Computer animation draws families into theaters with clever stories

In the annals of animation, 1986 was hardly a banner year.

While "Top Gun" flew past " 'Crocodile' Dundee" to take the top box-office spot, two lively little mice -- "An American Tail's" Fievel and Basil of Baker Street, alias "The Great Mouse Detective" -- held down the fort for family animation.

But another, more obscure animated character also made his debut that year: the playful, cantilevered desk lamp who lent his name to the short "Luxo Jr."

Some 25 years later, Fievel and Basil have faded from view.

Luxo, by contrast, appears on screen every time Pixar Animation releases another movie -- as the star of the animation juggernaut's logo.

Pixar's current computer-animated feature, "Cars 2," zoomed into theaters June 24 and -- just like the 11 Pixar releases that preceded it -- opened as the week's No. 1 movie.

Hardly a surprise, according to Lee Josselyn , vice president of operations and film buyer for the Galaxy Theatres chain, which includes the Cannery's multiplex in North Las Vegas.

"So far, Pixar hasn't had a loser," Josselyn says. "We see Pixar on our release schedules and we know we've got a guaranteed winner for that month."

Overall, "it's the greatest track record, arguably ever," says veteran box-office analyst Paul Dergarabedian of the Hollywood.com website.

Pixar's winning streak testifies to its hold on audiences -- and animation's ever-increasing box-office clout.

Last year, for example, animated features accounted for five of the year's top 10 box-office attractions.

At No. 1: Pixar's Oscar-winning "Toy Story 3," which racked up a worldwide gross of more than $1 billion. Also in the Top 10 for 2010: DreamWorks Animation's "Shrek Forever After," in fifth place with more than $752.6 million in worldwide ticket sales; Disney's "Tangled," at No. 8 with a take of more than $590.7 million; Universal's "Despicable Me," at No. 9 with more than $543.1 million; and, at No. 10, DreamWorks' "How to Train Your Dragon," with more than $494.8 million.

And the trend continues; at the start of 2011, when "the box-office was tanking," such animated features as "Rio" and "Rango" drew audiences when few other movies did, Dergarabedian points out.

"It's the fact that families need entertainment," he says.

And these days, the family audience means more than just the kids, Josselyn notes.

In the past, parents would drop their kids off to see the latest big-screen cartoons, but Pixar has raised the animation bar so high that parents watch with their kids, he says.

Or the grown-ups watch by themselves; in the case of "Toy Story" and its sequels, Josselyn adds, "I know at 10 o'clock at night, we could be selling out -- and it was all adults."

Which is precisely the point for the makers of "Toy Story" and other Pixar hits.

"In particular, we do not want to focus on children," asserts Pixar co-founder Ed Catmull , president of Pixar and Walt Disney Animation. (The studios merged when Disney bought Pixar in 2006.)

Despite Pixar's all-ages appeal, "children live in an adult world," says Catmull, a five-time Oscar-winner for his technical contributions. "If you give them something a little over their heads, they like that better, because that's reality."

Such wide appeal hearkens back to such Walt Disney-produced classics as 1938's landmark "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" -- which proved that audiences were ready for more than short cartoons and would not only watch, but be enchanted by, animated features.

Those movies and other Disney classics that followed emphasized not only artistry but technical innovation, Catmull points out.

"When Walt Disney first formed his company," he says, "filmmaking and animation was high-tech," with breakthroughs in sound and color. "That changing of technology was part of the excitement."

Pixar scored its own game-changing technological breakthrough when 1995's "Toy Story" became the company's first fully computer-animated feature, following five shorts. (Including "Luxo Jr." -- the first Pixar short produced after Apple co-founder Steve Jobs bought, spun off and renamed the computer graphics division of "Star Wars" creator George Lucas' Lucasfilm Ltd.)

Catmull, who joined Lucasfilm in 1979, says he thinks computer animation "definitely brought in something new" to the form.

"I don't think 'Toy Story' would have worked if it was hand-drawn," he says, although continued developments in computer animation mean "the first images in 'Toy Story' are a little plastic-y looking" by today's standards. (As examples, he cites the simulated ocean waves of "Cars 2" or Rapunzel's resplendent hair in Disney's "Tangled," both of which required "a massive amount of computer power" to create.)

These days, computer animators "can deal with far more complex environments" than ever before, Catmull says.

But "it's not about the technology," he insists, recalling "Toy Story's" debut -- and how "incredibly proud" the "technical people felt" because most reviews of the movie mentioned "Toy Story's" computer-animated status in passing, concentrating instead on the movie's artistry.

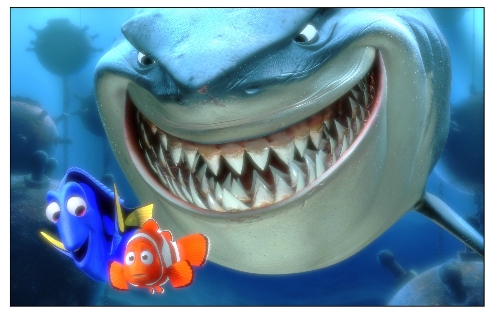

Such Pixar releases as "Finding Nemo," "The Incredibles," "Ratatouille," "WALL-E" and "Up," Oscar-winners all, "don't require the qualifier 'animated movie,' " in Dergarabedian's view. "They're just great movies," as "Snow White" and "Pinocchio" were in their day.

At Pixar, "everyone understands that making the great movie" remains the focus, Catmull says.

And the studio's subsequent success has inspired other studios to enter the computer-animation fray.

Some have been wildly successful. DreamWorks' "Shrek" quartet will become a quintet with November's "Puss in Boots" spinoff, and Fox plans a fourth "Ice Age" installment next year. But some haven't quite captured the audience's collective imagination. ("Mars Needs Moms," anyone? How about "Battle for Terra" or "Legend of the Guardians: The Owls of Ga'hoole" ?)

Such "fierce and ferocious" competition means "the people who won are the audience," Dergarabedian says.

Still, Catmull reasons, "it's not any easier to tell a story" these days, no matter how many talented computer animators turn up in Hollywood.

Which means Pixar will continue to follow its winning formula.

"Everyone says quality is the most important thing, but that isn't the way most people act," he observes. "We're trying to make films that touch world culture in a positive way."

Contact movie critic Carol Cling at ccling@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0272.