UNLV museum exhibit dedicated to proposed Avi Kwa Ame National Monument

‘There’s been no lack of excitement, no shortage of people wanting to be involved,” artist Mikayla Whitmore says of “Spirit of the Land,” a recently opened group exhibit she helped curate that runs through July 23 in UNLV’s Barrick Museum. (There will be a concurrent exhibit in the Searchlight Community Center.)

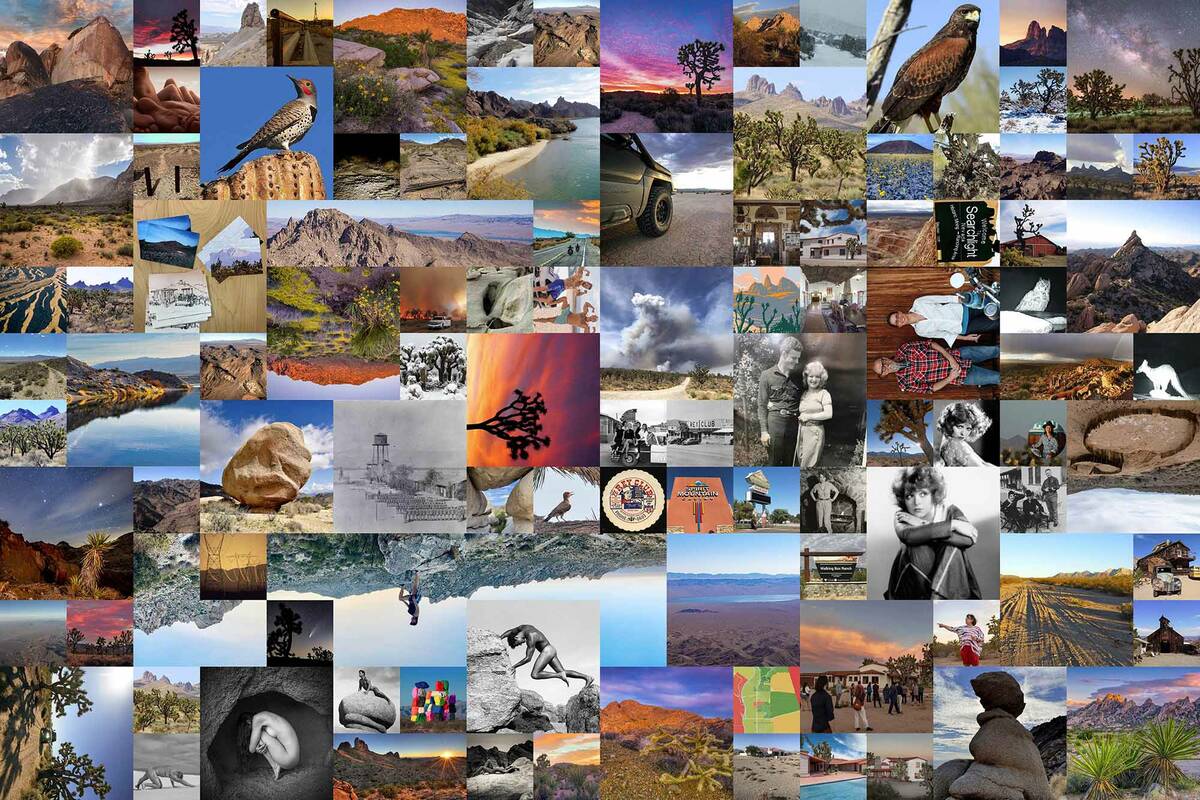

And no wonder: “Spirit of the Land” celebrates the 450,000-acre region near Searchlight known as Spirit Mountain that’s now being considered for federal protection as Avi Kwa Ame National Monument. Precisely the sort of confluence of issues — preservation of Indigenous cultural sites, environmental well-being, the deep beauty of the desert — that many artists can be counted on to rally around.

“One look at the lands is all that’s needed to understand why this landscape is being proposed to become the new Avi Kwa Ame National Monument,” wrote Kim Garrison Means, another co-curator, in a commentary published last month in the Las Vegas Review-Journal. (Artist Checko Salgado was a third curator.) She elaborates in a news release for “Spirit of the Land”:

“One of the misconceptions we are hoping to address with this exhibition is the idea that the desert is a wasteland, and therefore a place to be exploited as we wish.”

Some 40-plus artists were invited into the show, many of them familiar to Las Vegas art aficionados — Adriana Chavez, Sam Davis, Natalie Delgado, Justin Favela, Julian Kilker, Sierra Slentz, Lance L. Smith — as well as Indigenous artists and national ones, too. They had to have or make a connection with the area, either already working in a desert-centric mode or be willing to venture out to the Avi Kwa Ame area, Whitmore says. Means owns a ranch there, called Mystery Ranch, which often hosts artists, scientists and others who wish to study the biome.

“Number 1,” Whitmore says of choosing the participating artists, “we wanted to get a breadth of voices, histories and experiences” — not to mention styles and techniques. Included are photographers, painters, assemblage artists and sculptors, working in modes ranging from documentary realism to pure abstraction.

Painter Nancy Good, for example, feels a deep inspirational connection to the region — “I love interpreting the beauty of the desert,” she says — but you’d be hard-pressed to describe her colorful abstracts as “landscape art” in any but the loosest sense.

But when it came to participating in “Spirit of the Land,” the first word of the exhibit title proved to be her ideal portal into the concept. She arrayed the biomorphic shapes and meticulous dot-work that have long marked her paintings around the idea expressed in her piece’s title — “Mojave Spirit Dreaming” — to ask: “What would the desert’s spirit dream of?” Natural histories, surely, and infinite biologies, from macro to micro, and the continuities of life and death in the starkly beautiful landscape. “All that has been created here and died here continues to contribute to the dream of its spirit,” she says.

To her standard vocabulary, Good added a new element of sharp-edged realism by using a skeletal piece of dead cholla as an airbrush stencil to add a startlingly lifelike texture. So as you view the piece, you move back and forth between the cholla and the dots, which allude to nature’s tiniest life forms, with the patches of fluorescent color reminding you of the desert’s persistent lichens.

It all adds up, Good says, to a “visual ballad,” a love song “to the microscopic primordial beginnings of the beautiful and mysterious Mojave desert, to the larger life and death stages of our sacred natural spaces.” Even the repeated use of the cholla stencil is intended to layer on more meaning: “Repetition is important in our storytelling,” she says, “in how we cement our identity.”

It may be that the sublime vastness of a desert — easy enough to dismiss as “empty” if you’re not familiar with its natural and Indigenous histories — triggers an impulse among some people to imprint their presence on the land. You see it in the destructive off-roading, in the trash strewn everywhere — and, if the land in question happens to have a name like Christmas Tree Pass, you see it in a more festive, if no less destructive way: holiday ornamentation draped on Joshua trees.

“People decorating trees,” says Whitmore, a photographer, with a sigh, “not thinking about the environmental ramifications” — because you know those people don’t come back to retrieve their ornaments — “or that this is a sacred space for tribes.” It’s a seasonal affliction at Christmas Tree Pass, the main route up to Spirit Mountain, and is a dispiriting sight, the trees swaddled in the celebratory fervor of America’s premier consumer blowout. “The strangeness of it is striking,” she says.

So Whitmore’s contribution to “Spirit of the Land” is a pair of 20-by-30-inch photographs. The first documents a Joshua tree from Christmas Tree Pass “suffocating in garland and tinsel,” as she puts it. The second shows the same tree a month after she and others removed 10 garbage bags worth of merry and bright debris and surrounding litter. (It may, Whitmore suggests, be time to rename the pass, to something that doesn’t promote festive desecration or celebrate counter-Indigenous tradition.) The dual images underline the unintended consequences of our intrusions into delicate landscapes — how even a well-meaning gesture has destructive implications we need to think through.

Back to those bags of recovered ornamentation: For the installation of “Spirit of the Land,” Whitmore and fellow artists fashioned some of the garland and tinsel into a silhouette of Spirit Mountain, in hopes of creating an “educational moment.”

An educational moment is what Fawn Douglas, a Southern Paiute artist and activist, hopes the exhibit itself will be, especially as it’s placed at UNLV where college-age people can see it, learn from it and perhaps be inspired, as she is.

A sense of place is important to Douglas “I couldn’t produce art if I didn’t touch that sand, put my feet on it, sit and listen to the desert and hike around in it,” she says. “I had to physically be there to absorb it.”

That deep grasp of the region shows up in her contribution to “Spirit of the Land.” In her painting, watercolor washes of sandy browns, pinks and purples tease out the desert’s colors, while four blue ribbons cascade vertically down its face, alluding to water: “How scarce it is,” she says, “how needed it is, the beauty it brings.”

This is more than just the blatant hydrological reality of the desert. It connects to her heritage: She notes that the word Paiute means “people of the water”: “People in search of water,” she says. “People of the desert.” (But not the only people of the desert; she used the ribbons in her piece vertically in deference to the horizontal weaving tradition of the nearby Fort Mojave tribe. Indeed, she says, the Avi Kwa Ame area has been an “area of travel” for a number of Indigenous peoples.)

The effort to establish Avi Kwa Ame as the state’s fourth national monument has taken place on several fronts — political (the bill calling for monument status was introduced by Nevada Congresswoman Dina Titus this year), social (Garrison and other proponents have held numerous community discussions on the proposal) and environmental.

But this artistic front is as important as the others, Douglas says. “It’s what people remember,” she says. “It’s the art that tells the story of these times.”

Preview

What: "Spirit of the Land" art exhibit

When: July 23

Where: UNLV's Barrick Museum

Opening reception: 5-8 p.m. Friday, with remarks at 6:30 p.m.

Info: unlv.edu/barrickmuseum