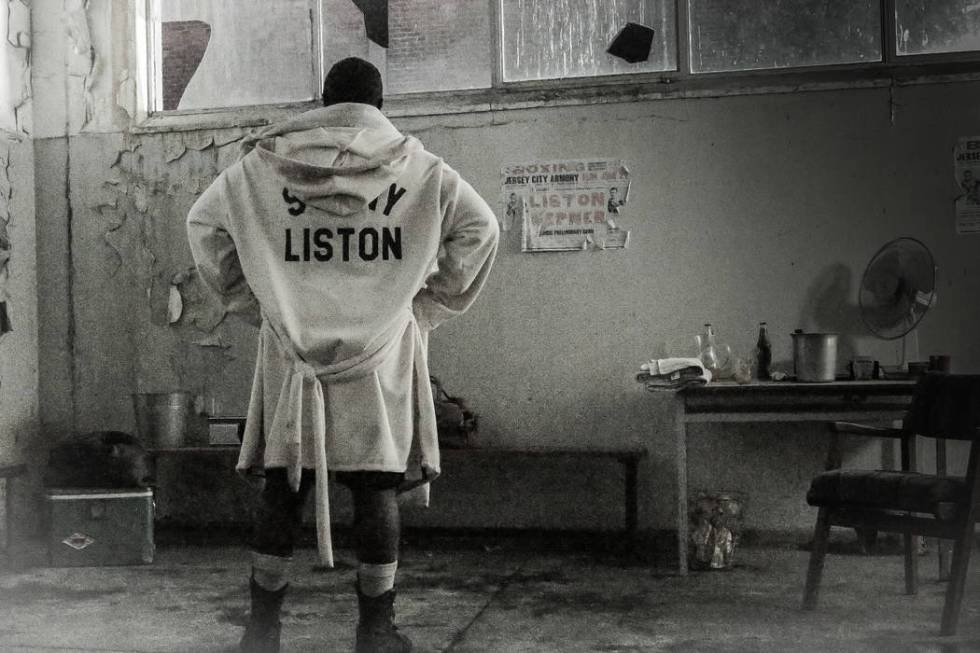

Sonny Liston’s stunning Las Vegas demise explored in new documentary

There’s no record of his birth and no clear account of his death.

“He was a mystery right from the start,” Nigel Collins, ESPN boxing columnist and former editor-in-chief of The Ring Magazine, says in “Pariah: The Lives and Deaths of Sonny Liston” (9 p.m. Nov. 15, Showtime).

In the course of a little more than eight years, Liston went from capturing Floyd Patterson’s heavyweight title with a first-round knockout in Chicago’s Comiskey Park to allegedly selling heroin on Las Vegas’ Westside and dying of a presumed overdose — one that’s still believed by many to have been an act of murder — at his home on Ottawa Drive.

Fighting for his life

His demise was nearly as stunning as his rise.

Born somewhere around 1930 — even he wasn’t sure when — as the 24th of Arkansas sharecropper Tobe Liston’s 25 children, the man whose given name was Charles endured regular whippings that scarred his back and was made to work the fields by age 8.

In 1950, after following his mother to St. Louis, he was convicted of armed robbery and sentenced to prison, where he learned to box — when he wasn’t fighting for his life.

Paroled just two years into a five-year stretch, he turned pro in 1953, with mobsters including John Vitale, Frankie Carbo and Frank “Blinky” Palermo controlling his contract. By the time he’d lost the title to Cassius Clay in 1964 as well as the rematch in his opponent’s first fight under the name Muhammad Ali — both of those defeats coming under mysterious, rumored-to-have-been-fixed circumstances — Las Vegas seemed the perfect city for Liston.

“It was a marriage made in heaven,” author Shaun Assael says in “Pariah.” His book “The Murder of Sonny Liston: Las Vegas, Heroin and Heavyweights” serves as the basis for the twisty documentary that plays out like a piece of pulp fiction.

“Sonny never walked on well-lit streets. Sonny moved around in darkness,” Purdue University history professor Randy Roberts says in the film.

‘Sonny could pull it off’

And you can’t talk about a brutal, terrifying fighter without checking in with longtime Las Vegan Mike Tyson.

“Sonny Liston had a big, menacing, tough-guy reputation, and that superseded him in the ring,” he says. “He intimidates the fighter, the fighter’s really beaten before he got in the ring. Sonny could pull it off. I could pull it off. Not a lot of people could pull it off.”

Liston’s final professional highlight — his first-round dismantling of Patterson in their July 22, 1963, rematch — was in Las Vegas, but his association with the city was mostly downhill after that.

He lived with his wife, Geraldine, at what is now Las Vegas National Golf Club, near Desert Inn and Eastern. But, according to the documentary, he was more comfortable on the Westside.

“Every morning he would go to Friendly Liquor Store (on H Street) and buy two bottles of wine to start his day out,” says former narcotics detective Larry Gandy. “We’d had 16 murders in one year in that one bar alone.”

A ‘terrible’ way to go

Gandy is also the source of the lurid description of Liston’s body, found at his home on Jan. 5, 1971, when Geraldine returned from a trip.

“It didn’t even look like Liston, he’d been dead for so long. He’d been dead four or five days,” Gandy says in the opening moments. “He was bloated. He was full of methane gas. It really made me sick to my stomach because he was such a predominant figure in (the) sports world. I just thought it was a terrible, disrespectful way for him to go.”

After his death, which was ruled to have been from natural causes, friends would say Liston was terrified of needles and would never have shot heroin.

According to “Pariah,” there was a gap of several hours between when Geraldine found Liston’s body and alerted the authorities. There are tales of local drug dealers with grudges, real and perceived, as well as allegations of the mob’s involvement and some truly out-of-the-blue suspects.

In the end, “Pariah” insinuates, it wasn’t so much a matter of who would want the former heavyweight champion dead as it was a case of who didn’t.

Contact Christopher Lawrence at clawrence@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4567. Follow @life_onthecouch on Twitter.