‘Warhol Out West’ exhibit at Bellagio features dozens of artist’s works

In his lifetime, Andy Warhol was hardly a Vegas kind of guy.

According to those at the Andy Warhol Museum (located in Warhol’s hometown, Pittsburgh), Warhol visited Las Vegas just once.

That was in 1963, on his way to — or from — a show at the Los Angeles gallery that gave him his first solo exhibition. (Warhol reportedly used artist Marcel Duchamp’s roulette strategy to win some money for gallery owner Walter Hopps.)

Almost 26 years after his death, however, Warhol’s back in Vegas — in a big way.

“Warhol Out West,” opening today at the Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art, showcases 59 of the legendary pop artist’s works.

From paintings to wallpaper, from photographs to sculptures, “Warhol Out West” reflects his fascination with, and connection to, the power of imagery, whether depicting a gun-toting Elvis Presley (“Double Elvis”) or a multihued “Dollar Sign” — both of which qualify as very Vegas indeed.

That’s why Las Vegas makes an ideal setting for “Warhol Out West,” according to Eric Shiner , director of The Andy Warhol Museum, which is partnering on the show with the Bellagio gallery.

“Vegas was just a natural fit,” Shiner says, adding that “Andy would be thrilled to know” his artworks were going on display “down the street from Celine Dion.”

After all, Las Vegas ranks as “the epicenter of pop culture,” he notes. “It’s glitzy, glamorous — and a little bit seedy,” a mix of “high and low culture. Warhol loved those things.”

Warhol also “saw no line between art and commerce,” Shiner says, so “we’re quite excited to be doing (the show) within a casino complex.”

And Bellagio gallery officials are equally excited about welcoming the all-Warhol exhibit.

“Even though Warhol has been dead for more than 20 years, his work is more significant than ever,” says Tarissa Tiberti, the Bellagio gallery’s executive director.

From Warhol’s prescient 1968 prediction that “in the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes” (presaging a YouTubed, reality-TV world) to his continued star status on the auction circuit, the artist, and his art, are “more significant than ever,” in Tiberti’s view.

“Artists are looking at him for inspiration,” she says.

Moreover, Warhol’s work remains “fresh today — it’s not dated. It’s kind of reinventing itself continuously,” she says, enabling Warhol’s work to “transcend time.”

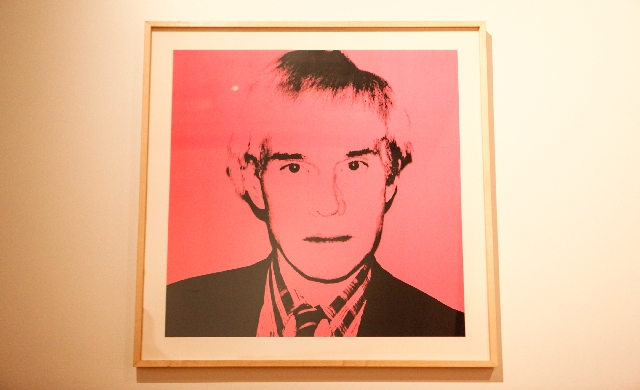

And though “the man is always closely associated with his artwork,” in part “because of the huge mythology he built around himself,” Shiner says, “the work stands on its own.”

Yet even those who have no knowledge of (or interest in) Warhol’s work can’t help but recognize, and respond to, his images.

Elvis, Elizabeth Taylor and Dolly Parton — whose portraits all turn up in the Bellagio show — are “famous in their own right,” Tiberti points out.

The way Warhol reimagines instantly recognizable nonhuman images — from the symbolic dollar sign to one of his signature Campbell’s Soup cans — encourages viewers to reconsider objects they may take for granted, she adds.

Bellagio gallery officials approached The Warhol Museum more than a year ago with the idea for “Warhol Out West.”

The Warhol Museum receives, on average, about five requests a week from other institutions interested in presenting the artist’s work, Shiner says. (Since 1996, more than 9 million people in 36 countries have seen Warhol shows organized or co-organized by the museum.)

“We do attempt to focus on new areas where Warhol hasn’t been shown,” he says. So “Vegas was just a natural fit.”

Some of the “Warhol Out West” works reflect Las Vegas’ trademark dazzle, Tiberti says, including “Diamond Dust Shoes,” with its neon-rainbow pile of high heels.

And “Double Elvis” — which debuted at the 1963 Los Angeles gallery show that also prompted Warhol’s one-and-only Vegas visit — doesn’t leave the museum building that often, Shiner says, because of its fragile nature.

“Andy used really, really bad silver paint, industrial paint” on the canvas, he says. “It does not age very well,” so “we do have to be extremely careful.”

(Warhol made 22 versions of “Double Elvis,” which shows Presley as he appeared in the 1960 Western “Flaming Star.” Nine of the paintings are in museums; another version sold last year at auction for more than $37 million.)

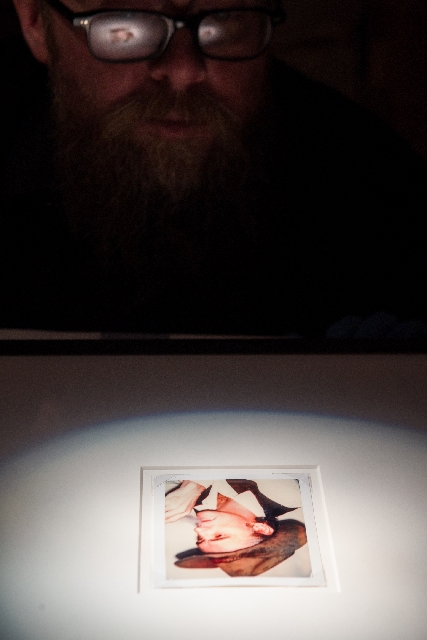

In addition to paintings, including Warhol self-portraits, “Warhol Out West” features everything from yellow and blue cow-patterned wallpaper to Polaroid photos, screen-test footage and the floating Mylar pillows of “Silver Clouds.”

Warhol was so prolific that the show could “link him to anything prior to ’87,” the year he died, Shiner says.

But some “Warhol Out West” works have a more direct connection to the exhibit title — including the paintings in Warhol’s 1986 “Cowboys and Indians” suite, which features depictions of such Western icons as Geronimo, John Wayne, Annie Oakley — and a buffalo nickel.

Despite their frontier focus, “Warhol would immediately say he didn’t care about the real thing,” Shiner says. “It’s all about the surface, the facade.”

And what could possibly be more Vegas than that?

Contact reporter Carol Cling at ccling@

reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0272.

Preview

"Warhol Out West"

10 a.m. to 8 p.m. daily (last admission 7:30 p.m.) through Oct. 27

Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art, 3600 Las Vegas Blvd. South

$11-$16 (693-7871, www.bellagio.com)