The untold story of U2’s 1987 video shoot in downtown Las Vegas

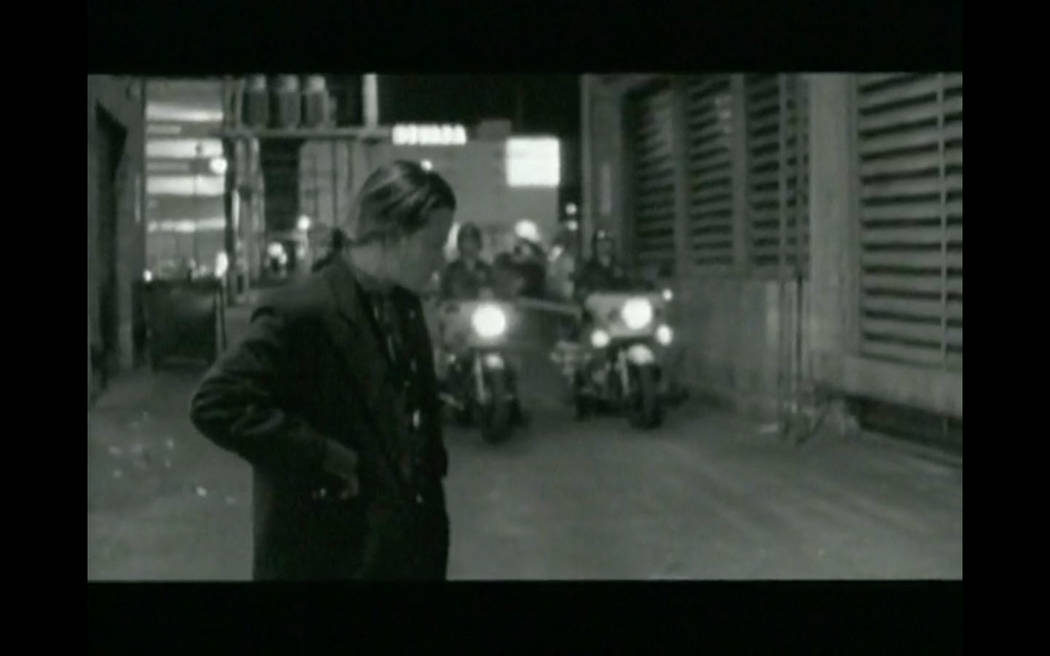

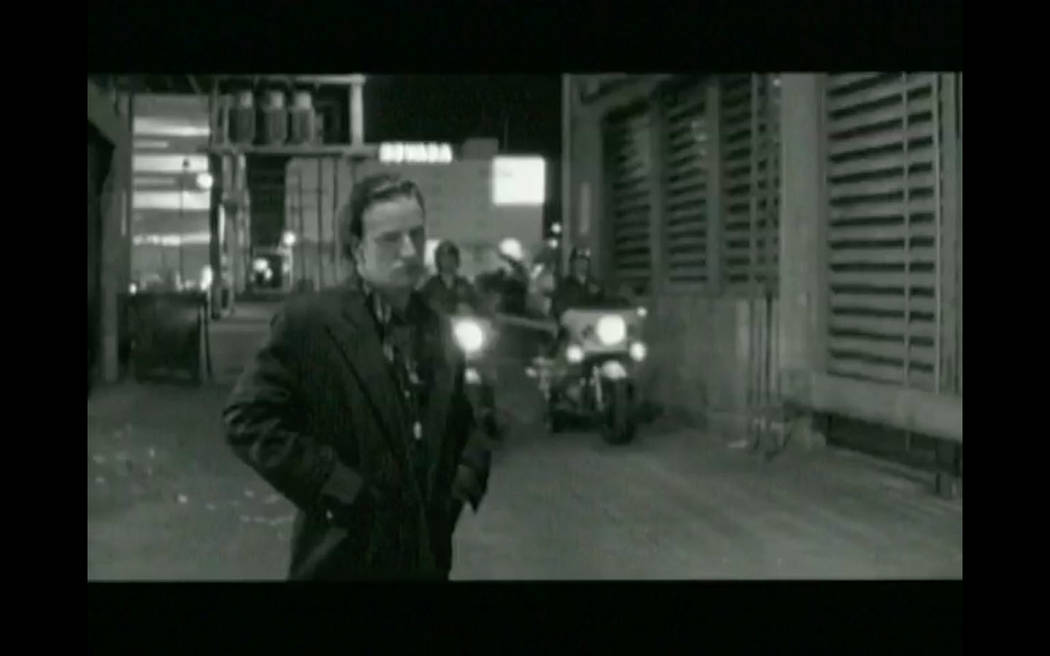

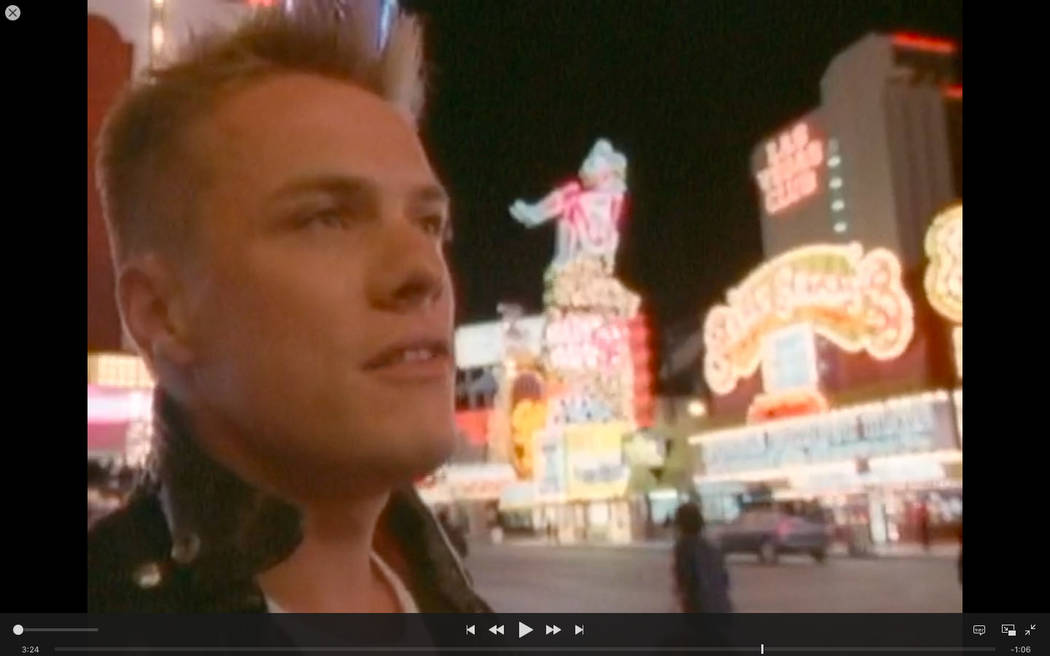

He sings of scaling the highest of mountains from the depths of downtown, his wardrobe as black as the shadowy alley down which he strolls. A flash of Las Vegas police motorcycle headlights illuminates Bono from behind as he ambles forward, his voice and arms rising in unison as a sudden burst of color swallows the darkness like neon jaws clamping shut.

The camera moves in circles and films at an exceptionally slow rate — six frames per second as opposed to the standard 24 — creating a swirl of light and sound that visually mimics what’s taking place in front of this casino or that, where any boundaries between artist and audience are being similarly blurred.

It’s April 12, 1987, and U2 is about to become the biggest band in the world.

Five days earlier, the Irish rockers’ fifth studio album, “The Joshua Tree,” hit No. 1.

It would stay there for nine weeks.

Five days earlier, the band launched what would become its transformative U.S. tour in Tempe, Arizona.

But now here they are on the streets of Vegas shortly after playing their first local show at the Thomas & Mack Center, their frontman kissing strangers, clambering atop the hood of sports cars idling at stoplights, slapping low-fives to saucer-eyed kids out past their bedtime.

His band mates are alternately stoned-faced and bemused as they take part in the video shoot for “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For,” which would become one of their most iconic clips. The video was an instant sensation, nominated for four MTV video music awards the following year, showcasing not just the band, but downtown Vegas to the world.

“In those days, that video went their version of viral, and that’s what put the downtown area back on the map, absolutely,” says Fremont Street Experience President and CEO Patrick Hughes, a Dublin, Ireland, native who credits the clip with making him dream of living in Vegas someday. “I fell into the casino industry in ’88 and traveled around the world with the intent of coming here because of that video. It showed the freedom of this country.”

On the eve of the 30th anniversary of the shooting of the video, it remains an enduring snapshot of a band, of a part of Vegas, that would soon be changed irrevocably.Binions

And it was all done in one take, shot in less than three hours with a skeleton crew and an unsuspecting cast of extras, some seated at slot machines, others just passing by.

Nothing was rehearsed; every interaction was spontaneous.

“All the stuff that happened in the video,” director Barry Devlin recalls, “really happened.”

The concept

It’s one of the band’s most deeply felt songs, as vulnerable as it is stirring, a search for that elusive, missing piece in a jigsaw puzzle of longing and desire.

“ ‘I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For’ is a very open confession of the way somebody feels about how his life is going,” Devlin says from his native Dublin, Ireland. “And I thought, ‘OK, well let’s shoot the most sincere song they’ve ever written in the least sincere city they’ve ever played.’ There was an ironic counterpoint to the song, in a way, by shooting it in Vegas.”

That Devlin even got the opportunity to make the video was the result of a bit of good timing: A longtime associate of the band who recorded their first demo in the late ’70s, he was on the road with the group to film a documentary on what would later prove to be U2’s breakthrough U.S. tour.

Initially, there were no plans to even make a clip for the song in question.

“This was just a side assignment that kind of came up last minute because they were under pressure to deliver a video, so we said, ‘OK, we’ll do that,’ ” says Declan Quinn, the cinematographer for said documentary, whose credits also include such well-received films as “Leaving Las Vegas,” “In America” and “Rachel Getting Married.” “We kind of innocently didn’t get involved in the normal pre-production and planning that would go into a making a video for a big band.”

As such, they had little money for the production and even less time to shoot it.

This is where Vegas came in: In addition to the obvious thematic hook of filming a video about searching for something to fill a void inside oneself in a city where thousands come to do just that, Vegas itself served as a natural back lot for a cash-strapped shoot.

“I only had two lights, really,” Devlin recalls of his limited equipment, “but Las Vegas has the biggest lighting budget in the entire world.”

And so Devlin persuaded the band to give him some time after their Thomas & Mack gig, but there was just one problem: getting the group from the venue to downtown without thousands of fans flocking along and disrupting the shoot.

“If the audience knew that we were filming on Fremont Street, we would have been overwhelmed,” Devlin says. “I was a big fan of the Beatles, and I’d watched a ‘Hard Day’s Night,’ so I did something I always wanted to do: I got four look-alikes dressed up like the guys to go home in the limousines, and the crowd followed them. Then the band came down to Fremont Street in a laundry van.”Fremont

Some of U2’s handlers were less than thrilled at this arrangement.

“When the band jumped out of the laundry van, (then-U2 manager) Paul McGuinness arrived and went, ‘This shoot’s off. This is kind of mad,’ ” Devlin says. “And I went, ‘Oh, Paul, this is kind of my dream.’ He went, ‘OK, 2½ hours.’ ”

The shoot

The sound system was pushed around in a shopping cart borrowed from a homeless man.

A wheelchair was used for the Steadycam shots.

The sidewalk doubled as a stage.

“It was so low-tech,” Devlin says of the shoot. “But that meant we could get in right close. We were walking around people, we were close up to people’s faces, we could get into doorways.”

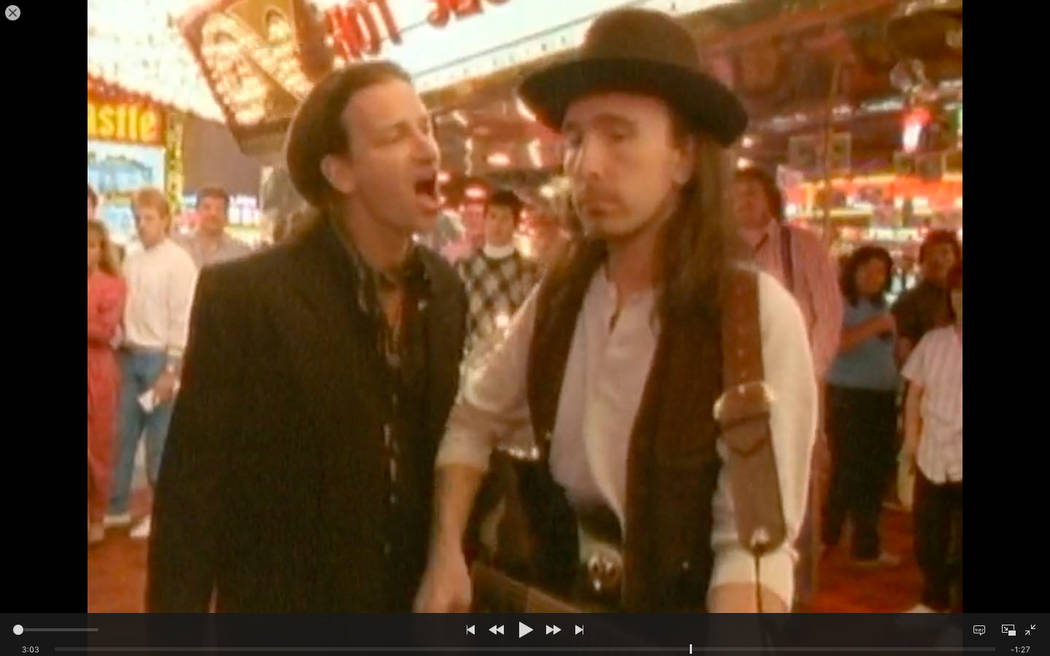

Devlin mostly just sought to capture the band members being themselves, but for the interactions between Bono and The Edge, he instructed the former to carry himself like an overaggressive street preacher pestering the latter as if brimstone showers were in the forecast.

“I said, ‘Edge, you’re a guy who’s trying to make a living busking, there’s this mad guy who keeps wanting to tell you about God, and what you’re trying to do is just get away from him,’ ” Devlin says. “And that’s how they played it. It’s really quite funny, The Edge trying to ignore this lunatic on his shoulder and Bono keeping after him.”

What really makes the video, though, is Bono’s encounters with various onlookers, smooching strangers, diving into people’s arms, peacocking merrily among various casino workers.

“All those interactions were real,” Devlin says. “In an odd way, people kind of loved hugging him and vibing with him, but they weren’t necessarily fans. They were guys and girls on the street, they were working people in clubs, whereas if you had his adoring fans there, it would have been quite different and too sycophantic.”

At this time, U2 still considered itself to be a band of the people, not long removed from playing small halls and clubs, and Bono, in particular, seemed to be in his element cavorting with various faces in the crowd.

“I think he really loved being in public performing this song,” Quinn recalls. “He was a little bit chuffed at the whole thing, but he really pushed through whatever inhibitions he had and made a beautiful, natural performance where he’s slightly vulnerable and slightly evangelical.”

As for drummer Larry Mullen Jr. and bassist Adam Clayton, well, that was a different story.

“The other guys were embarrassed,” Quinn says. “Larry was like, ‘I don’t even have a drum, what am I supposed to do? Hit the sign post with drumsticks or something?’ I remember Adam kind of going, ‘OK, that’s enough, you got one chorus out of me, I’m getting in a taxi,’ and he just took off.”

And that was pretty much the end of the shoot.Cowgirl

“Afterwards, Bono said to me, ‘Hey, I kissed a lot of people I never met before, didn’t I? Do you think that was wise?’ And

I went, ‘I think it was really the least-wise thing you’ve ever done,” Devlin chuckles. “ ‘But I wouldn’t regret it.’”

The aftermath

U2’s name was in flames, the heat of the band’s burgeoning celebrity practically singeing the pages of the publication heralding its stardom.

Fifteen days after the video shoot, U2 found itself on the cover of Time magazine, the band’s logo emblazoned in fire above a headline branding it “Rock’s hottest ticket.”

When U2 arrived on these shores to kick off “The Joshua Tree” tour, it was already big enough to play arenas, if not always fill them.

To wit: the Vegas gig was far from capacity.

“Our show sold less than 9,000 seats,” says Pat Christenson, president of Las Vegas Events, who booked the concert. “The whole U2 phenomenon happened a couple months later.”

But a cloudburst of notoriety was fast approaching.

The band knew it was on its way, could see it like an oncoming storm front, darkening the horizon.

This palpably informs the anxious, bustling feel of the “Still” video.

“There’s a breathlessness about it, and there’s a breathlessness of guys trying to catch up to their own lives,” Devlin says. “It’s very difficult to say what it was like between the time when they hit America to the point where Time was saying, ‘Biggest band in the world.’ That was six weeks.”

The night of April 12, then, served as maybe the final glimpse of a band soon to be thrust into the maw of fame.

There would be no return

“You can’t plan for a band being absolutely on the cusp and being willing — for probably the last time — to be entirely honest and let themselves be caught on camera in the way that they were,” Devlin says. “I don’t think U2 would have ever let themselves do that again.”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @JasonBracelin on Twitter.

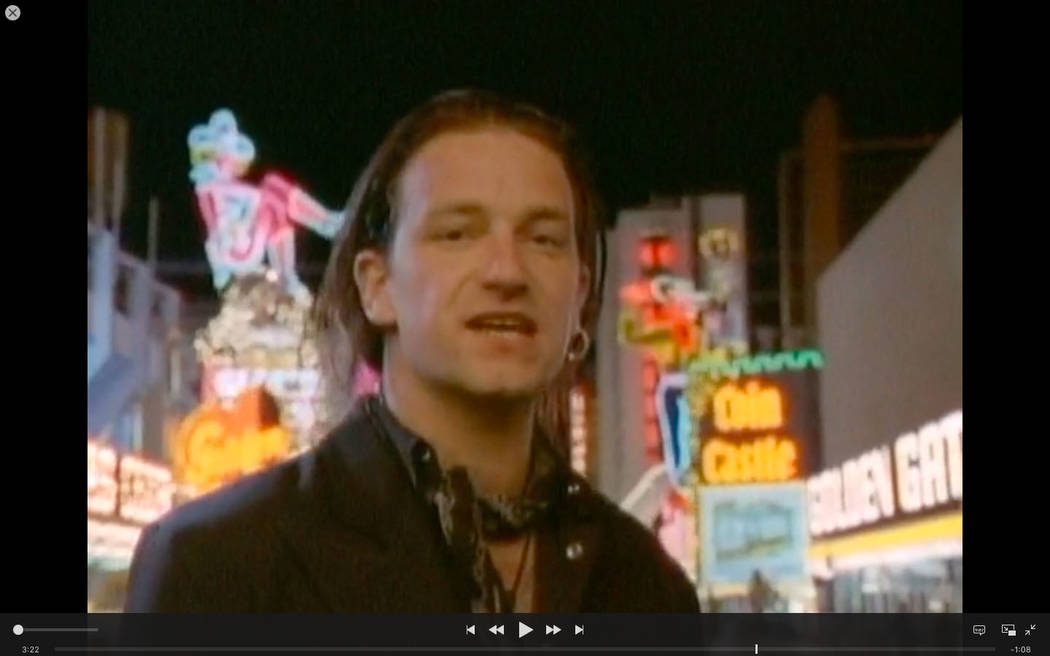

Fremont Street, then and now

— There was no canopy above Fremont Street

— Car traffic was still allowed on Fremont Street between Main Street and Las Vegas Boulevard

— The Mint Casino would be incorporated into Binion's

— The Coin Castle and Pioneer Casino, both seen in the video, have been closed

— Vegas Vicki, the neon showgirl sign, no longer sits above the now-shuttered Glitter Gulch