Hovenweep National Monument makes a fine fall getaway

Typically balmy autumn days in the Southwest invite vacationing Southern Nevadans to explore scenic and historic regions such as the Four Corners area of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah. Among the many treasures of the past preserved in state and national parks and monuments in that region, hautingly beautiful Hovenweep National Monument stands out.

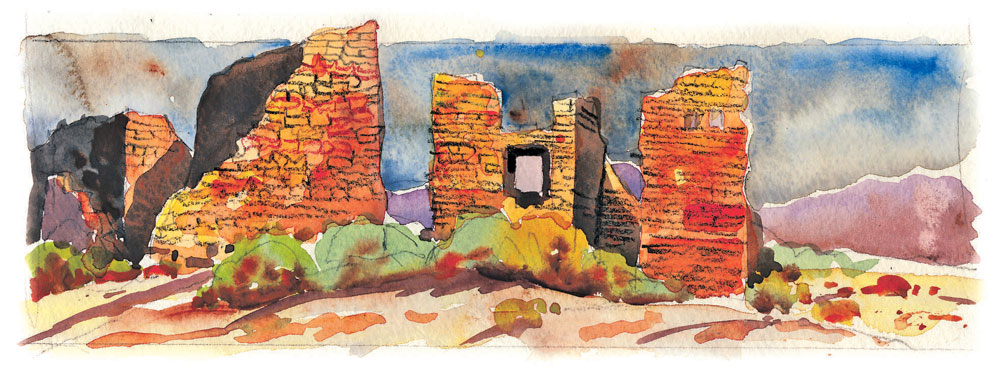

Characterized by exquisitely constructed towers, Hovenweep protects six related ruins on the border of Utah and Colorado. Part of the widespread Anasazi or Ancestral Puebloan culture, the ruins once housed 2,500 people. Stabilized but unreconstructed, the ruins today appear much as they did in 1854 when Mormon settlers discovered them nearly 700 years after they were abandoned. They acquired the name Hovenweep from a Paiute/Ute word for "deserted valley."

Hovenweep lies about 500 miles from Las Vegas between Cortez, Colo., and Blanding, Utah. Access side roads to the national monument from Highway 163 or Highway 160 across the Navajo and Southern Ute Reservations heading to Cortez or Blanding.

The main access road from three miles south of Cortez off Highway 160 follows the McElmo Canyon Road 40 miles to park headquarters at the Square Tower group of ruins. The scenic route along McElmo Creek passes well-watered farm lands, several pioneer-era dwellings, a one-room schoolhouse and an old trading post. This all-weather route provides year-round access, while other roads connecting more ruins and other highways north and west may be treacherous in bad weather. Inquire at the visitor center before exploring the other ruins spread over more than 20 miles of mesa and adjoining canyons. Short, uneven trails reach ruins at five other sites.

Facilities clustered at Square Tower include park services offices, a visitor center, a 30-unit campground and a 1.5-mile trail to the ruins, partially wheelchair accessible. From October to April, the monument remains open daily from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., except on Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year's Day. Hours are longer from April through September. Expect to pay a $6 per car entrance fee good for seven days. Tent and TV sites in the campground cost $10 per night, available on a first-come basis without reservations. Visitors preferring not to camp often stay in Cortez.

People of prehistory started hunting and foraging for native foods in the region about 10,000 years ago, moving seasonally. Eventually, the nomads took up farming to augment their seasonal gleanings. They learned to exploit the water sources of the region and the deep, rich soil of the mesas to raise small patches of corn, beans and squash. They enhanced the water by building small dams above springs to hold runoff. They toiled to save the soil from erosion with retaining walls. By 900 A.D., small villages grew up near the water and arable areas at different elevations for an extended harvest. The farmers built granaries in the cliffs for storage and traded their excess for other needed goods with villages linked by trails across the width of the Anasazi region from Southern Colorado to Southern Nevada.

The quality of the architecture sets Hovenweep's ruins apart from other Anasazi settlements. Constructed during the last and most advanced century of occupation, the Hovenweep ruins demonstrate architectural diversity and technical skill. The people built multiple-storied towers, cliff dwellings and clustered apartment-style structures, often of meticulously shaped and fitted stones without mortar. Bedded on basic stone, the square or round towers fit the natural curvatures. Orientation of some of the structures indicate the importance of solstices, equinoxes and other yearly events in the culture. Nearly all the Hovenweep ruins contain astronomical indicators.

The Anasazi people abandoned their villages across the region by the end of the 1200s, perhaps because of a prolonged period of drought. Many experts think they headed south to become the ancestors of today's Pueblo, Hopi and Zuni people.

Margo Bartlett Pesek's column appears on Sundays.