Ticket price ‘bait-and-switch’ gives fans no satisfaction

It was one of those emails generated by frustration as much as keystrokes.

It was a familiar complaint, one we’ve heard many times before — and experienced firsthand.

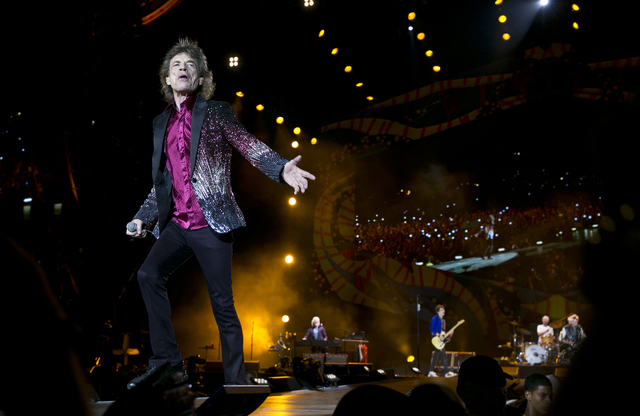

Recently, Rolling Stones fan Lorraine McIntrye was hoping to score tickets to their Oct. 22 show, the second of two nights the band will play at T-Mobile Arena, which went on sale at 10 a.m. on a Friday a few weeks back.

She attempted to purchase tickets online right when they became available.

“By 10:05 a.m. all lower price tickets were sold out,” McIntrye wrote to us via email shortly after failing to score her desired seats. “How can this happen in five minutes? Now these same tickets are being sold on resale sites. The Stones have fans that can’t see the show because of an unfair allocation.”

Numerous readers have shared similar experiences in recent years: You go to buy tickets the minute they go on sale, only to discover that many, if not all, of the best seats have immediately been kicked to resale sites such as TicketsNow, which is owned and operated by Ticketmaster, where they are substantially more expensive.

“It’s very disappointing,” McIntrye wrote. “Similar to bait-and-switch at car lots. Tickets are advertised for sale at one price, only to find out there are none available on day of sale unless you buy from a resale site at a higher price. I am no longer a fan of Rolling Stones if they condone this behavior.”

They certainly do condone this behavior, and profit from it.

The question becomes, then, is this fair?

Are the Stones, and plenty of other artists of their ilk, simply greedily soaking their fans?

Or are they making sure they’re getting their just share of what people are willing to pay to see a show?

Of course, the immediate impulse is to the answer first question affirmatively while shaking your fist at your Stones records and wondering aloud if Jagger’s next kid, due in the spring of 2017, will be doing his or her business in gilded Pampers.

But let’s calm down and try to understand the artist’s position here.

With physical album sales down, bands naturally need to maximize tour income to make up for the lost revenue, which is one of the reasons why concert tickets as a whole have become more expensive — ticket prices for the first six months of the year are up another 4 percent from the same time period in 2015, for an average cost of $46.69, which is a staggering 43 percent higher than they were in 2013, according to concert industry trade publication Pollstar.

What’s more, artists are also attempting to reap the proceeds of the secondary ticket market, which has grown increasingly lucrative, though it’s only in recent years that artists have started demanding their cut of this especially rich pie.

Let’s look at how things went in the past.

Say the Stones are coming to town — assuming Jagger could be convinced to take a little time off from siring more offspring — and all tickets for the first 10 rows carry a face value of $350.

In the past, some fans might be able to score those seats at that price, but, in a more likely scenario, so could ticket brokers who use both paid surrogates and “bot” software to give them a leg up on other potential buyers, and this only if they don’t have deals with various venues and promoters that allow them access to tickets that the general public doesn’t have.

The scalpers then flip those tickets for much higher prices, depending on demand.

With an act as iconic as the Stones, maybe they could double their money and sell the tickets at $700 a pop — that’s a $350 markup, and the Stones wouldn’t see any of those proceeds.

This is at the crux of the artist’s side of this argument: Why should anyone profit from a ticket to one of their shows but the band, promoter and ticket agency?

To this end, artists now participate in the secondary ticket market directly, offering the best seats immediately to resale sites and charging the highest prices that fans are willing to pay without ever giving anyone a shot at purchasing said tickets at face value.

The goal here is to beat scalpers at their own game and keep the money in-house.

Now, let’s apply all this to the previous example.

By selling those “$350” tickets immediately on a site like TicketsNow at a substantially higher price — let’s stick with $700 — scalpers aren’t eliminated completely, but it’s going be hard for a would-be reseller to justify paying $700 for a ticket in hopes of somehow flipping it for even more money, because the $700 is more reflective of the ticket’s true market price.

This is an important point to keep in mind: A ticket isn’t overpriced if someone is willing to pay said price.

In fact, it’s the opposite: If a ticket has a face value of $350 and someone will pay double that, then by definition, it’s underpriced.

Fans don’t want to hear that, but this is often the case, and it’s why the secondary market not only exists, but has become a $5 billion industry: Because the most desired tickets frequently cost less than they should in relation to the demand for them, which is what allows a scalper to pay face value and then resell for a substantial profit.

So, if so much money is there to be made on top of a ticket’s base price, shouldn’t artists benefit?

This being said, bands could be more upfront about the true cost of the best seats in the house. Advertising one price knowing that the choice seats aren’t really available at that cost is needless window dressing that only makes fans like McIntrye understandably upset.

Whether we like it or not, the reality is that the best seats at the most in-demand shows have become luxury items, the concert-going equivalent of Rolexes, Lamborghinis and flying in a private jet.

So, when it comes to going to a show, why do we still expect a Porsche for the price of a Prius?

Look, driving a Nissan Altima, sporting a Timex and sitting in the upper bowl at a Stones gig aren’t all that bad — even if they have all pretty much become one in the same.

Read more from Jason Bracelin at reviewjournal.com. Contact him at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com and follow @JasonBracelin on Twitter.