a covered wagon, read about the direction-impaired Donner party that, pre-GPS, strayed into Sierra Nevada during the wrong time of year with calamitous results. As quoted by 13-year-old survivor Virginia Reed: "Take no shortcuts, and hurry along fast as you can."

Railroad construction is copiously chronicled. Included: the re-creation of water towers circa 1860, the front of a railway depot, a people-powered railway cart (featured in every other movie Western, seesawing down the tracks) and the Comstock Mine, where building began on the world's "crookedest railroad" connecting to Carson City, Virginia City, Gold Hill, Silver City and Reno. Within, see 3-D films with actors as miners and the mine owner.

Eclectic memorabilia runs from a Mark Twain letter to photos of Reno after its 1868 founding to 1950s downtown, to a picture of Mary Pickford, whose scandalous 1920 divorce helped launch our "divorce industry." Further sections include film on Hoover Dam and nuclear testing, Nevada's military complex and the segregation of African-Americans before the "Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas" sign ushers visitors into a historical cornucopia of Vegas entertainment.

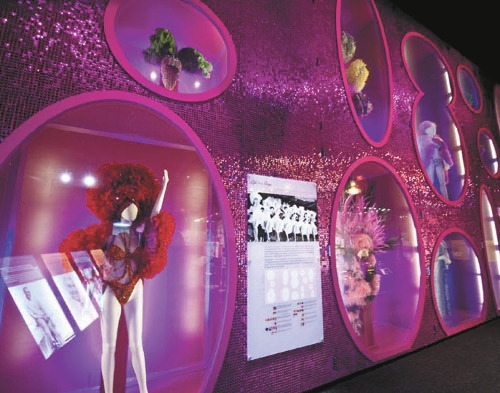

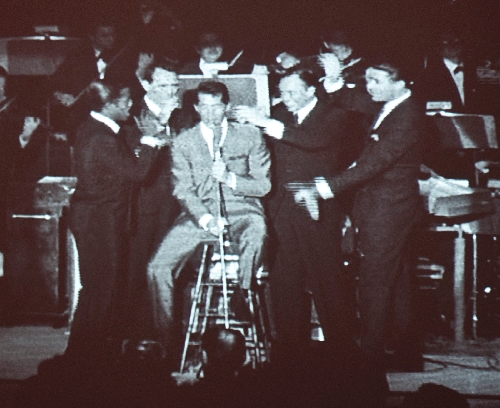

Spotlights crisscross above Rat Pack footage -- yes, that's Sammy and Peter Lawford executing some wiggy dance moves -- that leads into a montage of celebs, including Robert Goulet, a golfing Bing Crosby, Dinah Shore and Elvis, and a spangly back wall shows off glitzy showgirl costumes. Display cases feature swingin' Vegas artifacts, from an Alfred E. Neuman slot machine to hotel knickknacks. Panels tell of the moguls, highlighted by Howard Hughes and Steve Wynn. Don't call them fossils.

Still, in some future century, perhaps they'll add the Hughesosauros and Wynnosaurus Rex exhibits.

Contact reporter Steve Bornfeld at sbornfeld@review journal.com or 702-383-0256.

Preview

What: Nevada State Museum at Springs Preserve

When: 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Friday-Monday starting Friday

Where: 309 S. Valley View Blvd.

Admission: Free with $9.95 adult admission to Springs Preserve; free for children 17 and under (486-5205;

museums.nevada culture.org)