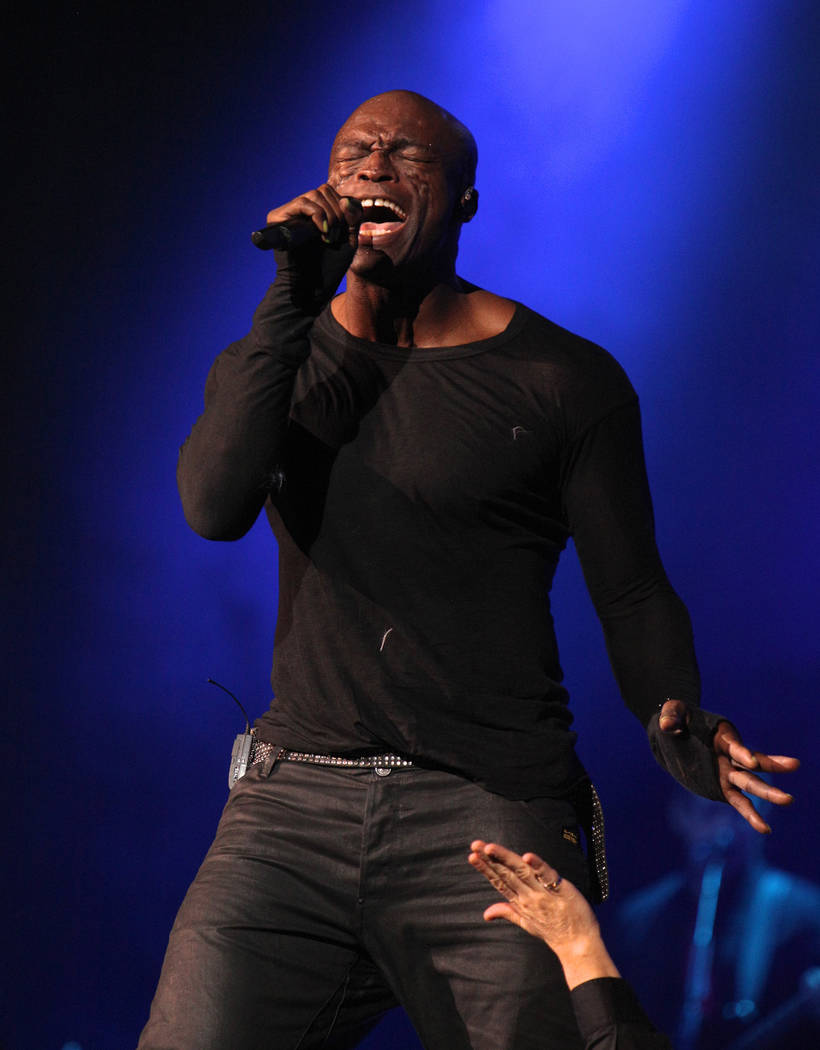

Seal weathers music industry’s winds of change

Beneath a sewing machine, a career in music was born, along with so many hairpieces.

The year was 1967, and Henry Olusegun Adeola Samuel was a boy of 4 in his native London.

As his mother worked, she listened to music.

So did Henry.

“She was a seamstress, a wigmaker,” Samuel recalls. “She’d play a lot of (Burt) Bacharach and (Hal) David, a lot of Dionne Warwick. I was introduced to a lot of Motown.”

An ear for music translated into a voice for song.

Samuel discovered this seven years later, when he would perform publicly for the first time at the behest of his primary-school teacher.

“He put me on stage to sing a Johnny Nash song called ‘I Can See Clearly Now’ at an assembly,” he recalls. “My parents had never heard me sing before. And then I got sort of this rapturous round of applause. That’s when I guess I really understood what my voice was and what my purpose was on this Earth.”

And that’s when Seal started to become Seal.

But it wasn’t an overnight thing.

‘Crazy’ success

In the late ’80s, the burgeoning singer would kick around Japan with a British funk band and join a blues group in Thailand before hooking up with DJ-producer Adamski. The two would co-write “Killer” in 1990, an acid-house smash that hit No. 1 in the U.K. and launched Seal’s career in earnest.

When Seal released his self-titled debut a year later, the first single, “Crazy,” made him a star on these shores.

With its cool-breeze vocals set atop an oscillating synth line, the song is a ’90s signature that has since been covered by everyone from Alanis Morrisette to metallers Mushroomhead to pop-punk cut-ups Me First and the Gimmes Gimmes.

Covering “Crazy” is a tricky endeavor, though, because of that voice: It’s a thing as rich in emotion as a family photo album and just as capable of distilling that emotion palpably, viscerally. Seal’s voice is earthy and ethereal at once, lithe yet sonorous, the vocal approximation of the notion of finding strength in vulnerability.

But what’s also distinguished Seal over the years is the subtle sophistication of his songbook. He’s tended to favor elegance and understatement over pop bombast, and even when he’s eyeing the dance floor, there’s an attention to detail in the mix, an emphasis on texture as much as pure, beat-driven torque.

Seal traces this back to his youth, to all those Bacharach and David numbers, as well as his love for Rat Packers Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, whose catalogs were as artfully arranged as they come.

No more albums?

Because of all this, Seal has always been an album-oriented artist, despite his share of successful singles such as the aforementioned hits and “Kiss From a Rose,” Seal’s biggest and most celebrated number, which won record of the year, song of the year and best male pop vocal performance at the 1996 Grammy Awards.

The vocalist has been vocal about how the shifting fortunes of the music industry have made it difficult for artists such as him to continue to produce full-length albums intended as singular artistic statements.

“The issue is that the market doesn’t really allow for artists to spend the money and time into making what we perceive as the concept album or just the album in general,” he says. “Music is consumed differently nowadays. We are now dealing with a situation where record companies are faced with diminished returns, so they’re not spending or certainly not investing in the infrastructure that is required for an artist to make that kind of album.

“Yes, music is still emotional and, yes, the song and the voice, those two things never change,” he continues, “but just about everything else has: the way it’s consumed, the way that it’s delivered, the way that it’s actually made, the time, or lack thereof, spent in the recording studio — all of those have changed because of a lack of money.”

Seal doesn’t blame the primary agents of these changes — iTunes at first, now Spotify — for said developments as much as the record labels he feels enabled them to become game changers.

“In the face of the evolving technology they had an opportunity to open the storefront and to own and control what became known as iTunes,” he says. “But because of their greed and inability to communicate — and unwillingness to communicate — they didn’t, and Steve Jobs came in and basically built that store under their noses and took away their business. He had different interests. He didn’t really care about the music; it was more about Apple. Spotify followed suit with that.”

On silver linings

Still, Seal is not a sky-is-falling kind of guy.

Though he hasn’t put out an album of new material since 2015’s “7” — his last record, 2017’s “Standards,” was a covers collection — and has hinted that he might not ever do so as he’s done in the past, he remains eager to perform and create, he notes.

After all, when the winds of change gust, there’s fresh air to be had.

“It’s not all doom and destruction,” he says. “Along with this kind of free-for-all, as it were, it has brought unexpected advantages and bonuses in that it’s now really easy to distribute music. At the press of a button, you can get that music to a lot more people.

“It’s a give and take,” he adds. “I think that, ultimately, more people are listening to music now. It’s up to us, the artists, to make better music. And then get it to them.”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @JasonBracelin on Twitter.