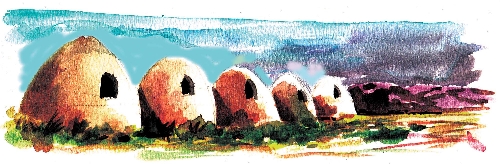

Charcoal ovens rekindle Nevada’s mining history

Beehive-shaped monuments to Nevada's mining past are scattered across the Silver State, often in remote canyons nearly hidden by trees and brush. Used to turn wood into charcoal to fire smelters in mining areas, the unusual conical ovens built of stone or brick were common in Nevada in the late 1800s.

Most measured 30 feet tall and 27 feet wide at their base with 2-foot walls. Each held 35 cords of wood at a time. Burning consistently, the charcoal ovens, or kilns, consumed whole forests of pinyon and juniper, denuding mountains of central and eastern Nevada.

The only site in the state where the structures are protected is in Ward Charcoal Ovens State Historical Park, where six complete ovens still smell of the resinous wood once burned there. The park is 18 miles south of Ely off U.S. Highway 93, about 220 miles from Las Vegas.

Visitors approaching from Las Vegas should watch for a marked turnoff 13 miles north of the junction of U.S. Highway 93 and U.S. Highway 6/50 at Major's Place. A graded road runs five miles from U.S. 93 to the park. If you are coming from Ely, drive south on U.S. 93 seven miles to the park turnoff, then 11 miles on a gravel road to the ovens. From their location at about 7,000 feet elevation, they command sweeping views of valleys and mountains, including imposing Wheeler Peak in nearby Great Basin National Park.

Constructed in 1876 of stone quarried in the area, the ovens provided charcoal to smelters in the neighboring Ward Mining District, where silver was discovered in 1872. The ovens were in constant use until 1879, when declining ore quality and diminished forest close at hand combined to close down activity.

The ovens became places where stockmen could take shelter during inclement weather. Stories tell of ovens also being used by bandits preying on stagecoaches and other traffic on the nearby road between Ely and Pioche. For decades, the ovens' location on private ranch lands protected the structures from vandals.

In 1956, a special-use permit allowed the state to open the ovens to the public. Nevada acquired the land in 1968, and the following year, the Legislature named the site a state monument. State park status came in 1994.

Park fees include an entrance charge of $5 for Nevada residents or $7 for nonresidents and camping fees of $12 for Nevadans or $14 for others.

The park is open year-round with two picnic areas, a campground with two large pull-through RV sites and a dozen family campsites and group facilities, including a large yurt. Restrooms are centrally located. Water is available during frost-free months. Reserve group sites at 775-289-1693.

Nearby Willow Creek attracts trout anglers. Developed trails challenge hikers and mountain bikers. An all-terrain vehicle trail connects to a network of off-highway routes on adjacent Bureau of Land Management lands. In winter, snowy trails in the park invite visitors to try cross-country skiing and snowshoe trekking.

While the park's ovens are preserved and protected, most of Nevada's dozens of old kilns suffer the effects of time, weather and vandals. Only collapsed bricks or stones mark the spots where many charcoal ovens once stood, while returning forests conceal others.

Accessible sites in the southern portion of the state include one reconstructed oven and ruins along Wheeler Pass Road from Pahrump, a site northeast of Panaca and another near Bristol Wells north of Pioche.

The skills once required to build the kilns are probably lost today. Swiss-Italian craftsmen brought their old skills to a new country, where they were in high demand for a time. An industry grew to feed charcoal to the insatiable smelters. Camps of woodcutters clear-cut forested areas and trimmed the logs. Others hauled wood to the furnaces. It took skill to stack the wood properly in towering levels with a chimney in the center. Properly vented, it burned for days, producing about 1,750 bushels of charcoal, for which the "carbonari" received a paltry sum.

Nevada's 1879 Fish Creek War was a rebellion over mine owners cutting the price (30 cents per bushel) they were paying. Although short-lived, the fight resulted in loss of life and a brief takeover of the mining boomtown Eureka.

Margo Bartlett Pesek's Trip of the Week column appears on Sundays.